We didn't know about sugar in the blood

On World Diabetes Day, Survival examines the causes behind the escalating rates of type 2 diabetes among the Innu of north-eastern Canada.

Photographs by Dominick Tyler.

An Innu man and woman push a toboggan laden with belongings along a frozen waterway in north-eastern Canada.

The photograph shows life as it used to be for the indigenous Innu tribe who, 50 years ago, were still living as semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers.

During the sub-arctic winters, they snow-shoed across the vast interior in search of migrating caribou. In the summer months, when the ice melted, they traveled by handmade birch-bark canoes to the Atlantic coast. They were largely strong, healthy and independent.

Today, they are a sedentary people beset by chronic mental and physical health problems, including an epidemic of diabetes – a western disease that only developed after they were pressured into settling in fixed communities.

© Georg Henriksen

Nitassinan, as the Innu call their homeland of spruce forests and snaking rivers, had been theirs for approximately 7,500 years; it had crafted their history, skills, cosmology and language, and had provided a diverse and nutritious diet.

As well as caribou, the Innu also hunted bear, marten and fox, and small game such as beaver, porcupine, partridges, ptarmigan, ducks and geese.

They fished for trout, salmon and arctic char in the deep lakes, and gathered blueberries and crab apples in the fall.

© Dominick Tyler

During the 1950s and 1960s, however, the Canadian government and Catholic Church pressurized the Innu into settling in fixed communities.

Much of their land was confiscated; hunting for caribou was strictly regulated.

The authorities enforced many processes that attempted to alter the Innu and diminish the many sources of their uniqueness as a people, says Professor Colin Samson, who has worked with the Innu for decades.

© Dominick Tyler

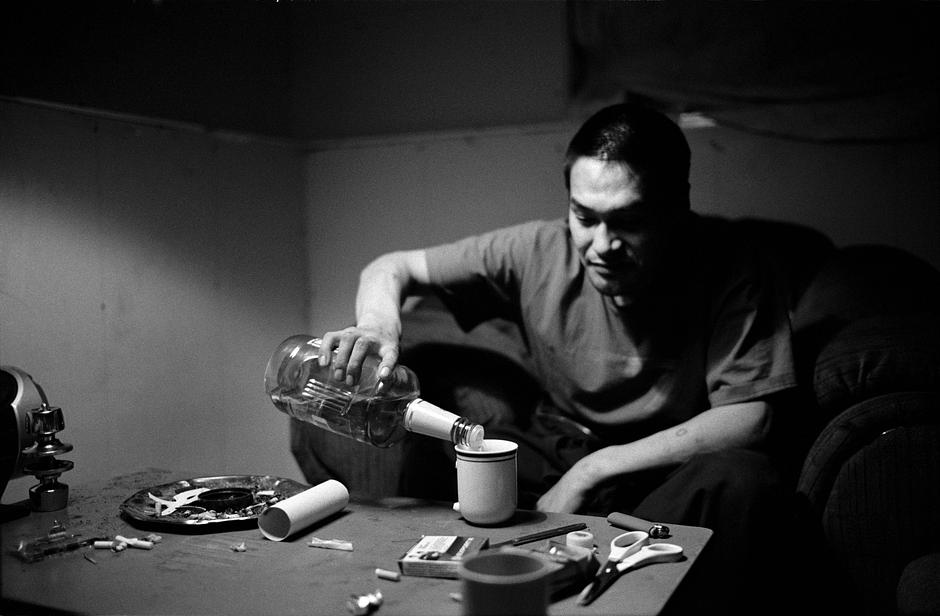

Instead of leading purposeful, healthy, self-sustaining lives in harmony with the natural world, the Innu were suddenly deprived of movement and meaning, and forced to adopt a western-style diet vastly different to their own.

The mental and physical health consequences were disastrous.

Rates of alcoholism and suicide soared, just as their self-esteem plummeted and their collective identity started to erode.

And as the traditional Innu diet was replaced by a diet high in saturated fats, refined sugars and salt, so obesity became commonplace in Innu communities, as did its pathological corollary: diabetes.

© Dominick Tyler

When I was a kid, 15 years ago, there was zero diabetes and cancer. Our grandparents were hunting and eating healthy country foods, says Michel Andrew, an Innu man from Sheshatshiu.

It hurts me to think about it. Now this terrible disease is spreading too fast in our communities. People are drinking too much, and buying food from the store, and not exercising.

© Dominick Tyler

Once the initial impacts of contact have passed through an indigenous population, chronic health problems frequently follow as an entire way of life is destabilised, says Stephen Corry, Director of Survival International. Typically, life expectancies decrease when hunter-gatherers are settled, not increase.

Survival has campaigned for Innu rights for many years, calling on the Canadian government to rethink its approach to negotiations with the Innu.

