Living deep in the rainforests of south-east Peru, the Mashco Piro are believed to be the largest uncontacted tribe on Earth, numbering more than 750 people.

In mid-2024, Survival shared photographs and video of a large number of Mashco Piro people emerging onto a riverbank in their territory, which is under massive pressure from logging.

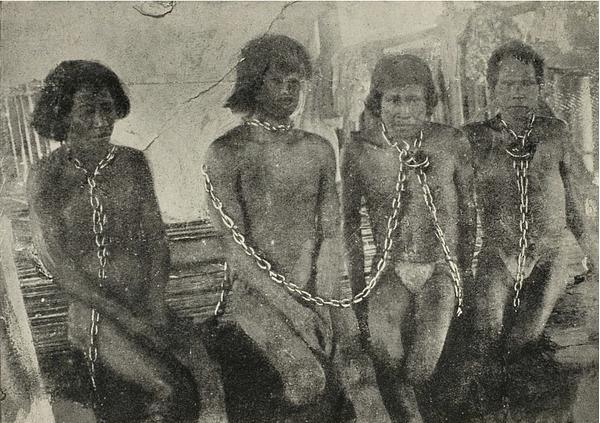

Having survived a traumatic history of massacres and enslavement, they’ve made their determination to defend their territory very clear.

© W Hardenburg

© W Hardenburg

In 2002, the government, responding to lobbying by local Indigenous organization FENAMAD, created the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve to protect the Mashco Piro’s forest. The lush territory, brimming with life, stretches across several river basins near the Brazil border.

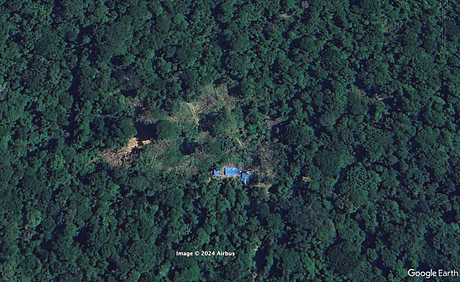

© Ministerio de Cultura de Perú

© Ministerio de Cultura de Perú

But the Reserve covers only a third of the area that FENAMAD had proposed. Large areas of Mashco Piro territory were left unprotected, outside the Reserve. To make matters worse, the government sold off much of this area as logging concessions, giving logging companies the right to fell mahogany and other valuable hardwoods there for decades.

One of the biggest concessions is operated by a logging company called Canales Tahuamanu SAC. Their operations are certified as sustainable and ethical by the Forest Stewardship Council, in a clear violation of its own regulations against logging on Indigenous territory.

In the area where Canales Tahuamanu operates, the loss of wide swathes of their land is pushing the Mashco Piro out of their forest. In recent years they have been appearing on river banks opposite settled communities of a related but contacted people, the Yine. On occasions they take bananas and yucca from the Yine’s vegetable gardens, or ask for machetes and cooking pots.

The Yine language is closely related to that of the Mashco Piro, and they can sometimes communicate when the Mashco Piro emerge to seek food and supplies.

Yine people often hear the Mashco Piro before they see them – they whistle before they emerge from the forest, mimicking the high, thin, trill of a tinamou bird, a warning to stay away while they collect turtles’ eggs from the riverbank, or help themselves to fruit and vegetables.

© Heinz Plenge Pardo / Frankfurt Zoological Society

© Heinz Plenge Pardo / Frankfurt Zoological Society

Even though they have common ancestry, contact between the Yine and Mashco Piro is dangerous for both sides. Uncontacted Mashco Piro have no immunity to common diseases, which could precipitate a deadly epidemic among them. They have also occasionally attacked nearby villagers, for reasons that remain unclear, but are believed to be related to the continuing encroachment into their territory.

Many Yine villagers defend the Mashco Piro. They plant an extra garden – a “chacra” – at the edge of their village where the uncontacted people can help themselves to food, then disappear back into the forest.

