Universal Children's Day

To mark Universal Children’s Day on November 20, Survival International publishes a gallery of photographs of tribal children, insights into their fascinating ways of life and the threats that jeopardize their futures. (WARNING: contains disturbing image on slide no. 5).

The world’s tribal children are the inheritors of their peoples’ ways of life, languages and ecosystems, from the Amazonian rainforest to the Siberian tundra.

For centuries, however, these lands have been logged, mined, cleared and torched, and the peoples indigenous to them have rarely been consulted and frequently evicted.

The loss of their lands is often at the root of tribal children’s suffering. Infant mortality, juvenile addictions and suicide – as well as chronic diseases and reduced life expectancy – are just some of the consequences of trying to forcibly assimilate tribal peoples and their children into mainstream cultures.

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

In the lush forests of the Brazilian Amazon, Awá children are taught from a young age how to survive.

Boys play with miniature bows and arrows to learn the skills of a successful hunter; girls are taught how to collect fruit and make açaí juice.

All children develop an encyclopaedic knowledge of the surrounding forests.

© Domenico Pugliese

This unique knowledge, however, is severely endangered.

Despite a government operation in early 2014 to remove all illegal invaders from Awá land, some have returned. 30% of one legally-protected Awá reserve has already been cut down by loggers and ranchers.

The outsiders are coming, and it’s like our forest is being eaten up, Takia, an Awá man, said.

Uncontacted Awá and their children are particularly vulnerable to forces from outside: a common cold could kill an entire community, as uncontacted peoples have little resistance to imported diseases.

Survival is now calling on the Brazilian authorities to put in place a permanent land protection program to keep the invaders out of the Awá territory.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

The Guarani in Brazil are thought to have been one of the first peoples to be contacted after Europeans arrived in South America.

They once occupied a homeland of forest and plains in Brazil totaling some 217,000 square miles; today, having lost most of their land, they are squeezed onto tiny patches of land surrounded by cattle ranches and vast fields of soya and sugar cane. Some have no land at all, and live camped by roadsides.

Over the past 30 years more than 625 Guarani Indians have killed themselves. The majority of the victims are between 15 and 29 years old, but the youngest recorded victim was just 9.

© Paul Patrick Borhaug/Survival

(WARNING: contains disturbing image).

The Guarani are committing suicide because we have no land, said a Guarani man.

In the old days, we were free. Now we are no longer. So our young people think there is nothing left.

They sit down and think, they lose themselves and then they commit suicide.

