'Human safaris' threaten the Ang

Although India’s Supreme Court in 2002 ordered that the highway through the Ang’s reserve should be closed, it remains open – and tourists use it for ‘human safaris’ to the Ang.

Poachers enter the Ang’s forest and steal the animals they rely on for their survival. They have also introduced alcohol and drugs and are known to sexually abuse Ang women.

The Ang have only been in (limited) contact with the settlers who live around their territory since the 1990s and remain vulnerable to diseases. In 1999 and 2006, the Ang suffered outbreaks of measles – a disease that has wiped out many Indigenous peoples worldwide following contact with outsiders.

The Ang used to be known as “Jarawa” which means “stranger” in a neighbouring Great Andamanese language, but they call themselves “Ang” which means “We people.”

© Salomé

© Salomé

The surviving Indigenous peoples of the Andaman Islands – the Ang, Great Andamanese, Onge and Sentinelese – are believed to have lived in their Indian Ocean home for thousands of years.

They, and the Indigenous Shompen and Nicobarese of the Nicobar Islands are now vastly outnumbered by the approximately 400,000 Indian settlers, who have moved to the islands.

The Ang

Today, approximately 450 of the nomadic Ang people live in groups of 40-50 people in chaddhas – as they call their homes.

Like most Indigenous peoples who live self-sufficiently on their ancestral lands, the Ang continue to thrive, and their numbers are steadily growing.

They hunt pig and turtle and fish with bows and arrows in the coral-fringed reefs for crabs and fish, like the striped catfish-eel and the toothed pony fish. They also gather fruits, wild roots, tubers and honey.

Both Ang men and women collect wild honey from tall trees. During the honey collection the members of the group sing songs to express their delight. The honey-collector chews the sap of leaves of a bee-repellant plant, such as Ooyekwalin, which they will then spray with their mouths at the bees to keep them away. Once the bees have gone the Ang can cut the bee’s nest, which they put in a wooden bucket on their back.

© Survival

© Survival

A study of their nutrition and health found their ‘nutritional status’ was ‘optimal’. They have detailed knowledge of more than 150 plant and 350 animal species.

For hundreds of years, the Ang vehemently resisted all contact with outsiders and defended their territory from invasion, like their neighbors the Sentinelese. However, eventually in 1998, they began to emerge from their forest without their bows and arrows and to occasionally visit nearby settlements. While the Ang are no longer uncontacted, they are still a very isolated people, and are regarded as being “in initial contact”, meaning they are still very vulnerable to exploitation from outsiders.

In 1990 the local authorities revealed their long-term ‘master plan’ to settle the Ang in two villages with an economy based on fishery, suggesting that hunting and gathering could be their ‘sports’. The plan was so prescriptive it even detailed what style of clothes the Ang should wear. Forced settlement had been fatal for other peoples on the Andaman Islands, just as it has been for most recently contacted Indigenous peoples worldwide.

Following a vigorous campaign by Survival and Indian organisations, including providing expert witness testimonies to the High Court, the resettlement plan was abandoned. Simeon Tshakapesh, Chief of the Mushuau Innu in eastern Canada described in his testimony how being ‘settled’ can be ‘a death sentence for a self-sufficient and unique people” adding “I implore you to learn from our situation before making any decisions which will drastically impact the lives of the Jarawa [Ang] people.”

In 2004 the authorities announced a radical new policy: the Ang would be free to choose their own future, and that outside intervention in their lives would be kept to a minimum.

What problems do the Ang face?

Despite the positive policy, the Ang continue to face many threats:

-

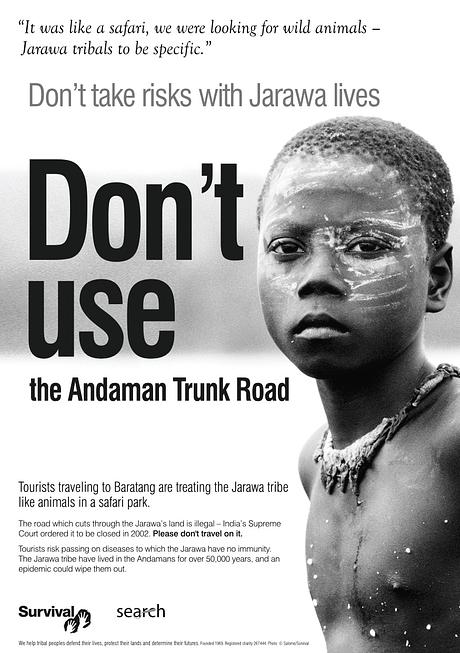

The road that cuts through their territory brings thousands of outsiders, including tourists, into their land. The tourists treat the Ang like animas in a safari park.

