We are inside it, and it is inside us

Tribal societies depend on their environments. To mark the UN conference on sustainable development, Survival portrays some of the beliefs and practices of the world’s tribal peoples.

From the agriculturalists of the Amazon to the hunter-gatherers of Africa; from the cultivators of Bangladesh to the hunting peoples of Canada, tribal peoples have found ingenious ways of catering for their needs over thousands of years without destroying their environments.

Many believe that for nature to endure, a long-term attitude to the caretaking of the earth is fundamental. Respect for the limits of nature is essential: to destroy the earth, or to take more than is needed is not only self-defeating, but a neglect of future generations.

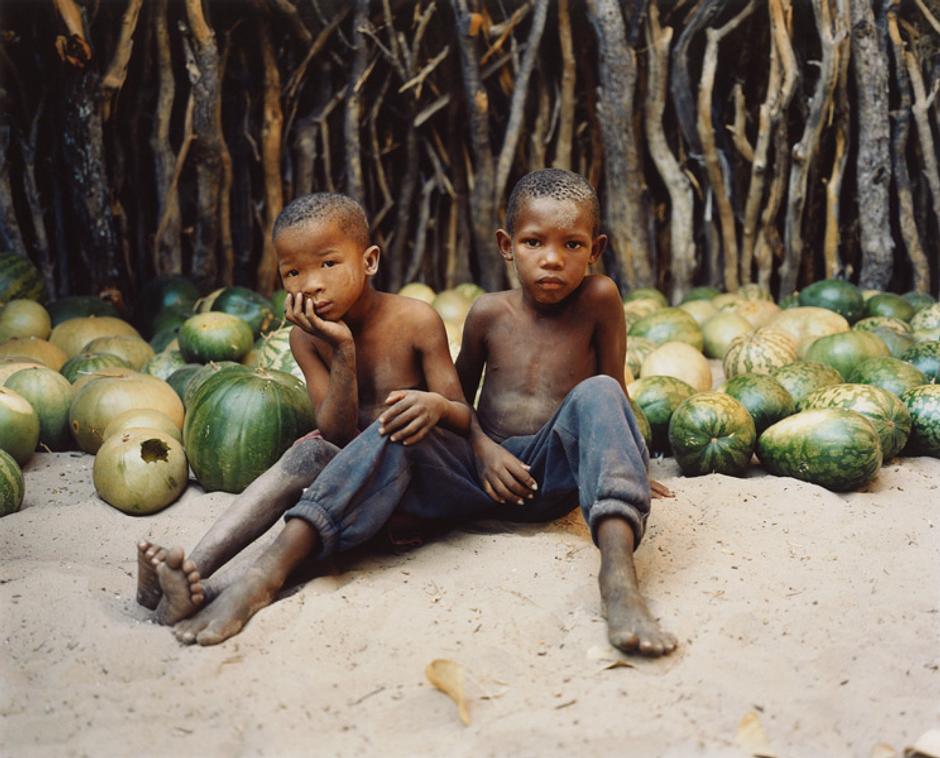

We are not here for ourselves, said Gana Bushman Roy Sesana. We are here for our children, and the children of our grandchildren.

© Lottie Davies/Survival

Many parts of the world that are the richest in biodiversity remain so due to the care of the indigenous peoples who live in them; the Jarawa people inhabit the remaining tracts of virgin rainforest in the Indian Ocean’s Andaman Islands.

It is self-evident, says Stephen Corry of Survival International. Where tribal peoples have been allowed to continue living on their lands, biodiversity can be much higher than in other kinds of protected areas.

© Survival

The Moken people of the Mergui Archipelago in the Andaman Sea eat fish, dugong, sea cucumber and crustaceans, which they catch with harpoons, spears and hand-lines.

Hook Suriyan Natale, a Moken man from the Surin Islands, says, such sustainable fishing methods ensure that there will always be fish left in the sea.

The Surin Islands have remained largely unaffected by the presence of the Moken: they take from their environment only what they need to survive. The nomadic nature of the traditional way of life also means that forest and marine resources are rotated, and no one resource or area is over-harvested.

© Cat Vinton/Survival

Tribal peoples typically have a holistic view of nature and see humanity as part of, not separate from, the Earth.

We have lived in the Mau Forest for hundreds of years, say the Ogiek of Kenya. The forest is an ecological haven and we are conservationists, so we treat it well and live in balance with it.

We harvest honey twice a year based on the pollination habits of the bees and on the trees that flowered during the long and short rains.

© Yoshi Shimizu

We love the forest as we love our own bodies, say the ‘Pygmy’ peoples who live in the densely forested regions of Central and West Africa.

Pygmy men scale immense trees in search of honey, and are such proficient mimics they can imitate the sound of a distressed antelope in order to lure another out of the bush.

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

We know our forest land well, says Davi Kopenawa Yanomami. The environment is not separate from ouselves; we are inside it, and it is inside us; we make it and it makes us.

Such immersion in nature over thousands of years has resulted in an encyclopaedic knowledge of native animals, plants and herbs.

The Yanomami use around 500 species of plants on a daily basis for food, building materials and hunting poisons. Babies’ slings are made from silk-grass twine, arrow shafts from the stems of pampas grass and salt is extracted from the ashes of the Taurari tree.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

Penan hunters have long lived in harmony with the ancient rainforest of Sarawak in Borneo, one of the most biologically rich forests on earth.

Until the 1960s all Penan people lived as nomads, moving camp frequently in search of boar, and following the cycles of fruiting trees and wild sago palm.