© João Ripper/Survival

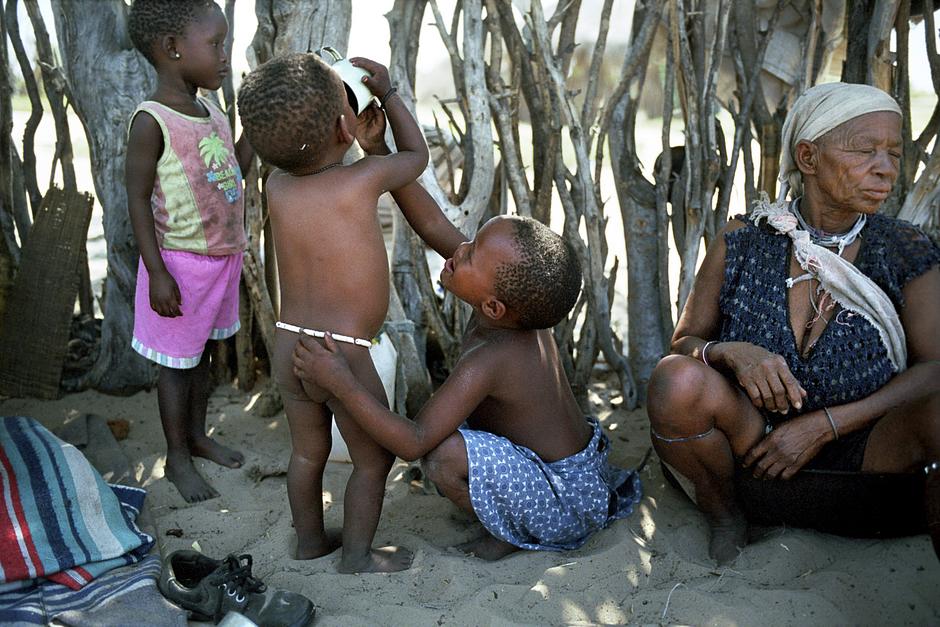

I grew up a hunter, said Roy Sesana. I cannot read. But I do know how to read the land and animals. All our children could.

The Bushman peoples are the original inhabitants of Southern Africa. Over thousands of years, they developed hunting practices that have allowed them to provide for the community’s needs without destroying the local environment.

Young boys were given toy bows and arrows to hunt rats and small birds, and taught how to kill spring hare or make blankets from gemsbok skin. Girls as young as five helped their mothers gather plants, berries and tubers. Children learned to be both brave and humble, and were taught that generosity was to be admired and selfishness disliked.

Today, however, after the forced evictions from their hunting grounds in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), many Bushman children live in squalid eviction camps, known to them as “places of death”, where AIDS is rife, and a life devoid of hunting and long-established rituals foments depression and alcoholism.

© Survival International

Bushmen children are only allowed free entry to the reserve up to the age of 16, after which they too are only allowed in on month-long permits.

Survival International has launched a boycott of tourism to Botswana over Botswana’s continuing attempts to force the Bushmen off their ancestral land in the CKGR, while promoting the reserve as a tourist destination and using images of Bushmen and their children in their marketing materials.

Unless all Bushmen are allowed to return unimpeded to their ancestral lands, their children will not inherit the unique ways of life of their great-grandparents, but a life of dependency, despair and ill-health, says Stephen Corry, Director of Survival.

