A massive hydroelectric dam and associated land grabs for plantations threaten the tribes of the Lower Omo River

The tribes have lived in this area for centuries and have developed techniques to survive in a challenging environment.

They have not given their free, prior and informed consent for the dam or the plantations and have already started to lose their livelihoods based on the river’s natural flood cycle.

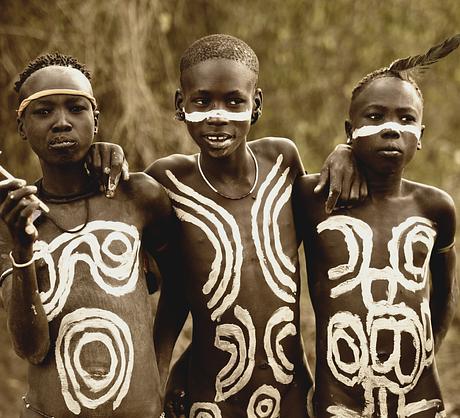

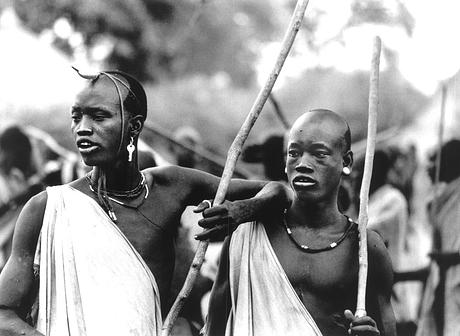

The Lower Omo River in south west Ethiopia is home to eight different tribes whose population is about 200,000.

They have lived there for centuries.

© Ingetje Tadros/ingetjetadros.com

© Ingetje Tadros/ingetjetadros.com

However the future of these tribes lies in the balance. A massive hydro-electric dam, Gibe III, has now been built on the Omo river in order to support vast commercial plantations that are forcing the tribes from their land.

Salini Costruttori, an Italian company, started construction work on the dam at the end of 2006, and it is now complete. The government is now planning to building Gibe IV and Gibe V.

This will destroy a fragile environment and the livelihoods of the tribes, which are closely linked to the river and its annual flood.

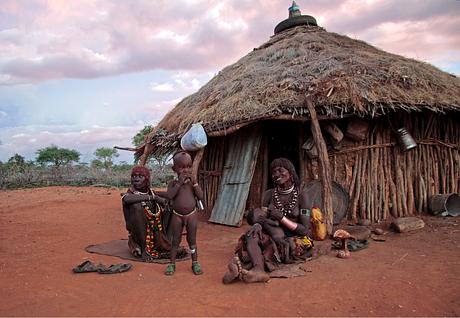

© Eric Lafforgue/Survival

© Eric Lafforgue/Survival

After carrying out preliminary evaluation studies, both the European Investment Bank and the African Development Bank announced in 2010 that they were no longer considering funding Gibe III.

However, China’s largest bank, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, agreed to fund part of the construction of the dam, and the World Bank is funding power transmission lines from the dam.

Hundreds of kilometers of irrigation canals are diverting the life giving waters to the plantations.

Survival and various regional and international organizations, as well as hydrologists and other researchers, believe that the Gibe III Dam and the plantations will have catastrophic consequences for the tribes of the Omo River, who already live close to the margins of life in this dry and challenging area.

![]() Download ‘What Future for Lake Turkana?’ by Sean Avery

Download ‘What Future for Lake Turkana?’ by Sean Avery

Land grabs and forced resettlement

In 2011 the government began to lease out vast blocks of fertile land in the Lower Omo region to Malaysian, Italian, Indian and Korean companies to plant biofuels and cash crops such as oil palm, jatropha, cotton and maize. It has started to evict Bodi, Kwegu, and Mursi people from their land into resettlement areas to make way for the large state-run Kuraz Sugar Project, covering 150,000 hectares but which could eventually cover 245,000 hectares. The Suri who live west of the Omo are also being forcibly resettled to make way for large commercial plantations.

Communities’ grain stores, beehives and their valuable cattle grazing land have been destroyed. Those who oppose the theft of their land have routinely been beaten and thrown in jail. There have been numerous reports of rape and even killings of tribal people by the military, who patrol the region to guard the construction and plantation workers.

The Bodi, Mursi and Suri have been told they have to give up their herds of cattle, a vital part of their livelihood, and may only keep a few cows in the resettlements, where they will become dependent on government aid to survive. Services and food aid in the resettlement camps are often non-existent or of poor quality.

Download Human Rights Watch Report ‘What will happen if hunger comes’.

No adequate environmental or social impact assessments of the impact of the plantations and irrigation scheme have been carried out, nor have the indigenous inhabitants of the valley given their free, prior and informed consent for these projects.