- Illegal hunting, fishing and gathering, from both local and foreign poachers, remains a serious threat to the Ang’s survival. The theft of the food they rely on risks robbing them of their self sufficiency. Without the food they hunt, fish and gather they will not survive.

-

They also remain vulnerable to outside diseases to which they have little to no immunity. In 1999 and 2006, the Ang suffered outbreaks of measles – a disease that has wiped out many peoples worldwide following contact with outsiders. An epidemic could devastate the Ang.

-

Ang women have been sexually abused by poachers, settlers, bus drivers and others.

Attempts to ‘mainstream’ the Ang

In India, ‘mainstreaming’ refers to the policy of pushing an Indigenous people to join the country’s dominant society. It has a devastating effect on Indigenous peoples. It strips them of their self-sufficiency and sense of identity, and leaves them struggling at the very margins of society. Rates of disease, depression, addiction and suicide within the Indigenous community almost inevitably soar.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands’ member of parliament has called for ‘quick and drastic steps be taken to bring the Jarawa [Ang] up to the basic mainstream characteristics’ and for children to be sent to residential schools in order to ‘wean’ the children away from their own people. He described the Ang as being ‘in a primitive stage of development’ and ‘stuck in time somewhere between the stone and iron age’. In 2024 he requested money from the government because the Islands are “home to most primitive tribal of the world [sic]” who need programs for their “development”.

These requests, however, has not come from the Ang, who show no sign of wanting to leave their life in the forest. The fate of the Great Andamanese people serves as a vivid warning of what may happen to the Ang unless their rights to control who comes onto their land and to make their own decisions about their ways of life are recognized.

"Human safaris"

A serious threat to the Ang’s existence comes from a highway through their forest known as the Andaman Trunk Road which brings outsiders into the heart of their territory.

The road has encouraged ‘human safaris’, where tour operators drive tourists along the road in the hope of ‘spotting’ Ang people, something reminiscent of the horrific ‘human zoos’ from the colonial era.

Since 1993 Survival has been lobbying the Indian government to close the Andaman Trunk Road, believing that only the Ang should decide if, when and where outsiders traverse their land.

© Search/Survival

© Search/Survival

In 2002, the Indian Supreme Court ordered the closure of the road, yet it still remains open.

In 2013, following a campaign by Survival and local organization Search, India’s Supreme Court banned tourists from the road for seven weeks, reducing the traffic along the Andaman Trunk Road by two thirds. But the ban was lifted after the Islands’ authorities changed their own regulations in order to let the ‘human safaris’ continue.

In October 2017, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands' Authorities opened the long-called for alternative sea route to Baratang. This sea route was supposed to stop the human safaris. But despite the authorities’ promise that all tourists would have to use the sea route, this has not happened, and the illegal market in human safaris along the road is still flourishing.

Survival has been calling for the Andaman and Nicobar Islands' authorities to stop the human safaris, clamp down on poaching and ensure that those arrested are prosecuted.

Join the mailing list

There are more than 476 million Indigenous people living in more than 90 countries around the world. To Indigenous peoples, land is life. Find out more about them and the struggles they’re facing: sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.

News from the Ang

Andaman tribal women widowed by poisoning remarry

Four women from the tiny Andaman tribe the Onge, who were widowed last month in a tragic poisoning incident, have remarried.

Outrage as tour operators sell “human safaris” to Andaman Islands

Andaman government fails to stop degrading and exploitative tribal tourism despite opening of 'alternative sea route'

End in sight for India's notorious human safaris

Exploitative tribal tourism damaging lives of recently contacted tribe could end, after Survival-led boycott

India misses deadline to end Andaman 'human safaris'

Authorities on India's Andaman Islands have failed to end 'human safaris' to the vulnerable Jarawa.

Major investment in 'human safaris' road sparks fears for tribe

Plans for widening and building bridges along the Andaman Trunk Road have been condemned by Survival

Survival condemns regressive election pledges on Jarawa tribe

Regressive pledges include bringing the Jarawa tribe into the mainstream; and removing a protective buffer zone around their reserve.