Blood Carbon: how a carbon offset scheme makes millions from Indigenous land in Northern Kenya

© Survival

© Survivalby Simon Counsell, independent researcher and writer

Executive summary

Research by Simon Counsell and Survival International into a carbon offset scheme on Indigenous land in northern Kenya raises major questions about the credibility of the project's claims, as well as about the potential impact on the rights and livelihoods of the Indigenous pastoralist peoples to whom this land is home. To read the full report, click here.

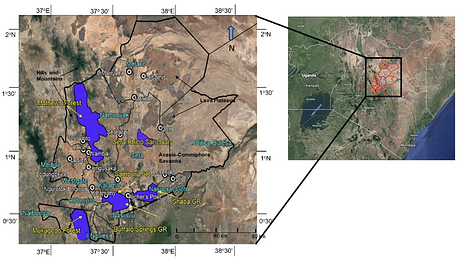

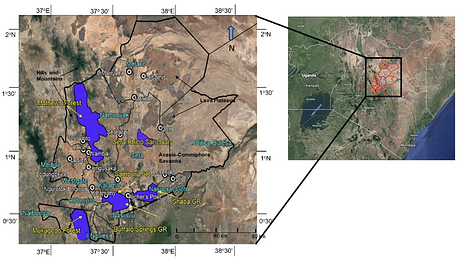

The Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT) claims that its Northern Kenya Grassland Carbon Project (NKCP) is “the world's largest soil carbon removal project to date and the first project generating carbon credits reliant on modified livestock grazing practices”. The project covers half of the four million hectares now included within NRT’s grouping of ‘Conservancies’ – areas which are notionally being managed for the benefit of wildlife as well as local people. Thirteen more-or-less contiguous conservancies are involved in the project (see map, Figure 1).

Figure 1: The project location

© Survival

© Survival

Note that the area outlined in red on the right hand map, which is generated using a shapefile provided by the project, appears to include some conservancies in the north which have not been part of the carbon project to date.

The area has more than 100,000 inhabitants, including indigenous Samburu, Maasai, Borana, and Rendille people. All are pastoralists, whose way of life is inseperably bound up with their livestock – principally cattle, but also camels, sheep and goats. Grazing typically follows local and regional rainfall, sometimes involving migration routes that may extend hundreds of kilometers. Grazing patterns are traditionally dictated by elders according to long-standing sets of rules, allowances and sanctions.

The project, which started in January 2013, is based on the notion that replacing what it calls the traditional ‘unplanned’ grazing with ‘planned rotational grazing’ will allow vegetation in the area to (re)grow more prolifically. This in turn, the project claims, would result in greater storage of carbon in the conservancies’ soils - averaging around three-quarters of a tonne of additional carbon per hectare per year. Thus the project would allegedly generate around 1.5 millions of tonnes of extra carbon ‘storage’ per year, producing around 41 million net tonnes of carbon credits for sale over a 30-year project period. The gross value of these could be around US$300 million – US$500 million, but potentially much more.

It is Project #1468 in the Verra registry. The Verra system is supposed to ensure that carbon offset projects generate real, credible and permanent emissions reductions. Verra says that it uses a “rigorous set of rules and requirements” to verify that emissions reductions (or additional carbon storage) are “actually occurring”.

The project is an example of a so-called ‘nature-based solution’, wherein conservation programmes are funded through the sale of carbon credits to polluting companies, generating extra revenue to both expand and intensify the preservation or ‘restoration’ of land for wildlife. The project has been described by the European Commission as the model on which is intends to base a forthcoming large funding programme for conservation projects in Africa called ‘NaturAfrica’.

In its first crediting period (2013-2016), the project generated 3.2 million carbon credits. By January 2022, all of these had been sold. The exact total gross value of these sales is not known, but is likely to have been between US$21 million and US$45 million. Most were sold in large blocks, including 180,000 to Netflix and 90,000 to Meta Platforms (formerly Facebook). A second batch of credits, for 2017-2020, was claimed by the project in April 2022; although no verification report of these had been published by the end of January 2023, another 3.5 million credits were verified, and the credits started to be issued in December 2022. By February 2023, 1,3 million of these had been sold, mostly again in very large (and anonymous) blocks.

This assessment of the Northern Kenya Grassland Carbon Project raises many questions about the credibility of the offsets being generated as well as the likely impact of it on the area’s indigenous peoples. The report finds that:

- Impacts on communities: The project relies on major changes to the way in which the area’s indigenous pastoralists graze their animals – breaking down the long-standing traditional systems of gada and mpaka, for example, exercised respectively by the Borana and Samburu people, and replacing them with a collectivized, centrally controlled system more akin to commercial ranching. As well as being culturally destructive, this could also serve to endanger livelihoods and food security, by requiring livestock to remain inside the project area and disrupting or preventing migrations following rains during seasonal droughts (which are worsening).

