Success!

This webpage was launched in April 2012 for Survival’s global campaign to save the Awá. Two years later, in April 2014, Survival, the Awá and their supporters celebrated as the campaign scored an unprecedented victory when the Brazilian government sent in troops to expel the illegal loggers from Awá land.

Latest Awá news

July 22, 2019

August 15, 2018

November 3, 2017

October 26, 2017

In the press

Vanity Fair • Sunday Times Magazine • BBC News • Associated Press • The Atlantic • Live Science • Huffington Post • Deutsche Welle

‘In the city, we feel the same insecurity that outsiders do in the forest,’

says an Awá man named Blade. But the dense Amazon forests that used to clothe vast areas of northeast Brazil have all but disappeared. Not to be replaced by cities, but by a wasteland of seemingly endless cattle ranches. The last stand of these once great forests, some of the most ancient in all the world, are where Indigenous peoples have resisted the ranchers’ and loggers’ advances.This is the story of one tribe, the Awá hunter-gatherers, and their extraordinary love affair with the forest. A story of resistance, destruction, of hope, and, perhaps, survival.

Hunting is at the forefront of

most Awá’s minds.

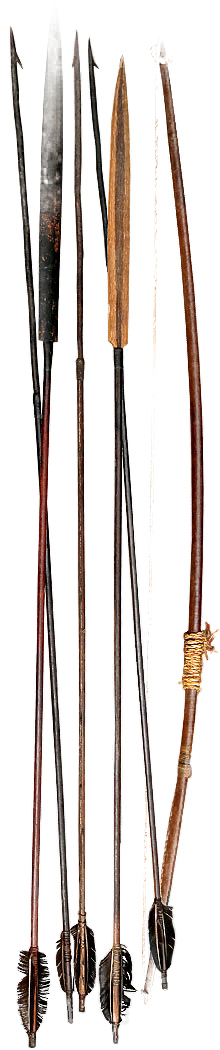

‘If my children are hungry, I just go into the forest and I can find them food,’ says Peccary Awá. Women encourage their husbands to return with plentiful game meat, and the men oblige. Those Awá still living uncontacted in the forest hunt with 2 metre (6 foot) long bows. Arrows fly high and silent into the forest canopy, allowing several shots before game is alerted to the hunters’ presence.

Some settled Awá have confiscated shotguns from poachers and have become skilled marksmen. But each hunter maintains a highly crafted bow and set of arrows for when the ammunition runs out.

Forbidden food

The forest provides its bounty, but not everything is taken. Some animals, such as the capybara and the harpy eagle, are taboo and no Awá will eat them. Eating a bat is said to cause a headache. The large opossum? Bad-smelling. Hummingbirds? Just too small. Other animals are hunted only at certain times of the year. In this way the Awá ensure the survival of the entire forest, themselves included.

Hunters vs. farmers

The Awá know their forests intimately. Every valley, stream and trail is inscribed on their mental map. They know where to find the best honey, which of the great trees of the forest are coming into fruit, and when the game is ready to be hunted. To them, the forest is perfection: they cannot dream of it being developed or improved upon.

As nomadic hunter-gatherers, the Awá are always on the move. But not aimlessly wandering, for it is precisely their nomadic way of life which nurtures a fundamental bond with their lands. They cannot conceive of moving on, of leaving the place of their ancestors.

‘The outsiders are coming, and it’s like our forest is being eaten up,’ says Takia Awá. For the outsiders—for us—staying still is falling behind.

The frontier is always moving, driven by restless Westernized societies who must keep pushing into new lands simply to maintain their way of living.

Another kind of nomadism, perhaps.

Boom, bust.

Brazil’s spectacular seams of underground resources have helped fuel its economic miracle. Seven billion tonnes of iron ore lie beneath the Carajás mine alone, 600 km (370 miles) to the west of Awá territory. It is the largest iron ore mine on the planet. Trains stretching over 2 km (1¼ miles), some of the longest in the world, run all day and all night between the mine and the Atlantic Ocean. On their way they pass just metres from the forests where uncontacted Awá still live.