Donors such as the UK and USA, the two largest providers of aid to Ethiopia, have made several visits to the region to investigate human rights abuses, but refuse to make public their findings, such as the reports from the latest donor visit in August 2014.

Although the UK announced in early 2015 that it was no longer funding the Promoting Basic Services programme that many say is connected to forced resettlement, it has increased funding in other areas. There are questions over what mechanism it has in place to ensure that these funds are not facilitating abuse.

Download Oakland Institute’s Report on Ignoring Abuse In Ethiopia.

Ways of life

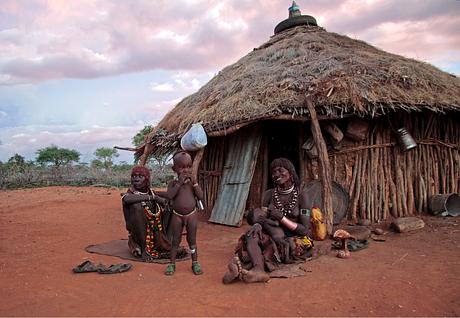

The Lower Omo Valley is a spectacularly beautiful area with diverse ecosystems including grasslands, volcanic outcrops, and one of the few remaining ‘pristine’ riverine forests in semi-arid Africa which supports a wide variety of wildlife.

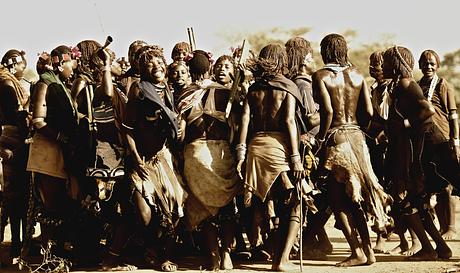

© Ingetje Tadros/ingetjetadros.com

© Ingetje Tadros/ingetjetadros.com

The Bodi (Me’en), Daasanach, Kara (or Karo), Kwegu (or Muguji), Mursi and Nyangatom live along the Omo and depend on it for their livelihood, having developed complex socio-economic and ecological practices intricately adapted to the harsh and often unpredictable conditions of the region’s semi-arid climate.

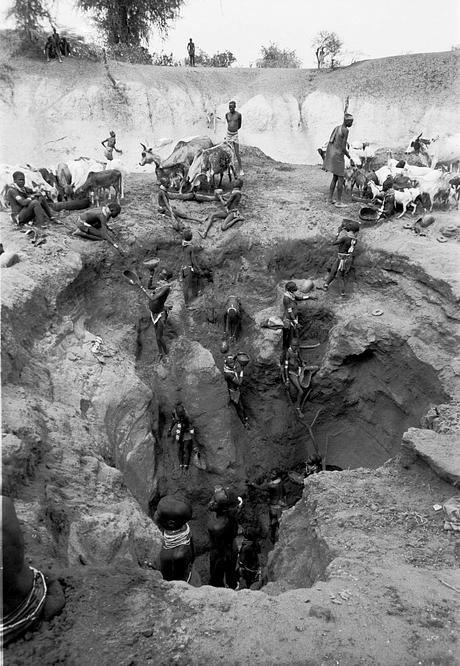

The annual flooding of the Omo River feeds the rich biodiversity of the region and guarantees the food security of the tribes especially as rainfall is low and erratic.

They depend on it to practice ‘flood retreat cultivation’ using the rich silt left along the river banks by the slowly receding waters.

They also practice rainfed, shifting cultivation growing sorghum, maize and beans on the flood plains. Some tribes, particularly the Kwegu, hunt game and fish.

Cattle, goats and sheep are vital to most tribes’ livelihood producing blood, milk, meat and hides. Cattle are highly valued and used in payment for bride wealth.

Tribal song from the Omo Valley. Recording by Daniel Sullivan.

They are an important defence against starvation when rains and crops fail. In certain seasons families travel to temporary camps to provide new grazing for herds, surviving on milk and blood from their cattle. The Bodi sing poems to favourite cattle.

© Magda Rakita/Survival

© Magda Rakita/Survival

Other peoples, such as the Hamar, Chai, or Suri and Turkana, live further from the river but a network of inter-ethnic alliances means that they too can access the flood plains, especially in times of scarcity.

Despite this co-operation there are periodic conflicts as people compete for natural resources. As the government has taken over more and more tribal land, competition for scarce resources has intensified. The introduction of firearms has made inter-ethnic fighting more dangerous.

No voice

For years the tribes of the Lower Omo Valley have suffered from the progressive loss of access to and control of their lands. Two national parks were set up in the 1960s and 1970s where they have been excluded from managing the resources.

© Magda Rakita/Survival

© Magda Rakita/Survival

In the 1980s, part of their territory was turned into a state-run irrigated farm and recently the government has begun leasing out huge tracts of tribal land to foreign companies and governments so that they grow cash crops including biofuels.