- Additionality: The project does not present a credible case for its carbon additionality. It is based on a presumption that the traditional forms of grazing were causing degradation of soils and that only the carbon project could remedy this. But the case that the area was being degraded through ‘unplanned grazing’ is not supported with any empirical evidence, and indeed the project ignores that the ‘unplanned grazing’ is in fact subject to traditional forms of governance which have sustained pastoralism within broadly sustainable limits for many centuries.

Rather than showing that the project was additional because there was no other way of financing the intended changes to grazing regimes, it chose to show that its additionality lay in the fact that there were many barriers to achieving what was wanted by the project, and that it was least like what had had happened in the past. This method of demonstrating additionality has the highly perverse effect of incentivising an approach (centralized, rigidly planned grazing within prescribed geographical areas) that is in fact strongly both contrary to the cultural norms of the areas’ indigenous pastoralists, and also potentially highly dangerous to people and the environment.

There is no empirical evidence drawn from direct assessment or data that the project’s purported ‘planned rotational grazing’ is either a/ actually occurring across most of the project area or b/ actually any better for soil carbon accumulation than the traditional pattern of pastoralist land management. On the other hand, there is evidence that prevalent traditional grazing is not strongly correlated with either vegetation changes or the variable levels of soil carbon. - Baselines: As with additionality, the baseline for the project (i.e, what is claimed would have happened in the project’s absence) is merely drawn from a presumption that the traditional forms of grazing are causing degradation of soils, and would continue to do so, without this being based on any empirical evidence. The limited information provided by the project purporting to show a decline in vegetation quality prior to the project does not in fact show this at all. Evidence presented by NRT indicates that, if anything, the quality of vegetation has declined since the project started; if, as the project asserts, vegetation cover is correlated with soil carbon, this would suggest that soil carbon in much of the area is in fact also declining.

- Leakage: There are major issues with carbon ‘leakage’ from the project, particularly in the form of livestock moving off-project. The project purports to be able to quantify how many ‘livestock days’ are spent out of the project area, but analysis of the monitoring data on which these claims are based – especially the monthly grazing reports – show that these are for the most part wholly inadequate for such a purpose. Many are entirely lacking in credible information about where livestock are at any given point in time, with little or no information about where large number of livestock have moved to. The quantification of leakage is in fact little more than guesswork.

Related to this issue, it is clear from both the livestock reports and other project documentation, that the project has no meaningful control over its boundaries, which is in fundamental non-compliance with the methodology (VM00032) under which the project was developed. The validation and previous verification audits scrutinized this issue but wrongly accepted the project’s reassurances that it has mechanisms to detect and monitor movements of livestock off-project. In reality, as interviews with residents during a site visit by the author in 2022 confirmed, there is no such mechanism; the 1,000-kilometre project boundary is highly porous, and almost impossible to monitor in any meaningful way. Even though it proved impossible for the project to demonstrate that it complied with this most basic eligibility conditions to be a VCS carbon offset project, it was nevertheless both validated and verified, and the eligibility question was simply delayed to some future time and for a later verifier to deal with.

The containment of livestock within proscribed boundaries is, as the project itself admits, anyway contrary to the long-established traditional grazing patterns which can include short- and long-term, long-distance migrations. These can be essential for survival of both livestock and people, especially during times of drought. - Project monitoring: Some of the issues above are related to the project’s fundamental inability to monitor key aspects of the purported implementation of planned rotational grazing. Some of the calculations used to estimate the project’s claimed additional storage of carbon were based on monitoring information that was entirely unfit for the purpose. The critically important periodic reports on grazing activities submitted by each of the 13 participating conservancies (which were available to the first verification period’s verifiers) are generally extremely poor in quality. They lack essential or credible information about the numbers of animals present, their location, and their movements. For the periods of both the first and second verification, the grazing reports and maps are almost entirely worthless as a means of assessing even whether ‘planned rotational grazing’ has been implemented, let alone its outcomes. They indicate very strongly that the project could not properly monitor its boundaries, let alone control them. They strongly contradict the project’s claim that leakage of livestock out of the project area was ‘negligible’. They strongly suggest that the project was not complying with the methodology requirement to be able to control its boundaries, even if the appearance of being able to monitor them improved slightly in recent years. They strongly suggest that the evidence necessary to demonstrate that ‘Bunched Herd Planned Rotational grazing’ was actually taking place was largely lacking.

More widely, the project depends entirely on remote sensing of proxy indicators of soil carbon (i.e, an index of vegetation cover) rather than direct measurement of soil carbon, and then manipulation of that data through further algorithms/models. The steps involved in this, on the project’s admission, contain very large margins of error and inaccuracy. There are very strong reasons to question whether the grazing reports being generated by the project could be correlated with the vegetation change maps derived from satellite images.

Inspection of the originals of the livestock maps (rather than the barely intelligible small versions shown in the project monitoring report), shows enormous and important discrepancies compared to the satellite-derived vegetation maps. - Permanence: Even if the project were actually resulting in any real additional storage of carbon in the project area’s soil – which is at best highly questionable - it is doubtful that it will remain there for very long. All the data points to long-term climate-related changes in weather patterns, and particular increased length and severity of droughts, across most of the project area. This will result in declines in vegetation and soil carbon storage. Although the project in principle acknowledges this, it dismisses such concerns by pointing to some hoped-for increases in grazing availability due to the project’s own activities. However, there is no empirical evidence presented to suggest that these have had any sustained success or can in any way compensate for the long-term negative effects of climate change.