The loggers working for Canales Tahuamanu are not only penetrating deep into the forest, they’ve also constructed around 200 kilometers of logging roads. Such roads are historically disastrous in the Amazon, providing an easy way into previously-inaccessible rainforest for colonization and settlement.

Loggers don’t report sightings of the Mashco Piro, for fear of having their operations shut down. A Mashco Piro man told one Yine villager: “The men wearing orange are bad people.” The loggers wear orange jumpsuits.

Canales Tahuamanu has aggressively used the courts to defend its logging activities. In one particularly galling move, they even sued to prevent the Yine entering the rainforest that they share with the Mashco Piro – claiming that since it is protected, the Yine were trespassing.

And after FENAMAD made a statement criticizing them for logging on Indigenous lands during the Covid pandemic, the company took them to court, and won an order that forced FENAMAD to publish a letter endorsing the company’s actions and policies – effectively silencing a strong Indigenous voice in the region.

Noting the aggressive behavior of the company, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples expressed concern for the Mashco Piro’s wellbeing, and about the effects of the lawsuit that the company initiated against FENAMAD. He said: “Attacks and defamations towards environmental human rights defenders and Indigenous leaders seek to delegitimize and create misunderstandings about their work.”

Indigenous organizations in Peru have waged a long campaign for the authorities to extend the Mashco Piro’s reserve. By 2016, all relevant government departments had approved the move, and the official procedure to do so had reached the final stage, a Presidential decree.

But the decree has still not been signed, and the logging continues. And the huge quantities of timber being extracted from the Mashco Piro territory continues to have the FSC stamp of approval, which the company uses to confer legitimacy on its activities.

Survival has been working with local Indigenous organizations FENAMAD and AIDESEP to ensure the Mashco Piro’s land is properly protected. We’re pressuring the Peruvian Government to expand the Madre De Dios Indigenous Reserve to properly protect the Mashco Piro, and to remove all logging companies from their territory. We’re also lobbying the FSC to withdraw their certification of Canales Tahuamanu’s timber.

Following pressure from our campaign, and the support of thousands of people around the world, on July 17 the FSC promised to conduct a review sometime in the future – and referred to a previous “assessment” of the logging company’s permit. That response is weak and unacceptable, which is why Survival International has responded to the FSC.

© Jean-Paul Van Belle

© Jean-Paul Van Belle

"We’ve shared a territory with the uncontacted people for many years, since I was a child. My father used to tell me that when they shout, or shoot an arrow, you shouldn’t go forward, you should go back, because that's how they say ‘Here I am.’

“We’ve always shared territory with them and they’ve never done anything bad to us. They see us around, but they don't bother us. But that was years ago.

“Now, since there have been logging concessions, they feel increasingly pressured and upset because the companies have assaulted them.”

Enrique, Yine man

Act now to support the Mashco Piro

Join the mailing list

There are more than 476 million Indigenous people living in more than 90 countries around the world. To Indigenous peoples, land is life. Find out more about them and the struggles they’re facing: sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.

News from the Mashco Piro

Peru: Uncontacted Mashco Piro dangerously close to resumed logging operations in their territory

In Peru an Indigenous community is reporting that uncontacted Mashco Piro people have recently come into their village.

An avoidable tragedy: Loggers killed by uncontacted Mashco Piro in Peru

An encounter between loggers and uncontacted Mashco Piro people in the Peruvian Amazon has led to tragedy.

Peru: FSC suspends certification of logging company operating in uncontacted Mashco Piro territory

Following demands, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) announced it has suspended logging company Canales Tahuamanu's certification.

Mashco Piro "attack illegal loggers" in Peru

Reports from Peru indicate that there's been a violent clash between the Mashco Piro and illegal loggers

Amazonian Indigenous organizations threaten to boycott FSC over its stance on uncontacted Mashco Piro

Indigenous organizations' statement accuses FSC of delaying decisions to withdraw certification from a logging company operating on uncontacted peoples' land.

Peru: New images show uncontacted tribe dangerously close to logging concessions

Over 50 Mashco Piro people have appeared in Peru in recent days, close to logging concessions.