© Dominick Tyler

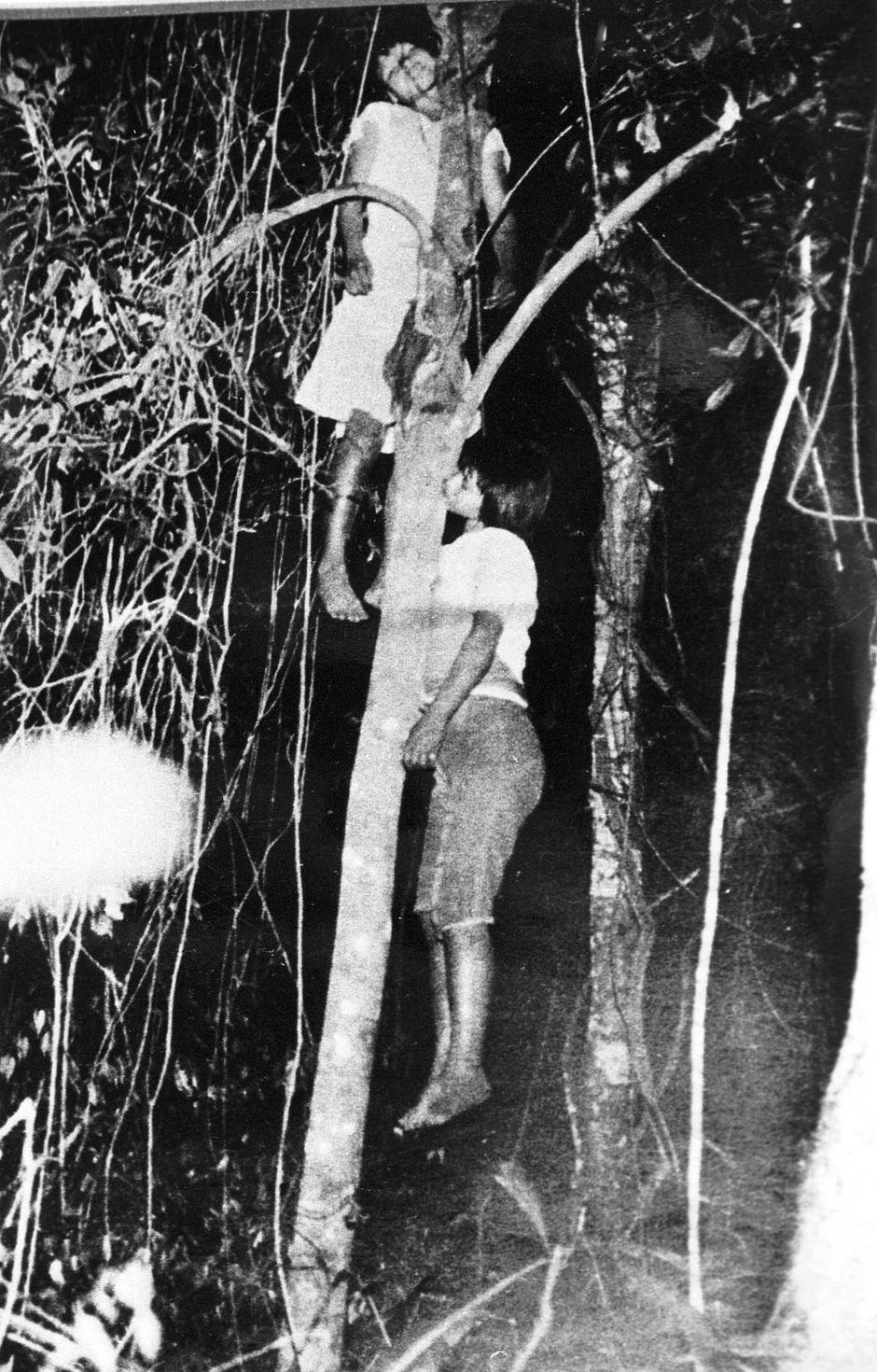

Young Yanomami boys of the Brazilian Amazon learn to ‘read’ the spoor of animals, use plant sap as poisons and shin up trees by tying their feet together with liana vines.

In those days, my Mother always took me with her into the forest to look for crabs, fish with timbó, or gather wild fruits, says Davi Kopenawa, spokesman for the Yanomami people.

I would also go with her to the fields when we needed to harvest cassava, bananas, or to cut firewood. Sometimes the hunters would also call me at daybreak when they left for the forest. That was how I grew up in the forest.

© Claudia Andujar/Survival

In recent years there have been disturbing reports that Yanomami teenagers and young women have been victims of sexual abuse by soldiers of the Brazilian Army. Having been lured by gifts of food and alcohol, sexual abuse has resulted in unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhea and syphilis.

When the Army arrived, they started to tease the Indians, says Davi Kopenawa. They asked the women to sleep with them and gave them food of rice and flour. They used our Indians. Now they are sick. The soldiers have transmitted diseases; the women are sick with gonorrhea and syphilis.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

In the Congo Basin, a Baka “Pygmy” mother carries her baby while she gathers wild plants and nuts in the forest.

The Baka in southeast Cameroon are being illegally forced from their ancestral homelands in the name of “conservation” because much of their land has been turned into “protected areas” – including safari-hunting zones. Now they face arrest and beatings, torture and death at the hands of anti-poaching squads supported by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

The health of many Baka, Mbendjele and other “Pygmy” children in many regions has suffered in various ways following sedentarization, due to poor nutrition, for example, and higher incidence of communicable diseases.

Hunting for game in the rainforests across Central Africa is becoming harder due to over-hunting – in response to the demand for bushmeat in logging camps and cities across the region – and the confiscation of legally hunted bushmeat by the authorities in many of the area’s national parks.

Some Mbendjele children in the Republic of Congo are also being employed by immigrant market traders to clean out latrines; often they are only paid in glue to sniff.