- Consultation, free prior and informed consent, and grievances: To date (including the Second Monitoring Report) there is wholly unconvincing evidence presented that NRT has properly informed communities about the project, let alone received their free prior and informed consent to it. We note that this was a matter of concern in both the validation and first period verification, and that the concerns about this largely remained unresolved. Provision of information about the project has, at best, been limited to a very small numbers of people, mostly those associated with Conservancy bodies (such as the Boards), and for the most part only long after the project had already advanced. There is no evidence that adequate information was provided in Kiswahili, Samburu, or other local languages. The project’s response to the auditors’ questions about consultation during the first verification assessment suggests that there was almost no meaningful provision of information – and hence no possibility of obtaining any form of consent. The same applies to the years 2017-2020 as covered in the second verification period. It is clear from our own investigations that, to date, very few people in the project area – including even those on the Boards of Conservancies – have a clear understanding of what the project is about, nor their roles, responsibilities and supposed benefits from it.

Contrary to Verra’s current requirements, there is no mechanism for grievances over the project (as opposed to employment grievances, as referred to by NRT in the Project Document). NRT may not, as they claim, have received any complaints during the second verification period, but this could simply be because a/ almost no-one knew of the project during that period and b/ there was no complaint mechanism. There have certainly been serious complaints recently, including at least one conservancy formally withdrawing from the project. - Legal basis of the project: There are very serious issues relating to the legal basis of the project and the way it has been implemented. At least half of the project area consists of Trust Lands, which are subject to the terms of the Community Lands Act (CLA) 2016. This places responsibilities and obligations on any bodies seeking to carry out activities on Trust Lands, and mandates a central role for County governments in holding the lands in trust until such time as they are formally registered by communities. As yet, none of the Trust lands in the project area have been registered (and community members believe that NRT is obstructing their land registration claims). There is no evidence that NRT has complied with various important requirements of the Community Land Act 2016 in its implementation of the carbon project. The very legal basis of the establishment by NRT of conservancies in Trust Lands has been challenged through a constitutional petition presented on behalf of communities within the carbon project area, and others, at the Isiolo Environment and Land Court in September 2021, a case which is still in process.

- The basis of NRT’s rights to ‘own’ and trade carbon from the respective lands: In addition to questions about the legality of some of the Conservancies, and apparent non-compliances with the CLA, there are serious doubts about the basis on which NRT has obtained the rights to trade the carbon putatively stored in the soils of the Conservancies. A formal agreement to this effect was not signed between NRT and the Conservancies until June 2021 – eight and half year after the project started, and entirely after the period covered by first and second verifications. In other words, even setting aside (non-) compliance with the CLA 2016, NRT did not have a clear contractual right to sell the carbon during this period.

- Distribution of benefits, and outcomes: We have serious concerns about how the funds generated through carbon sales are being distributed. Whilst the project claims that the 30% of the total funds to be distributed to the Conservancies are for purposes which the ‘communities’ themselves determine, this largely proves not to be the case. 20% of the Conservancies’ portion has to be spent on NRT’s prescribed grazing practices (which, as above, is contrary to cultural norms) and rangers. Another 20% is distributed to conservancies for purposes which have not been specified. The remaining 60% of the Conservancies’ portion of the funds is distributed at the discretion of NRT, through a largely opaque process, which community leaders in the project area believe is used to exert control over communities and to promote NRT’s own priorities.

- The project’s validation and verification: Far from having undergone “rigorous” assessment, numerous fundamental problems with the project were not properly addressed during its validation and the subsequent verification of its first claimed 3.2 million tonnes of carbon storage.

Conclusion

NRT has not provided any convincing evidence that they properly informed communities about the project, let alone received their free prior and informed consent to it. It is clear from our own investigations that, to date, very few people in the project area have a clear understanding of what the project is about, nor their roles, responsibilities and supposed benefits from it.

The basic premise of the project, that it can enforce ‘planned rotational grazing’ within specified geographical areas runs fundamentally against the traditional indigenous pastoralism of the area, is conceptually seriously misguided, potentially dangerous and probably doomed to fail. It is based on a long colonial prejudice that sees pastoralists as incapable of managing their own environment and constantly destroying it by overgrazing. We believe that the project’s claim to be permanently storing quantifiable amounts of additional carbon in the soils of northern Kenya is highly implausible. We believe that the project has no solid basis of additionality, lacks a credible baseline, and suffers from unquantifiable leakage. The project has not empirically demonstrated that it is actually achieving any real additional soil carbon storage. The project’s legal basis, including whether NRT has the right to obtain some or all of the traded carbon, and compliance with applicable laws, especially the Community Lands Act 2016, are highly questionable. One of the implications of this is that project funds so far retained by NRT should probably have reverted to the relevant communities.

Survival International © March 2023

To read the full report, click here.