'We are here for our children'

From the green depths of the Amazon to the icy reaches of the Arctic, children raised in tribal communities are taught the skills and values they need to survive.

I grew up a hunter, said Roy Sesana. I cannot read. But I do know how to read the land and animals. All our children could.

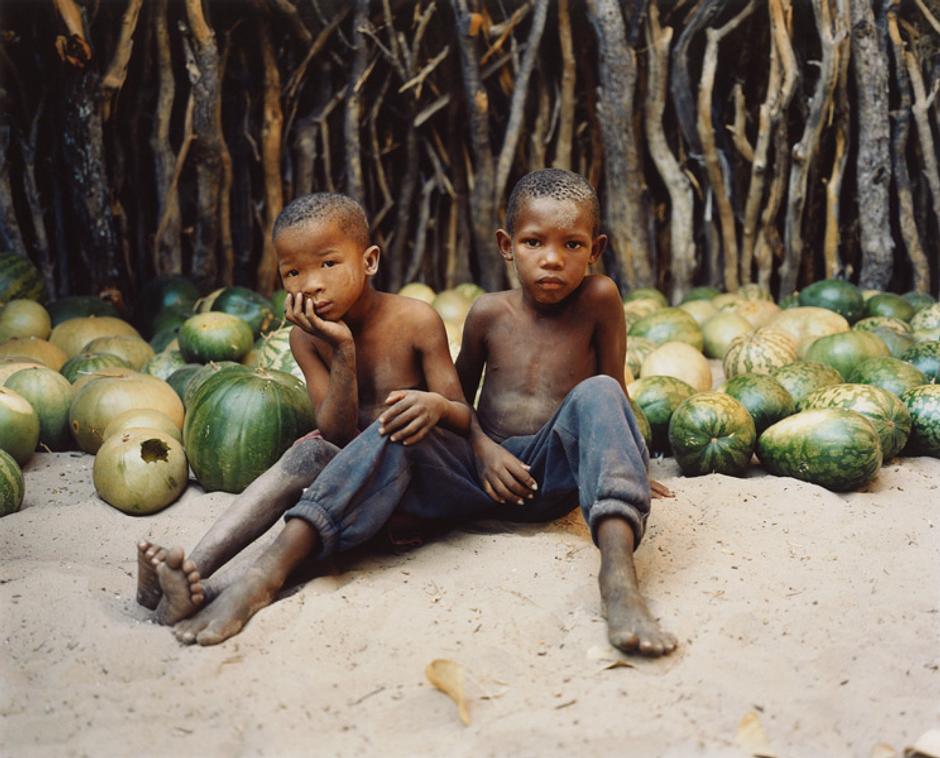

The Bushman peoples are the original inhabitants of Southern Africa. Over thousands of years, they developed hunting practices that have allowed them to provide for the community’s needs without destroying the local environment.

Young boys were given toy bows and arrows to hunt rats and small birds, and how taught to kill spring hare or make blankets from gemsbok skin. Girls as young as five helped their mothers gather plants, berries and tubers. Children learned to be both brave and humble, and were taught that generosity was to be admired and selfishness disliked.

Today, however, after the forced evictions from their hunting grounds in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), many Bushman children live in squalid eviction camps, known to them as ‘places of death’, where AIDS is rife, and where a life devoid of hunting and long-established rituals foments depression and alcoholism. We feel like bits of rubbish put in the waste bin said one Bushman.

Unless the Bushmen are allowed to return unimpeded to their ancestral lands, their children will not inherit the unique ways of life of their great-grandparents, but a life of dependency, despair and ill-health. A significant step towards their full return to their ancestral lands was made recently, when some Bushmen celebrated drinking water from the Mothomelo borehole in the CKGR for the first time since it was capped in 2002.

(Image shows Bushman boys).

© Lottie Davies/Survival

The Moken are a semi-nomadic Austronesian people, who live in the Mergui Archipelago in the Andaman Sea.

Like other tribal children, the Moken young learn to ‘read’ nature through experience and observation. They have developed the unique ability to focus underwater, using their visual skills to dive for food on the sea floor. The Moken are born, live and die on their boats, and the umbilical cords of their children plunge into the sea recounts a Moken myth. Another suggests that Moken children learn to swim long before they can walk.

Their semi-nomadic numbers have diminished in recent years due to political and post-tsunami regulations, companies drilling for oil off-shore and governments seizing their lands for tourism development and industrial fishing. Many have had no choice but to settle in on-shore villages. Losing their ways of life is thus making it increasingly difficult for adults to pass on centuries-old rituals and skills to children.

This generation no longer knows how to make boats, says Hook Suriyan Katale, a Moken man from the Surin Islands, speaking about the ‘kabang’, the Moken’s wooden boat. Today there are only three or four people left who know our ancient craft.

(Image shows Moken children in the Surin Islands, Thailand).