© Survival International

North-east Canada is a sub-arctic expanse of tundra, lakes and forests. Until the second half of the 20th century, the Innu people lived here as nomadic hunters, relying largely on the herds of caribou which migrate through their land every spring and autumn.

During the 1950s and 1960s, however, the Innu were pressured into settling in fixed communities by the Canadian government and the Catholic church. Dispossession from the place they call ‘Nitassinan’ has resulted in unemployment, chronic health problems such as diabetes and record levels of suicide and petrol sniffing amongst Innu children.

Asked to describe growing up in the settlements, young Innu time and again reply, It makes us feel ashamed of being Innu.

(Image shows Innu children, Davis Inlet, Canada).

© Dominick Tyler

Solvent abuse is also a serious problem among Innu children and teenagers, and obesity and diabetes are also rife.

Innu children between the age of 10 and 18 are now being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes,

a western disease that only developed after the Innu were pressured into settling in fixed communities. Type 2 diabetes was once largely a risk factor for the 40+ age group; many Innu youth are diagnosed in their early twenties.

Medical experts believe that young people with type 2 diabetes have double the risk of dying compared with type 1 diabetes and after a much shorter duration.

When I was a kid, 15 years ago, there was zero diabetes and cancer. Our grandparents were hunting and eating healthy country foods, says Michel Andrew, an Innu man from Sheshatshiu.

Diabetes has reached epidemic proportions in indigenous communities and places the very existence of these communities at risk, says Professor Jean Claude Mbanya, President of the International Diabetes Federation.

© Dominick Tyler

The Penan, in the Malaysian state of Sarawak, have had the forests they rely on destroyed by logging, oil palm plantations and dams.

Teenage Penan schoolgirls have been raped and sexually abused by logging company workers. This often occurred when transporting the girls back from schools many miles from their homes.

In November 2013 eight Penan, including a 13 year old boy, were arrested for protesting at a dam site and taken in to police custody. Two other Penan, including a boy aged about 16, were arrested when they attempted to visit their relatives at the police station.

© Andy Rain/Survival

A Chakma mother in Bangladesh places her newborn child in a traditional cot called a dhulon, and sings them to sleep with lullabies known as olee daagaanaa.

Since Bangladesh became independent from Pakistan in 1971, the indigenous Jumma people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts in the mountainous south-east region have endured some of the worst human rights violations in Asia.

Gentle, compassionate and religiously tolerant, the Jumma differ ethnically and linguistically from the Bengali majority.

© David Brunetti

Today, the Jumma are also one of the most persecuted tribal peoples.

Sexual brutality against Jumma women and young girls is alarmingly high; rape often goes unreported due to its social stigma.

In the past two months alone there have been at least five reported cases of sexual violence committed by Bengali settlers against Jumma girls. This included the rape of a four year old Chakma girl who was attacked while bathing in a stream.

Little has been done to prosecute the perpetrators of these crimes, said Sophie Grig of Survival International. This leaves Jumma women and girls increasingly vulnerable, as their attackers act with impunity.

© Mark McEvoy/Survival

Most tribal peoples have a long-term view of life; they take into account in their daily decision-making the future health of the environment and the wellbeing of successive generations.

If the lives of today’s tribal children are to be uncorrupted by oppression, exploitation and racism, the governments and corporations that currently violate their rights must adopt similarly sustainable thinking, and look far beyond immediate political or commercial gain.

Tribal issues are being increasingly pushed into political and cultural arenas. But they are still vulnerable, largely because their lands are still coveted. Their urgent need is for people worldwide to join Survival’s movement and help in its unflinching fight for them to be seen as equals.

A world where tribal children are free to live on their own lands in the way they choose is their prerogative. It starts with the recognition of two basic human rights: to land and to self-determination.

We are not here for ourselves. We are here for our children, and the children of our grandchildren.

Bushman, Botswana.

© Survival International

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...