Colin Samson says, Diabetes rates are directly related to abrupt changes in diet; from a wild food diet to a junk food diet.

Health problems associated with dietary change were not as acute or did not occur if indigenous people were able to maintain a diversified diet of plant, animal and fish foods.

© Adam Hinton/Survival

Before the 1950s, chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease had been relatively rare among the Innu.

Studies suggest that this may in part be due to the high content of Omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants in their traditional diet.

Colonial explorers visiting isolated peoples regularly reported how strong and healthy the people were, recording ‘fine teeth’, ‘excellent skin’ and ‘muscular physiques’, says Stephen Corry.

© Katie Rich

Today, 15% of the Innu community in Sheshatshiu has been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, as has 9% of the population of Natuashish.

We do not know whether the elevated levels are because there is now more testing, or more diabetes, says the Diabetes Nurse Educator at the Mani Ashini Health Centre in Sheshatshiu. However, many people in both communities have not even been tested for the disease, so we suspect that the actual rate may be as high as 30%.

in 2008, there were no kidney dialysis machines in Happy Valley-Goose Bay hospital, the nearest to Sheshatshiu. Today, there are five.

© Dominick Tyler

Diabetes is a global problem – affecting 8.3 % of the adult population, according to the International Diabetes Federation – while the UN states that 50% of indigenous adults over the age of 35 worldwide have type 2 diabetes.

In March 2012, a group of experts gathered for a conference on diabetes in indigenous populations, when it was revealed that in Canada, indigenous people represent 2.5% of the Canadian population yet a staggering 45% of the youth with new onset type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes has reached epidemic proportions in indigenous communities and places the very existence of these communities at risk, says Professor Jean Claude Mbanya, President of the International Diabetes Federation.

Yet most indigenous peoples with diabetes around the world are never diagnosed; they never receive treatment for diabetes and die from the condition without knowing the reason for their suffering.

© Dominick Tyler

In the winter of 2009, Michel Andrew, also known as ‘Giant’, had a dream in which his grandfather spoke to him.

Get up and help your people, he told his grandson. Get up and walk.

Giant gave up drinking, took up his toboggan and walked north across the frozen waters of Lake Melville.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

Giant’s aim was to raise awareness of his people’s diabetes problem, reconnect young Innu to nutshimit (the country), and demonstrate that natural foods are far healthier than processed and store-bought items and sugared drinks.

Imagine, in ten years’ time, the whole community could have diabetes, says Giant. Everyone could be losing limbs. I want to help my people by setting up cooking programmes to help educate communities about nutrition, and reduce levels of diabetes.

Over the course of three years, Giant walked almost 4,000 kms.

© Alex Andrew

Innu teenagers were taught traditional skills by the Elders during Giant’s walk.

Joel – at 15 the youngest member – regularly sniffs gas with his friends when at home in the community of Natuashish.

In the country, however, he feels strong. The country feels good. I like being sober, he says.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

During the walk the Innu hunted for and ate fresh caribou meat.

Caribou has over twice the protein content of tinned meat, one tenth the amount of saturated fat, three times the amount of vitamin C and nearly nine times the amount of iron.

What the kids eat today is making them sick, says Innu Elder, Joe Pinette. What they ate in the country never made them sick. Once their parents bought junk food, the kids started to have problems.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

Ptarmigan feathers lie on snow stained red with caribou blood, and studded with husky prints.

Ptarmigan has ten times as much niacin than other meats and fish.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

For centuries, the health of many tribal peoples has been destroyed by invaders forcibly removing them from their lands and imposing their own ways of life. Yet when living according to their traditions, on their own lands, tribal peoples are typically healthy, happy, strong and vibrant.

Many tribal peoples have made different choices from most in industrialized societies, preferring to be mobile rather than settled, opting for hunting or herding rather than agriculture, says Stephen Corry.

But this does not, of course, mean they are more backward than anyone else, or need to adopt a western way of life.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

You might as well expect the rivers to run backward as that any man who was born free should be content to be penned up and denied liberty to go where he pleases.

If you tie a horse to a stake, do you expect he will grow fat?

If you pen an Indian up on a small spot of earth and compel him to stay there, he will not be content; nor will he prosper.

Chief Joseph, 1879

© Alex Andrew

Three Innu walkers approach the high barren country near Border Beacon, Labrador, March 2012.

Changing the balance of life back to country-based activities would address both the primary causes of the crisis and improve the health and well-being of the Innu, says Jules Pretty, Professor of Environment and Society at the University of Essex.

Improving indigenous peoples’ health cannot be achieved through medications alone, says Stephen Corry. Action is urgently needed to enable the Innu and other indigenous peoples to reconnect with their lands and gain control over their futures.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...