The Violence of 'Conservation'

In a leaked report revealed to The Guardian in February, an investigation by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) found that armed eco-guards, partly-funded by the WWF to protect wildlife in the Republic of Congo, subjected Baka tribespeople to violent abuse and human rights violations.

The conservation giant has been trying to create a protected zone around Messok Dja, a huge forested area rich in wildlife and biodiversity, where the Baka people have lived for generations. UNDP investigators found that the Baka were not consulted about the project and suffered extreme violence at the hands of eco-guards, who also exclude them from the forests they depend on for food and medicines to survive.

Along with WWF, as well as palm oil and logging conglomerates, UNDP is a sponsor of the $21.4 million conservation project. A sizeable chunk of this funding goes to ‘conservation’ in Messok Dja, where the rest is allocated to TRIDOM, another forest situated across Cameroon, the Republic of Congo and Gabon. Under pressure from activists, the UNDP launched an investigation after receiving letters from the Baka in 2018 and complaints from Survival International (SI).

One letter, signed by Baka people in Mbaye village, said: ‘They ban us from going to the forest. If we make camps in the forest the eco-guards burn them down. Many Baka are dead today. Children are getting thinner. We are already finished off with the lack of forest medicines. We tried to tell our difficulties to the WWF but they do not accept them. They just tell us we cannot go to the forest.’

A draft report of the investigation, dated 6 January 2020, includes damning testimony of eco-guards beating Baka men, women and children. Other reports refer to eco-guards forcing Baka to beat each other at gun point; guards taking away machetes then using them for beatings; and eco-guards forcing Baka women to take off their clothes ‘to be like naked children’.

The draft report adds, ‘The violence and threats are leading to trauma and suffering in the Baka communities. It is also preventing the Baka from pursuing their customary livelihoods, which in turn is contributing to their further marginalisation and impoverishment.’

Unfortunately, this is only the tip of the iceberg. Just as shocking as these most recent revelations is how long WWF have known about this and done so little to put it right, and how until now, their conduct has been ignored by international bodies like the UN.

‘[Eco-guards] see Baka as animals, they don’t see us as humans,’ a Baka man from the Congo Basin told an SI researcher.

Liquid error: internal

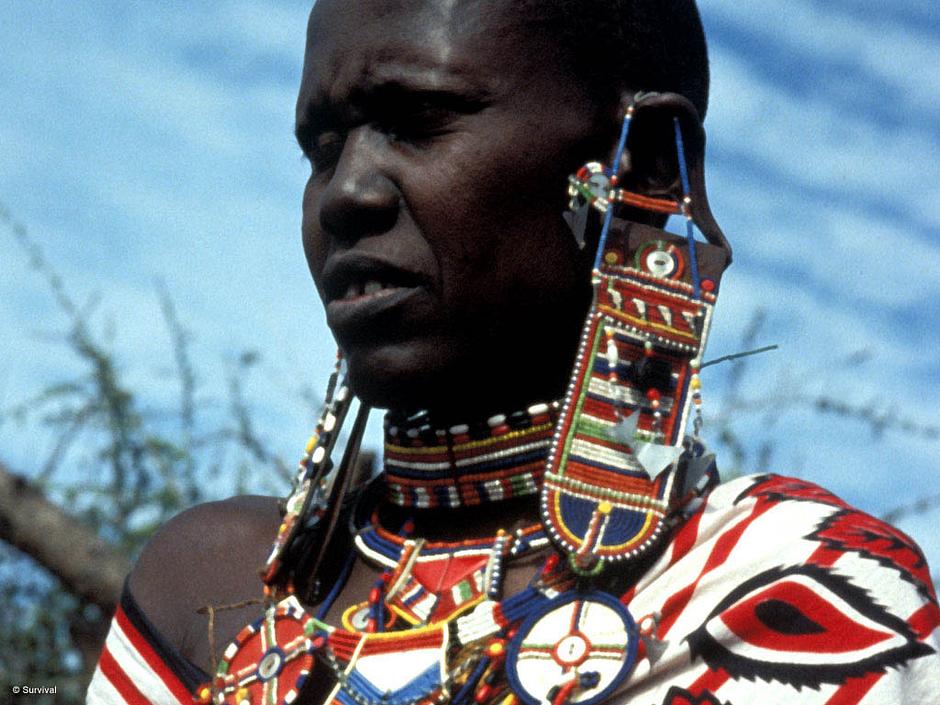

International and the Indigenous and tribal people it partners, have been campaigning since the 1980s against atrocities committed in the name of conservation. Agents supported by world-renowned nature groups, national governments and international bodies have tortured and murdered dozens of innocent and vulnerable people. Park rangers and government officials have burned down villages, bulldozed houses, gang-raped women, stolen possessions, beaten people up and maimed them for life.

Vast areas of land have been stolen from tribal people and local communities under the false claim that this is necessary for conservation. The stolen land is then called a ‘protected area’ or ‘national park’, and the original inhabitants are kept out; sometimes with the kind of violence that has been inflicted on the Baka.

Cultural Imperialism

First created in the United States in the 19th century, national parks were predicated on the notion that nature is ‘untouched wilderness’ until white people ‘discovered’ it. According to Chief Luther Standing Bear of the Sicangu and Oglala Lakota: ‘Only to the white man was nature a “wilderness” and only to him was it “infested” with “wild” animals and “savage” people. To us it was tame.’

Thousands of Native American people were not ‘just’ living on the land, but actively using, shaping and nurturing it. They were playing a vital part in these ecosystems and possessed deep understanding of them, yet were perceived as no more than an ‘inconvenience’ to be ‘dealt with’, just like the inhabitants of African and Asian protected areas are today.

The tragic irony is that mass tourism, trophy hunting and ‘sustainable’ logging, mining or other resource extraction are often welcomed in areas where the original inhabitants have been evicted and forbidden from using the land themselves.

Both in 19th century North America and in much of Africa and Asia today, ‘conservation’ has meant that the original custodians cannot live on their ancestral lands, but tourists can come there on holiday; local people are forbidden from hunting for food in places where foreigners hunt for sport and Indigenous communities are banned from using resources they depend on to survive. The definition of ‘sustainable’ here is conveniently bent to permit logging concessions and industrial mining on ‘protected’ land.

The idea that Indigenous peoples don’t understand how to care for their environment stems from cultural imperialism. Evidence from across the world shows that securing land rights for Indigenous communities produces comparable or even better conservation outcomes at a fraction of the cost of conventional conservation programmes.

United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz said in a 2018 report: ‘When bulldozers or park rangers force Indigenous peoples from their homes, it is not only a human rights crisis, it is also a detriment to all humanity. Indigenous peoples… are achieving at least equal conservation results with a fraction of the budget of protected areas, making investment in Indigenous peoples themselves the most efficient means of protecting forests.’

Anyone who truly cares about the planet must stop supporting forms of ‘conservation’ that wound, alienate and destroy Indigenous and tribal peoples. It’s time for conservation to recognize them as senior partners in the fight to protect their own land: for their tribes, for nature and for all humanity.

3 March 2020