The Racist, Colonial Dynamic at the Heart of African Conservation Policy

© Gianalberto Zanoletti/Survival

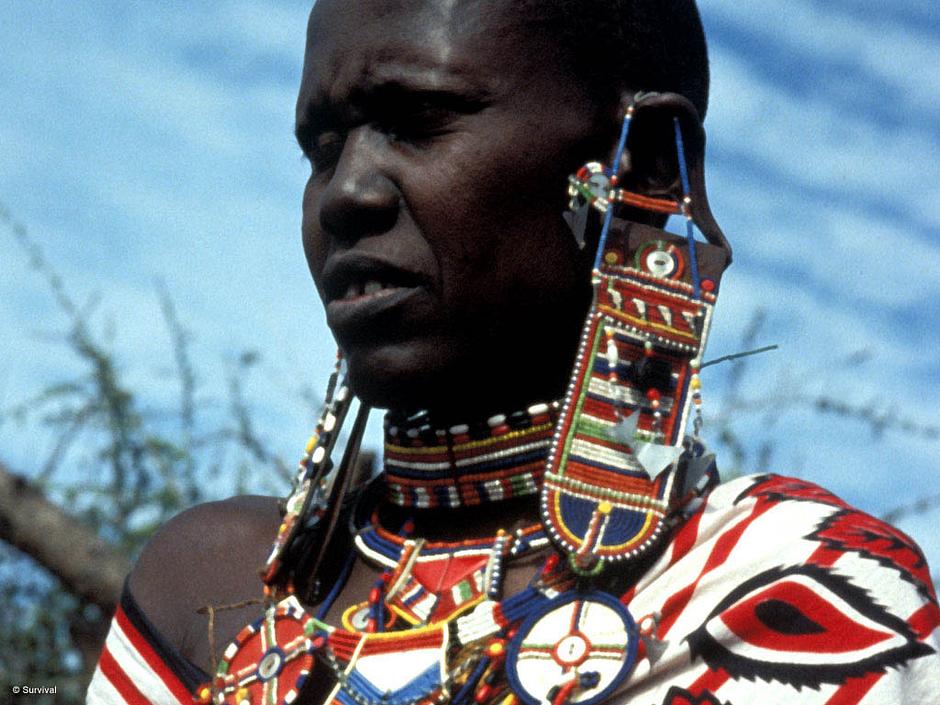

© Gianalberto Zanoletti/SurvivalMordecai Ogada was sitting in a luxury safari lodge, admiring the view of Kilimanjaro. He could see many of Africa’s most iconic species: giraffe, water buffalo, even a few elephants far in the distance. As a professional conservationist, with a PhD in carnivore ecology, the sight was both familiar and pleasing. He was being treated like a tourist. Someone came in and offered him a cocktail. Then, one of his white hosts and sponsors, the people whose largesse he was enjoying, said:

“We’re going to have to move that Maasai village. It’s spoiling the view for tourists.”

For Dr. Ogada, this was a decisive moment. “I was a qualified black face, put in place to smooth over fifty years of exploitation.”

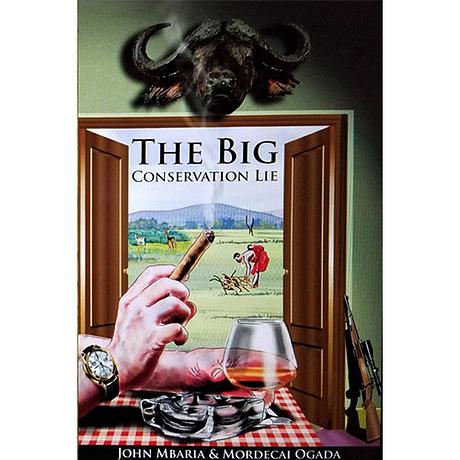

In “The Big Conservation Lie,” Dr. Ogada and fellow Kenyan, journalist John Mbaria, present a powerful challenge to the prevailing conservation narrative. Written by people who are actually from one of big conservation’s key target countries, it dismantles many of the environmental movement’s most troubling myths: the pristine wilderness “untouched by human hands” until European arrival; the supposed lack of interest or expertise in wildlife among native conservationists and communities; the idea that brutal poaching would be endemic without foreign intervention, and so on.

