The Sentinelese are an uncontacted Indigenous people living on North Sentinel Island, one of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Indian Ocean. They vigorously reject all contact with outsiders.

Survival International lobbies, protests and uses public pressure to ensure their wish to remain uncontacted is respected.

If not, the entire people could be wiped out by diseases to which they have no immunity.

Most isolated people

The Sentinelese are the most isolated Indigenous people in the world. They live on their own small forested island called North Sentinel, which is approximately the size of Manhattan, and which is part of an island chain that is also home to another uncontacted people, the Shompen. They continue to resist all contact with outsiders, attacking anyone who comes near. See Survival’s wider campaigns for uncontacted peoples here.

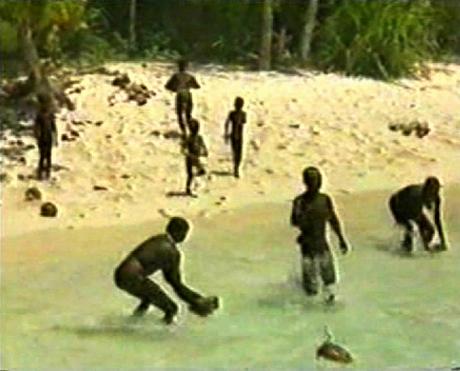

© Indian Coastguard/Survival

© Indian Coastguard/Survival

In March 2025, American social media influencer Mykhailo Viktorovych Polyakov illegally landed on the island for a few minutes in an attempt to contact the Sentinelese. He didn't see any people but left a can of cola and a coconut as "offerings". He was then arrested by the Indian authorities and could face a jail sentence. In a reckless attempt to get attention on social media, his illegal actions could have wiped out the entire Sentinelese tribe through introducing new diseases such as flu to which they have no immunity.

His actions are reminiscent of John Allen Chau, an American missionary who illegally landed on the island in 2018 and was killed by Sentinelese people while trying to convert them to Christianity. Similarly, in 2006, two Indian fishermen, Sunder Raj and Pandit Tiwari, who had illegally moored their boat near North Sentinel to sleep after poaching in the waters around the island, were killed when their boat broke loose and drifted onto the shore. Poachers are known to fish illegally in the waters around the island, catching turtles and diving for lobsters and sea cucumbers.

The Sentinelese have made it clear that they do not want contact. It is a wise choice. Neighbouring Indigenous peoples were wiped out through disease and violence after the British colonized their islands

How the Sentinelese live

Most of what is known about the Sentinelese has been gathered by viewing them from boats moored more than an arrows distance from the shore and a few brief periods in the past where the Sentinelese allowed the authorities to get close enough to hand over some coconuts. Even what they call themselves or their island is unknown, though the neighbouring Onge people call North Sentinel 'Chia daaKwokweyeh'.

The Sentinelese hunt and gather in the rainforest, and fish in the coastal waters. Unlike the neighboring Ang people, they make boats - very narrow outrigger canoes. These can only be used in shallow waters as they are steered and propelled with a pole like a punt. The fact that the island has remained fully covered in rainforest is more evidence that Indigenous peoples’ are the world’s best conservationists.

They are a nomadic, hunter gatherer people and it is thought that the Sentinelese live in three groups, with an estimated total population of anywhere from 50 to 150 people. They have two different types of houses; large communal huts with several hearths for a number of families, and more temporary shelters, with no sides, which can sometimes be seen on the beach, with space for one family unit. The women wear fibre strings tied around their waists, necks and heads. The men also wear necklaces and headbands, but with a thicker waist belt. They carry spears, bows and arrows.

© A. Justin, An. S.I.

© A. Justin, An. S.I.

Although commonly described in the media as ‘Stone Age’ or 'Pre Neolithic', this is clearly not true. There is no reason to believe the Sentinelese have been living in the same way for the tens of thousands of years Indigenous peoples are likely to have been in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Their ways of life will have changed and adapted many times, like all peoples. For instance, they now use metal which has been washed up or which they have recovered from shipwrecks on the island reefs. The iron is sharpened and used to tip their arrows.

From what can be seen from a distance, the Sentinelese are clearly extremely healthy and thriving, in contrast to the Great Andamanese and Onge peoples to whom British colonial officials attempted to bring ‘civilization’. The people who are seen on the shores of North Sentinel look proud, strong and healthy and at any one time observers have noted many children and pregnant women.

They attracted international attention in the wake of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, when a Sentinelese man was photographed on a beach, firing arrows at a helicopter which was checking on their welfare.

© Christian Caron – Creative Commons A-NC-SA

© Christian Caron – Creative Commons A-NC-SA

Harrowing attempts at contact

In the late 1800s M.V. Portman, the British ‘Officer in Charge of the Andamanese’ landed, with a large team, on North Sentinel Island in the hope of contacting the Sentinelese. The party included officers, convicts, and other Andamanese people who had already been forcibly contacted by the British.