The tribal peoples who have been using the land for generations to grow their own subsistence crops and to graze their livestock, have had no say in the matter.

Although the Ethiopian Constitution guarantees tribal peoples the right to ‘full consultation’ and to ‘the expression of views in the planning and implementations of environmental policies and projects that affect them directly’, in practice consultation is rarely carried out fully and appropriately.

The Lower Omo Valley peoples make all public decisions after extensive community meetings among all adults. Very few speak Amharic, the national language, and literacy levels are the lowest in the country which means they have little access to information about developments which affect them.

A USAID official who visited the Lower Omo in January 2009 to assess the impacts of the Gibe III dam reported that the indigenous communities knew either nothing or virtually nothing about the project.

With the aim of limiting debate on controversial policies and restricting awareness of human rights, the government published a decree in February 2009 stating that any charity or NGO which receives more than 10% of its funding from foreign sources (which is virtually every charity in Ethiopia) cannot promote human and democratic rights.

In July 2009, the Southern Region’s Justice Bureau revoked the licences of 41 local ‘Community Associations’, accusing them of not co-operating with government policy. Many observers believe the revocation is really an attempt by the government to stamp out discussion of and opposition to Gibe III.

Gibe III dam

In July 2006 the Ethiopian government signed a contract with the Italian company Salini Costruttori to build Gibe III, the biggest hydro-electric dam in the country. In violation of Ethiopia’s laws, there was no competitive bidding for the contract.

© Survival International

© Survival International

Work started in 2006 with a budget of 1.4 billion euros. The dam is now complete and the government started filling the reservoir upstream in 2015. This has put an end to the natural floods. No artificial flood was released in 2015, and the flood released in 2016 was too low to sustain the tribespeople’s crops.

The dam blocks the south western part of the Omo River which runs for 760 kms from the highlands of Ethiopia to Lake Turkana in Kenya. The Lower Omo Valley is a UNESCO World Heritage site, in recognition of its archaeological and geological importance. Here the Omo flows through the Mago and Omo National Parks, home to several tribes.

Experts say that the restricted flow of the river will cause Lake Turkana to dry up by as much as two-thirds. This will destroy the fisheries on which hundreds of thousands of indigenous people depend.

Ethiopian environmental law stipulates that an environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) must be carried out before any project is approved. Despite this, the Ethiopian Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) approved the ESIA retrospectively, in July 2008, two years after construction work started.

The ESIA was carried out by an Italian company, CESI, and paid for by EEPCo (Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation) and Salini, raising questions over its independence and credibility. Its report, published in January 2009, found in favor of the project, stating that the impact on the environment and tribes concerned will be ‘negligible’ and even ‘positive’.

© Serge Tornay/Survival

© Serge Tornay/Survival

According to independent experts, the dam, plantations and irrigation canals will have an enormous impact on the delicate ecosystem of the region by altering the seasonal flooding of the Omo and dramatically reducing its downstream volume. This will result in the drying out of much of the riverine zone and will eliminate the riparian forest. Indigenous people such as the Kwegu who rely almost exclusively on fishing and hunting will be destitute.

As the natural flood with its rich silt deposits disappears, subsistence economies are threatened with collapse, with at least 100,000 tribal people facing food shortages. The potential for inter-ethnic conflict will increase as people compete for scarce and dwindling resources.

For more information, see this in-depth report by Dr Claudia J. Carr of the Africa Resources Working Group.

Survival has lodged complaints about this abuse with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Both complaints are ongoing.

Act now to support the Omo Valley tribes

Join the mailing list

There are more than 476 million Indigenous people living in more than 90 countries around the world. To Indigenous peoples, land is life. Find out more about them and the struggles they’re facing: sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.

News from the Omo Valley tribes

Kenya: UN says Lake Turkana is endangered

UN body says Lake Turkana, home to tribes in Kenya and Ethiopia, is in danger due to dam building upstream

Catastrophic dam inaugurated today in Ethiopia

A megadam is being inaugurated today that puts hundreds of thousands of people at risk

Survival reports Italian corporation to OECD over dam disaster

Survival files OECD complaint against Italian engineering firm for devastating consequences of dam in Ethiopia

Experts meet to 'prevent humanitarian catastrophe' in Ethiopia and Kenya

Representatives of tribal peoples from Kenya and Ethiopia and international experts are meeting to expose the threats to 500,000 people.

Exposed: Forced evictions in Ethiopia – what the UK government tried to cover up

Survival has acquired two revealing reports of donor missions in August 2014.

Reports surface of 'massacre' of Hamar tribespeople in Ethiopia

Escalating violence in Ethiopia's Lower Omo Valley has reportedly left dozens dead and many more at risk.