When the 900 km (550 mile) long railway was built in the 1980s, the authorities decided to contact and settle many of the Awá whose lands it cut through. Disaster soon followed in the shape of malaria and flu: of the 91 people in one community, just 25 were alive four years later.

Today, the railway brings outsiders hungry for land, work and the game animals that are easily poached from the tribe’s land.

But the encroaching settlers need not spell the end for the Awá. Other tribes in Brazil, such as the Yanomami, have suffered devastating invasions. They recovered when the government was pressed to take action to protect their lands.

Family

‘Dove!’ an Awá woman named Parakeet said. ’Let’s call her Dove Awá – doves sing and walk on the ground.’

The Awá wait to choose their children’s names until they reach an age when the right name presents itself. Another of Parakeet’s daughters is called Forest Tree. One particularly wriggly child was named Earthworm.

The tribe are extraordinary pet keepers: most families have many more pets than people, from raccoon-like coatis to wild pigs and king vultures. But without question, monkeys are the Awá’s favourites.

Meet the pets

Parakeet

Parakeets are beautiful but have ear-splitting cries. The Awá share fruit from the forest with them.

Capuchin

Capuchin monkeys are one of the most mischievous pets, and are always playing tricks on their owners.

Agouti

Agoutis are the only animals that can open the hard outer shell of the Brazil nut fruit. But their incredible bite doesn't stop Awá women from breastfeeding the young animals.

Owl

These night-time creatures watch over the Awá as they tread through the forest, their path lit by the light of burning tree resin.

Peccary

Peccaries are cuddly as babies, but grow up to be huge and powerful adults — with sharp tusks.

Coati

Coatis are relatives of the raccoon. They are expert climbers and love to share a hammock with humans.

Tamarin

Tamarins love playing with Awá children. Little Butterfly, an Awá girl, has a pet tamarin, and they often tease each other.

Entering the

spirit world

You might imagine that a ritual held in the forest on the night of a full moon would feel sinister. Not the Awá’s journey to the realm of the forest spirits: this is a family affair. As wives decorate husbands with feathers from the king vulture, using tree resin as glue, young children look on.

Later, as the grown-ups’ chanting grows louder, and the men make their way to the place of the spirits, babies fall asleep in the moonlight. No drugs or alcohol are involved: chanting alone sends the men into state of trance.

You might imagine that a ritual held in the forest on the night of a full moon would feel sinister. Not the Awá’s journey to the realm of the forest spirits: this is a family affair. As wives decorate husbands with feathers from the king vulture, using tree resin as glue, young children look on.

Later, as the grown-ups’ chanting grows louder, and the men make their way to the place of the spirits, babies fall asleep in the moonlight. No drugs or alcohol are involved: chanting alone sends the men into state of trance.

Doorway to another world

During the ritual, the men leave the Earth behind as they travel to the iwa, the domain of the forest spirits. They reach this place through a doorway that takes the form of a hunting shelter, a portal between worlds. The men take turns to enter, and as they reach the iwa they encounter the souls of their ancestors and the spirits of the forest.

The hunting is always good in the iwa, for it is also home to the animals of the forest. Absent, however, are settlers—and the horses, cattle and chickens they have introduced.

Uncontacted Awá

The Awá who live without any contact with outsiders are some of the last uncontacted people on the planet.

As nomads, they carry the things they need with them as they move: bows and arrows, children, pets. Everything comes from the forest: the baskets made from palm leaves, the loops of vine used to climb trees, and the tree resin burned to provide light.

Wamaxua Awá, one of the most recently contacted people in the world, talks of life before and after contact.

Worldly possessions of a nomadic hunter

Makỹa

Loops of vines allow the Awá to climb the forest's tallest trees in search of honey.

Manakũa

After a successful hunt, the Awá quickly make rucksacks from woven palm leaves.

Irapara, iwya

2 metre (6 foot) long arrows fly high into the forest canopy, guided by fletchings crafted from harpy eagle feathers.

Ikaha

These strong hammocks are made from the fibres of palm trees.