The party found recently abandoned camps and paths but the Sentinelese were nowhere to be seen, though they did find the skeleton of an old man “placed in a large bucket, in a sitting posture, and hidden in the buttressed roots of a big tree”. It’s possible that the Sentinelese honour their dead in this way. After a few days, the party saw an elderly couple and four children who, "in the interest of science" were kidnapped and taken to Portman's house in Port Blair, the regional capital. Predictably they soon fell ill and the adults died. The children were taken back to their island with a number of gifts.

It is not known how many Sentinelese became ill as a result of this ‘science’ but it’s likely that the children would have passed on their diseases and the results would have been devastating. Intergenerational trauma from this harrowing experience and other similar ones is likely to account for the Sentinelese’s determination to avoid contact with outsiders.

Portman himself would later reflect:

Contact rejected

During the 1970s the Indian authorities made occasional trips to North Sentinel in an attempt to befriend the Sentinelese. These were often at the behest of dignitaries who wanted an adventure. On one of these trips, a pigs and a doll were left on the beach. The Sentinelese speared the pigs and buried it, along with the doll. Such visits became more regular in the 1980s; the teams would try to land, at a place out of the reach of arrows, and leave gifts such as coconuts, bananas and bits of iron. Sometimes the Sentinelese appeared to make friendly gestures; at others they would take the gifts into the forest and then fire arrows at the contact party. © Survival

© Survival

In 1991 there appeared to be a change. When the officials arrived at North Sentinel, the Sentinelese gestured for them to bring gifts and then, for the first time, approached without their weapons. They even waded into the sea towards the boat to collect more coconuts. However, friendly interactions were not to last. Although gift dropping trips continued for some years, encounters were often violent and always highly dangerous for all concerned. At times the Sentinelese aimed their arrows at the contact team, and once they attacked a wooden boat with their adzes (a stone axe for cutting wood). No one knows why the Sentinelese first dropped, and then resumed their hostility to the contact missions, nor if any of them died as a result of diseases caught during these visits.

In 1996, the regular gift dropping missions stopped. Many officials were beginning to question the idea of attempting to contact a people who were healthy and content and who had thrived without contact with outsiders for perhaps tens of thousands of years. Contact had a devastating impact on the neighbouring Onge and Great Andamanese peoples, their population falling 85% and 99% respectively. Meanwhile, the neighboring Jangil people were completely annihilated. Sustained contact with the Sentinelese would certainly have similarly terrible consequences.

In the following years only occasional visits were made, again with a mixed response. After the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, officials made visits to check, from a distance, that the Sentinelese seemed healthy and were not suffering in any way.

Following a campaign by Survival and local organizations, the Indian government finally abandoned all plans to contact the Sentinelese, and their current position is still that no further attempts to contact them will be made.

All visits to North Sentinel are now strictly illegal and the Indian Navy and coast guard patrols around a buffer zone around the island to prevent outsiders from coming too close.

A “corporate John Allen Chau project” on Great Nicobar?

The Sentinelese are the most isolated Indigenous people on Earth but their distant neighbors, the Shompen, are also among the most isolated. Living only on the island of Great Nicobar in the southernmost part of the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago, most Shompen also reject all contact with outsiders. © Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways

© Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways

While the Indian government rightly bans all outsiders from visiting North Sentinel Island, their plans for Great Nicobar Island could not be more different, as they plan to turn the island into the “Hong Kong of India.”

Over three million trees are to be felled for this “mega-development” project, to be replaced by a mega-port; a new city; an international airport; a power station; a defence base; an industrial park; and 650,000 settlers – a population increase of nearly 8,000%.

The dangers this project poses to the Shompen are enormous. In forcing contact, expressly encouraging hundreds of thousands of tourists and risking the genocide of an uncontacted Indigenous people, this project is effectively a ‘corporate John Allen Chau’ on a massive scale. The government would never dare to build such a mega-project on the territory of the Sentinelese as they know there would be a public outcry.

In February 2024, 39 international genocide experts wrote to the Indian President describing the scheme as a "death sentence." Survival joins them in calling on the Indian government to scrap this highly destructive project.

Act now to support the Sentinelese

Join the mailing list

There are more than 476 million Indigenous people living in more than 90 countries around the world. To Indigenous peoples, land is life. Find out more about them and the struggles they’re facing: sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.

News from the Sentinelese

Attempted contact with the Sentinelese tribe: Survival International response

A US national has been arrested after trying to make contact with the uncontacted Sentinelese people.

Missionary claims that John Chau did not pose a threat to the Sentinelese - Survival responds

John Allen Chau's mission could have wiped out the Sentinelese people

Survival International urges “no recovery” of body in Sentinelese case

Survival urges that no attempt be made to recover John Allen Chau's body from N Sentinel Island

Survival International statement on killing of American man John Allen Chau by Sentinelese tribe, Andaman Islands

An American has been killed by the Sentinelese tribe in the Andaman Islands, India. Survival International Director Stephen Corry responds.

Serial poacher’s arrest exposes failure to protect world’s most isolated tribe

Poaching threat raises concerns over failure to protect land of Sentinelese and other isolated Andaman tribes

Illegal fishermen encroach on world's most isolated tribe

Burmese fishermen were apprehended by the Indian Coast Guard near North Sentinel Island earlier this month