© Andrew Testa / www.andrewtesta.co.uk

Under a charcoal sky, among the grasses and thorn trees of Ethiopia’s Omo Valley, a boy from the Bodi tribe carries his goat.

The tribes that live along the lower reaches of the Omo river have developed agricultural practices that are intricately adapted to the flooding cycles of the Omo, using the rich silt left along the river banks by receding waters to grow a variety of crops. Boys tend to livestock from an early age – Bodi children learn poems that they sing to their favourite cows – and girls help to cultivate staple foods such as sorghum, maize and pumpkins.

The life-giving river is now threatened by government-sanctioned development schemes, including Africa’s largest hydro-electric dam, which will leave the tribes without the annual floodwaters to grow their crops.

The people are hungry, said a man from the Mursi tribe. There is no singing now. The kids are quiet.

(Image shows a Bodi boy, Ethiopia. Joey L cards available from Survival’s shop at http://shop.survivalinternational.org/products/joey-l-greetings-cards)

© J

Sarawak’s rainforest in Borneo is one of the most biologically rich rainforests on earth, and home to the Penan people.

The Penan have long lived in harmony with their forest and its rare orchids, fast-flowing rivers and twisting networks of limestone caves. We were born to live in the forest, they say. It is their home, their history, their supermarket and their pharmacy.

Since the 1970s, however, their ancestral lands have been bulldozed and burned for large-scale logging, oil-palm plantations, gas pipelines and hydroelectric dams. The steep-sided valleys that were once filled with the cries of birds and the song of cicadas now resound with the noise of trucks and falling trees. The forests are being cleared at a rate twice that of the Amazon.

As a result, the Penan’s way of life is being eroded; until the 1960s, almost all Penan lived as nomads, moving camp frequently in search of boar, wild fruit trees and sago palms. Today, many of the 10-12,000 Penan have settled in riverside communities, where malnutrition, disease and illiteracy are common, although the rainforest is still fundamental to the lives of settled and nomadic Penan alike.

The children of the Penan potentially face a destitute future, unless the Malaysian government puts a halt to all development on their land that is carried out without the tribe’s consent.

(Image shows Penan girl with leaf boat, Sarawak, Malaysia).

© Andy Rain/Survival

In those days my mother always took me with her into the forest, said Davi Kopenawa, a Yanomami spokesman from Brazil. There, we would look for crabs, fish with timbó, or gather wild fruits. This was how I grew up in the forest.

Yanomami boys learn to ‘read’ the spoor of animals, use plant sap as poisons and shin up trees by tying their feet together with liana vines; young girls help their mothers cultivate crops such as manioc in their gardens, carry water from the rivers and cook in the communal ‘yano’. All children are taught that sharing is a fundamental tenet of social life and community decisions are made by consensus.

Today, hundreds of gold-miners are working illegally on Yanomami land, transmitting malaria and polluting the rivers and forest with mercury. Davi Kopenawa is fighting for his people’s rights; his vision is for Yanomami children to grow up untouched by diseases brought in by outsiders, in a forest free from industrial pollution.

I want them to be able to see the stars, but not through industrial smoke, he said. I want them to drink the stream-water without falling ill, and wake to the call of the piha bird, instead of miners’ motor pumps.

(Image shows a Yanomami child, Brazil).

© Claudia Andujar/Survival

For the Guarani people of Brazil, land is a precious gift from the great father.

Today, however, the endless deforestation of Mato Grosso do Sul in southern Brazil has turned their ancestral lands into a dry, treeless region of cattle ranches, soya fields and sugar cane plantations.

Many Guarani now live in appalling conditions in overcrowded reserves or make-shift camps on roadsides. As they have lost almost all their forest in the past 100 years, leaving them with very little land on which to cultivate crops, their children have been suffering from malnutrition. A 2008 report revealed that 80 Guarani children had died as a result of malnutrition alone in the previous 5 years.

Many children are suffering, said a Guarani health agent. I want the children to be as they were before, when all was OK. An improvement in the lives of the Guarani starts with the Brazilian government ending the wholesale destruction of the Indians’ land.

(Image shows Guarani children, Brazil).

© João Ripper/Survival

They move through the Amazon rainforest at night, carrying torches made from resin. They are the Awá people, and are one of only two nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes left in Brazil.

Today the Awá are increasingly threatened by loggers, settlers and cattle ranchers. Satellite maps show that over 30% of the rainforest in one of their territories has been destroyed.

As they still depend on the forest for every aspect of their lives – food, shelter and spiritual well-being – their children’s lives are seriously endangered by the destruction of their homelands. The loggers cut down the trees, and all the game runs away, said an Awá man. Without the forest, we are nobody and have no way of surviving.

(Image shows Awá-Guajá child with monkey, Brazil).

© Domenico Pugliese

North-east Canada is a sub-arctic expanse of tundra, lakes and forests. Until the second half of the 20th century, the Innu people lived here as nomadic hunters, relying largely on the herds of caribou which migrate through their land every spring and autumn.