Tapãí

The nomadic Awá who still live uncontacted in the forest don't build houses, but construct shelters from branches and palm leaves.

The most vulnerable tribe on Earth

Despite their extreme self-sufficiency, the uncontacted people are also uniquely vulnerable. The common cold could kill an entire group, and, if they run into illegal loggers, their bows and arrows will be no match for the invaders' guns.

INVASION

Uncontacted Awá are always moving between hunting grounds. But now they have another reason to keep moving.

It’s not just the Awá who appreciate the forest’s giant trees: their territory is legally protected, but criminal logging gangs make big money here. Only the tribe’s resistance and the onset of the rainy season slows their advance; the government is barely present at the frontier.

Time to act, none to waste

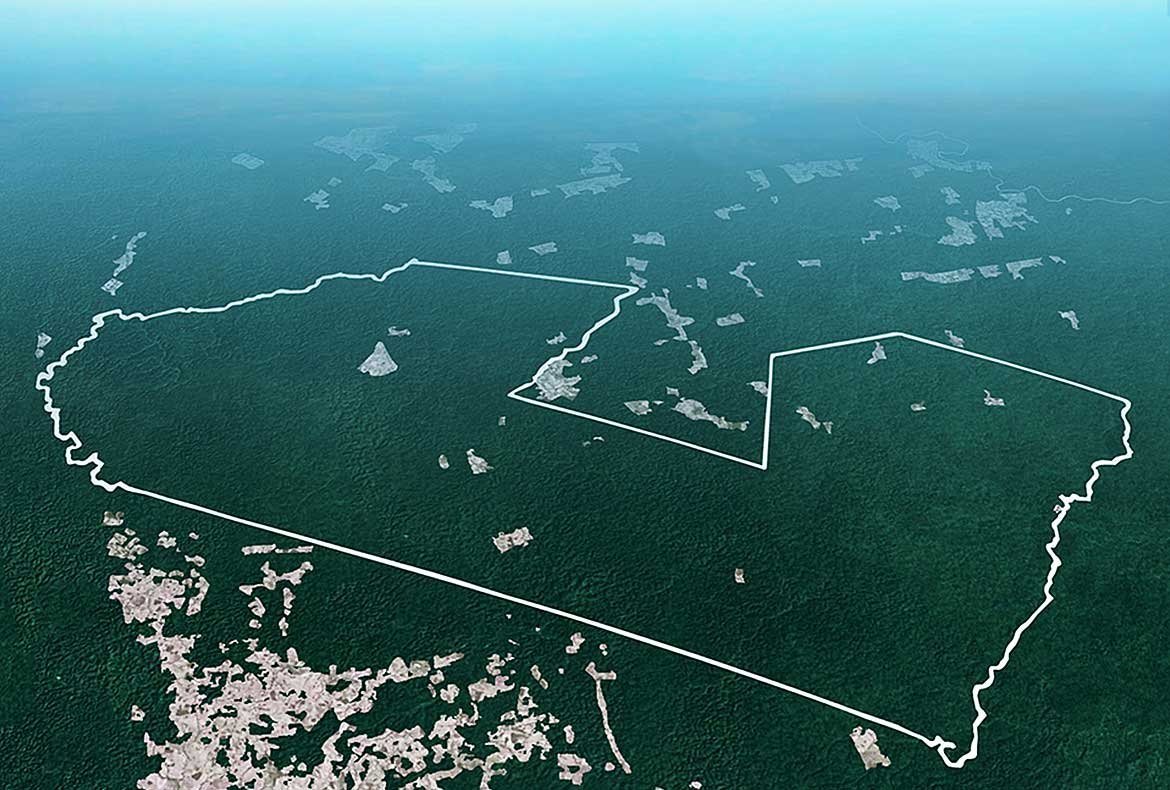

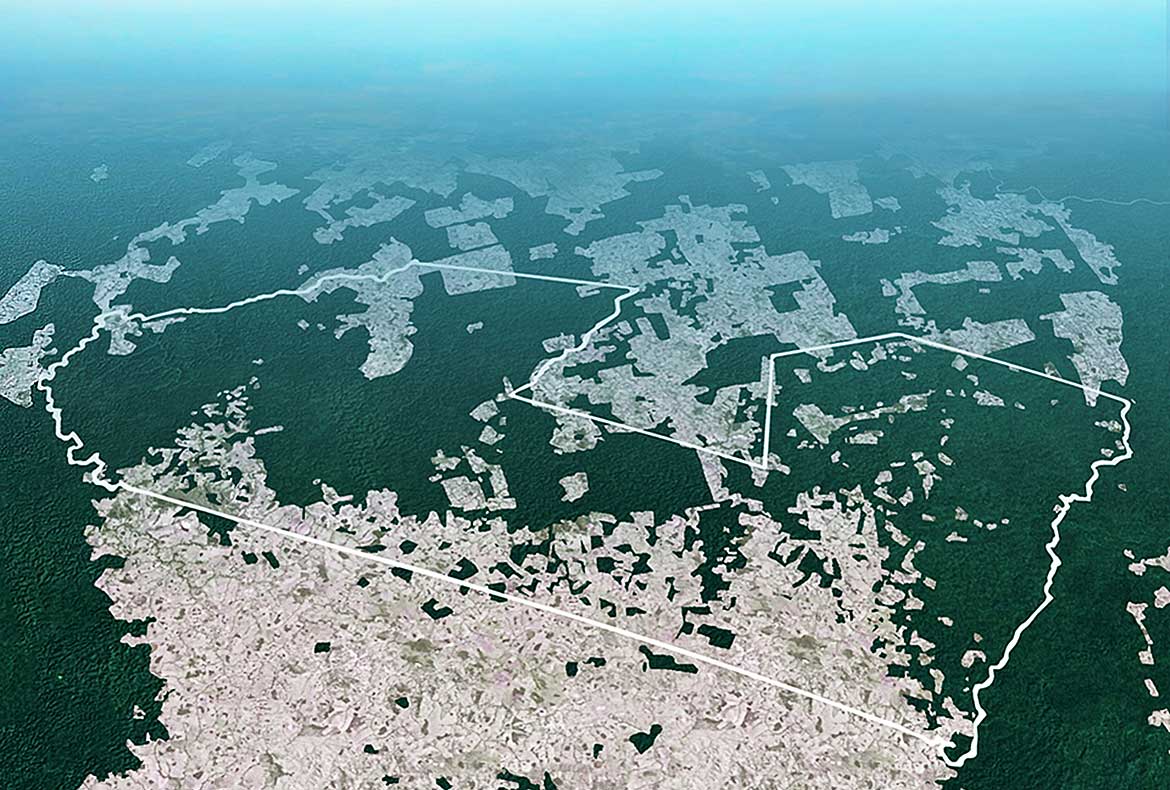

The work of the loggers and ranchers has reached crisis point: over 34% of one legally-protected Awá reserve has been cut down. The Awá’s forests are disappearing faster than any other indigenous area in Brazil.

The future

When he first saw a city, Little Star Awá thought that the inhabitants lived at the top of buildings, like monkeys who sleep in the treetops. He could not understand why some people lived on the streets, and no one was giving them food or shelter.

If their forests fall, the Awá have no hope of surviving as a people. As Blade Awá says, ‘If you destroy the forest, you destroy the Awá too.’

But as long as their forests are standing, all Awá can choose how they want to live, and what they want to take from the world outside.

Survival

Survival International is a global movement for Indigenous peoples’ rights. We are funded almost entirely by concerned members of the public and some foundations, and accept no money from any national government. We have supporters in nearly every country in the world. For 45 years, Survival has helped tribal peoples to defend their lives, protect their lands and determine their own futures.

This campaign was only made possible through the help of

CAFOD • CIMI • Cultures of Resistance • FUNAI • The Staples Trust

Colin Firth • Louis Forline • donations in memory of Laurent Fuchs • Uirá Garcia

Marina Magalhães • Heitor Pereira • Domenico Pugliese • Sam Troughton • Hans Zimmer

and many thousands of Survival supporters across the world. Thank you all.