Ogada and Mbaria sum up the essence of their argument early on: “The wildlife conservation narrative in Kenya, as well as much of Africa, is thoroughly intertwined with colonialism, virulent racism, deliberate exclusion of the natives, veiled bribery, unsurpassed deceit, a conservation cult subscribed to by huge numbers of people in the West, and severe exploitation of the same wilderness conservationists have constantly claimed they are out to preserve.”

To colonizers, Africa is and always has been a “wild and uncontrollable environment” – home to “charismatic” species that can be admired (or shot) from afar. The conventional narrative has generally suggested that only European and American expertise can tame or protect it. The authors argue that this has given western NGOs such as the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) enormous power.

It has also created space for white “saviors” (and the “saviors” are always white), such as George Adamson, Jane Goodall, and Iain Douglas-Hamilton, to step in and be seen to make the decisive difference. There’s no place for Africans in the picture.

© Lens&Pens Publishing

© Lens&Pens Publishing

Ogada and Mbaria take aim at some of conservation’s most sacred cows. George Adamson, for example, the white British subject of the 1966 film “Born Free” is exposed as a chancer, a failed businessman who accepted conservation donations, despite being a trophy hunter with next to no conservation expertise.

Much of the authors’ scorn is reserved for the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS). Though it presents itself as a conservation organization, the true face of this “service” is revealed. It is composed mostly of retired soldiers and mercenaries, heavily armed and organized much like a militia. Run for many years by Richard Leakey, a wealthy white Kenyan of British descent, it is accused of corruption, violence, and perpetuating the appropriation of some of Kenya’s most fertile areas by the British colonials and their descendants.

As the authors point out, the KWS receives funding, equipment, and training from western powers, including the United States and Great Britain. This doesn’t stop if from profiting from the land it supposedly exists to protect, through tourism, and even ties to big mining and pharmaceutical companies. It is revealed to have cut deals with the German corporation Bayer, and some of its most senior figures have themselves been implicated in wildlife crime, including ivory trafficking. Despite this, they and the armed operatives they command are considered “above suspicion” by the Kenyan authorities.

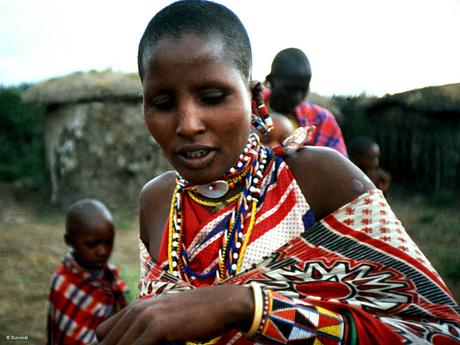

Similarly, they expose the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), one of the best-respected of the big conservation organizations, for having supported a project which involved evicting thousands of Maasai people from forests which they’d been dependent on and managed for millennia. This is despite the fact that the Loita woodland that they were removed from was largely intact at the time, whereas areas of forest which had been in western hands for decades had badly deteriorated. This is typical of the “externally-defined agenda for social development” which the authors critique, and which often doesn’t involve much effective conservation.

Many western conservation charities, it’s argued, exist primarily to secure publicity for their founders. A recent example is “Space for Giants” – an initiative founded by Russian oligarch Evgeny Lebedev. The organization has released several high profile op-eds and photos showing “action” in the name of conservation, but has, according to the authors, done little on the ground, beyond charging over $5,000 a head (plus mandatory donation) for luxury safari tours.

What a lot of western-initiated conservation boils down to, according to Ogada and Mbaria, is “surveillance of vast areas with huge mineral potential under the guise of wildlife conservation.” In place of this neocolonial approach, they advocate closer partnerships with local and tribal communities, respecting and using the extraordinary, but unacknowledged, expertise about the natural world that already exists in large parts of Kenya and the wider world.

There are plenty of Africans working in conservation, but they get very little recognition for their work. Professionals like Dr. Ogada are not only experts in their field, but also provide a different perspective on the deeply flawed western approach to conservation, an approach which has failed, even on its own terms.

Likewise, there are millions of people across Africa who live largely sustainable lives and have plenty of insights to offer, if only western conservationists would be willing to step aside and put them at the forefront of the environmental movement. Only by listening to Africa’s tribal peoples – the best conservationists and guardians of the natural world – will we stand any chance of protecting the natural environment. “The Big Conservation Lie” is highly recommended for anyone interested in this struggle, or in debunking the pervasive myths that are holding the environmental movement back. It is a bold and important book that deserves your attention.

Lewis Evans is a campaigner at Survival International.

AUGUST 4, 2017