During the 1950s and 1960s, however, the Innu were pressured into settling in fixed communities by the Canadian government and the Catholic church. Dispossession from the place they call ‘Nitassinan’ has resulted in unemployment, chronic health problems such as diabetes and record levels of suicide and petrol sniffing amongst Innu children.

Asked to describe growing up in the settlements, young Innu time and again reply, It makes us feel ashamed of being Innu.

(Image shows Innu children, Davis Inlet, Canada).

© Dominick Tyler

To be a Dongria Kondh is to live in the Niyamgiri Hills in Orissa state, India. But the mountain that the Dongria revere as a god is under threat from mining companies who are eyeing the $2billion deposit of bauxite that lies beneath.

Niyamgiri has always provided physical and spiritual sustenance for the Dongria. To lose their lands to open pit mining would be to lose their livelihoods and unique identity as a people, for the extraction would destroy the forests and disrupt the rivers. “We are mountain people. If we go somewhere else, we will die,” they say.

In 2014 the Dongria won a David and Goliath battle against mining on their hills, but those who resisted the mine are still facing a violent police campaign of harassment and intimidation.

“Where will we children go? How will we survive?” asked a young Dongria Kondh boy when contemplating the possibility of having to leave his home. “No, we won’t give it up. We won’t give up our mountain!”

(Image shows Dongria Kondh boy, Orissa, India).

© Jason Taylor/Survival

Most tribal peoples have a long-term view of life; they take into account in their daily decision-making the future health of the environment and the wellbeing of successive generations.

If the lives of today’s tribal children are to be uncorrupted by oppression, exploitation and racism, the governments and corporations that currently violate their rights must adopt similarly sustainable thinking, and look far beyond immediate political or commercial gain.

Recent successes – such as the reopening of the Bushman water hole in Botswana and the Dongria Kondh’s victory over Vedanta in India – show that tribal issues are being increasingly pushed into political and cultural arenas. But there is a long way to go. Tribes are still vulnerable, largely because their lands are still coveted. Their urgent need is for people worldwide to join Survival’s movement and help in its unflinching fight for them to be seen as equals.

A world where tribal children are free to live on their own lands in the way they choose is their prerogative. And it starts with the recognition of two basic human rights: to land and to self-determination.

Think not forever of yourselves, o Chiefs,

Nor of your own generation

Think of continuing generations of our families,

Think of our grandchildren

And those yet unborn,

Whose faces are coming from

beneath the ground

(Quote by Peacemaker, Iroquois Confederacy, USA

Image shows Aborigine children at play, Pitjantjatjara, Australia)

© Alastair McNaughton/www.desertimages.com.au

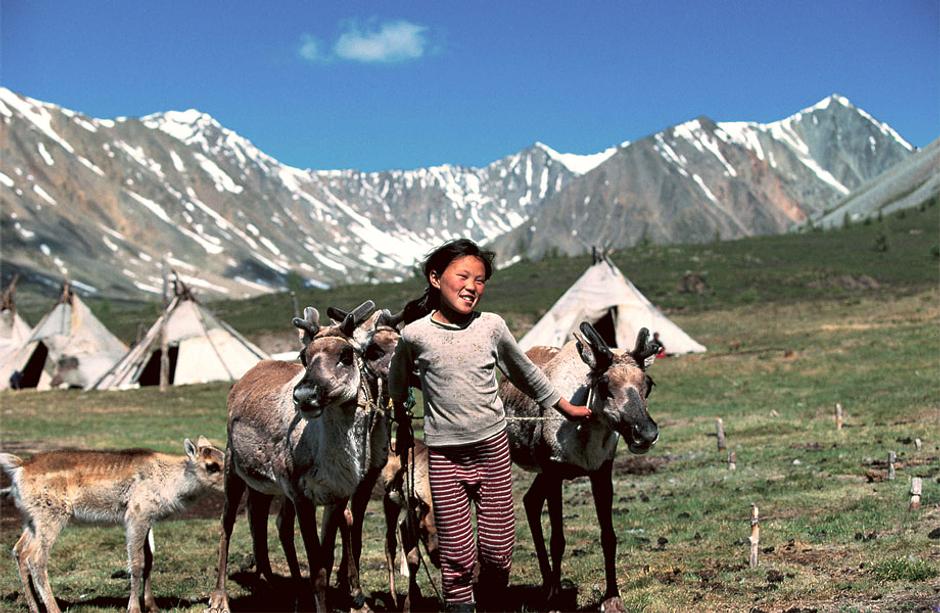

In Malaysia, Penan children help to build homes from tree saplings and giant palm leaves; beneath the blue-green surface of the the Andaman Sea, Moken children learn to catch dugong, crab and sea-cucumber with long harpoons; in Mongolia, Tsaatan children are taught the ancient herding skills of their parents by corralling reindeer on the grasslands.

Tribal children are the inheritors of their territories, languages and unique ways of seeing the world; human repositories of their ancestors’ knowledge.

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...