Their homes – sulaps – were constructed from large wooden poles, lashed together with rattan strips and tiled with giant palm leaves.

© Andy Rain & Nick Rain/Survival

Tribal people of the Baliem valley of New Guinea probably developed agriculture long before the ancestors of the Europeans.

© Grenville Charles/Survival

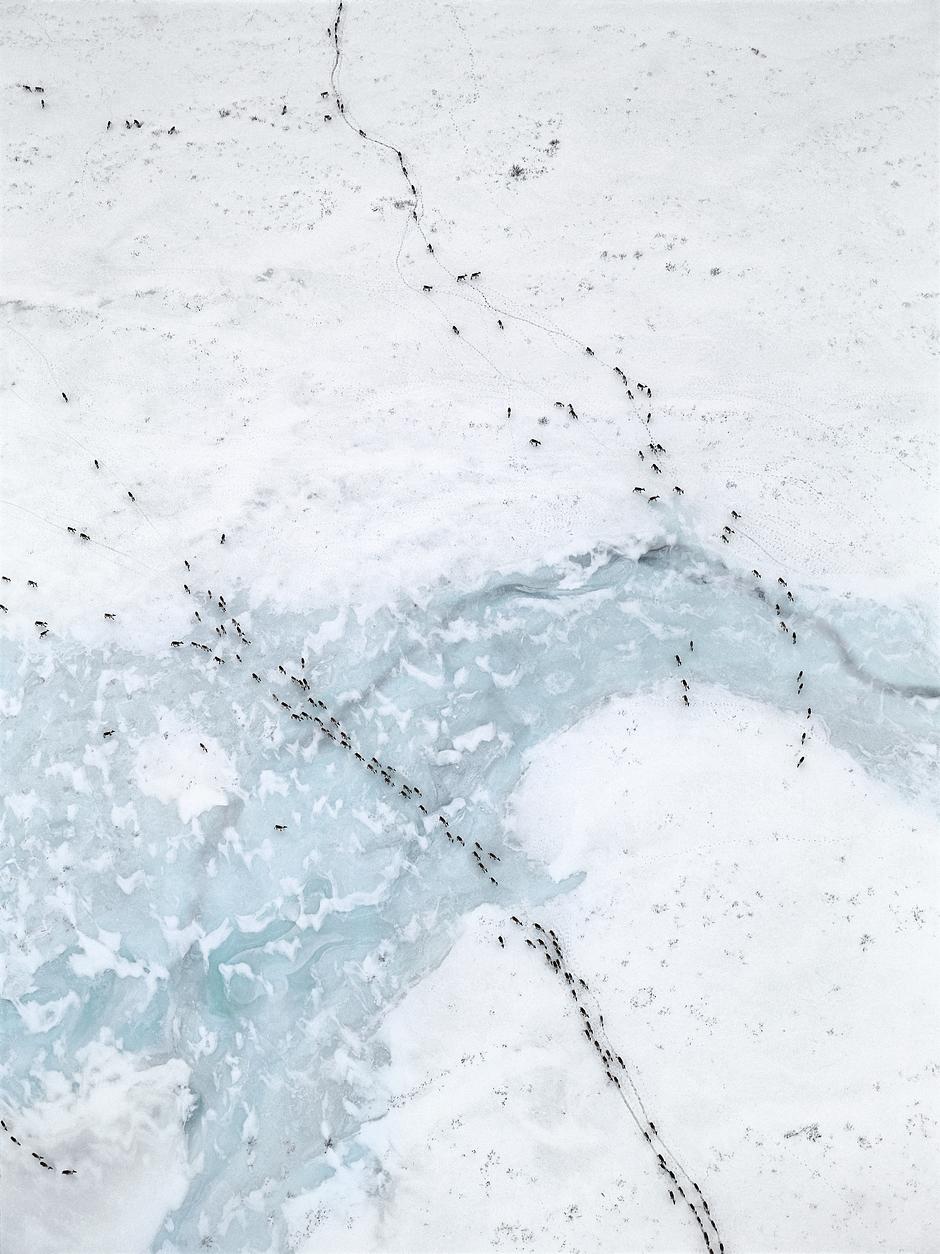

The existence of the Innu in north-eastern Canada has rested on their understanding of the seasonal migrations of caribou across ‘nutshimit’, their tundra home.

The Innu revere the caribou; they scrupulously share the meat and carefully preserve the leg bones; to throw them away is to disrespect kanipinikat sikueu, the ‘Master’ spirit of the caribou.

No part of the caribou is wasted; antlers are hung high in the trees.

© Subhankar Banerjee/Survival

With traditionally low-carbon and sustainable lifestyles, tribal people are well-placed to give advice on the solutions needed to mitigate climate change.

It is ironic that as ecoystems are destroyed, so the cultures with an understanding of them are also threatened.

Tribal peoples are the natural guardians of their eco-systems, says Stephen Corry of Survival International. So it seems logical to protect the world’s fragile places by securing the land rights of the indigenous communities who have in-depth knowledge of their territories.

© Claudia Andujar/Survival

Only we, the indigenous people, know how to protect the rainforest, says Davi Kopenawa Yanomami.

Give us back our lands before the forest dies.

© Hutukara/ISA

Think not forever of yourselves, O Chiefs,

Nor of your own generation

Think of continuing generations of our families,

think of our grandchildren

And those yet unborn,

Whose faces are coming from

beneath the ground.

Peacemaker, Iroquois Confederacy, USA

© Clive Dennis/Survival

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...