Of Tigers and Men — the shocking truth about tiger conservation

By Fiore Longo, Research and Advocacy Officer

July 27, 2018

Is destroying the lives, lifestyles and livelihoods of so many human beings really the best possible solution to the tiger’s problems?

We were all sat still around the fire. It flickered across the grey concrete walls behind us. Here with the Baiga people on behalf of Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples, I was visiting the remains of what was once a community.

“In the forest we had everything: food, clothes, water. When they brought us here we lost everything. Now we have nothing left”.

His far-away gaze lit fleetingly with thoughts of home; the rich jungles of Kanha and the forests that inspired the Jungle Book in Madhya Pradesh, India.

These Baiga people became outcasts from their Eden four years ago, but it wasn’t a snake that got them evicted, it was the tigers.

“People and tigers can live together in the same space” a Baiga man explains to me. “We are the protectors of the forest. If we don’t save it, what will happen? If we abandon it, who will protect it?

The night absorbs his words in cold silence, but his question reverberates. An estimated 100,000 people in India have already been illegally evicted from their homes in the name of tiger conservation, and at least 282,000 more people are currently facing this threat. Is destroying the lives, lifestyles and livelihoods of so many human beings really the best possible solution to the tiger’s problems?

Big money for big cats

Tigers are listed as a threatened species on the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). In 1900, it is estimated, they numbered around 40,000 in India, and by the end of the colonial period they had been reduced to 5,000. Today, it seems that there are only 2,226 remaining.

To save its “national animal”, the Indian government launched Project Tiger in 1973. This is now run by the National Tiger Conservation Authority and is supported by large conservation organizations. A fundamental tenet of its rescue strategy is “making room for nature”. Conservationists argue that to guarantee the survival of India’s tigers, the animals need huge areas of land all to themselves: no people allowed.

Tigers are also under threat from the loss of their habitats due to industrialization, urbanization and road building, but the most obviously dramatic danger is illegal hunting, driven by demand from the increasingly wealthy Asian market. According to an inquiry carried out by award-winning journalist Wilfried Huismann, in New York’s Chinatown the price of tiger bonemeal tea (sold as a male potency potion) exceeds that of heroin.

Concern about tiger numbers and grizzly photos of trafficked body parts readily convince western donors to dig deep and show support for big conservation groups like the Word Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) who are supporting tiger conservation in India. The Indian conservation model is to legally map out protected conservation zones and patrol their boundaries with guards, who, in some reserves, are armed and can be authorized to shoot on sight. Money donated by the tiger-loving public is used to train and equip these guards. This is known as “fortress conservation”.

Every year, enormous amounts of money from well-intentioned individuals flow easily into the coffers of these large conservation organizations; WWF alone has a daily income of $2 million. Even if you are the kind of person who is prepared to set aside the devastating impact on thousands of tribal people’s lives, is the environment really best served by the brutal eviction of its best guardians, the self-identified “protectors of the forest”?

The Evidence

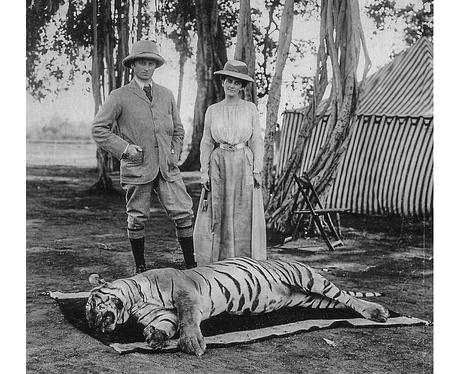

You won’t even need to look again at the figures above; you worked it out the first time. The greatest reduction in tiger numbers occurred during the colonial period. Tiger hunting was a common sport among the British and Indian elite during the British Raj. Prince Philip himself, former President of both the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) UK and International, has at least once participated in such a hunting trip. It was these bloody excursions which were responsible for the devastating decline of the tiger in India, not the local tribes.

© Wikimedia

© Wikimedia

Consider then the fact that 40% of Indian tigers live outside reserves; building sporadic “conservation fortresses” is an incomplete solution. Should we just let tigers go extinct outside the patrolled perimeters and the natural landscape there wither away too? Local tribal lifestyles have evolved hand in hand with this landscape and its wildlife. Listening to the lived experience of the inhabitants of that environment and working with them to protect the forests is a far better (and cheaper) solution than driving them out and making them the enemies of conservation.

But to really combat poaching and strike at the heart of the problem, it’s essential to think beyond the simple walls of fortress conservation and question the sinister economics that drive the black market. Organizations like TRAFFIC (the wildlife trade monitoring network), are now recognizing that to combat the illegal wildlife trade it is critical to also focus on the consumers of these stolen body parts. Efforts and money could likely both be better invested in projects that aim to change buyers’ attitudes and reduce demand. As long as someone’s willing to pay the kind of exorbitant sums which incentivize desperate people to risk their lives, both sides of the law profit handsomely from fortress conservation.

Last year’s BBC documentary, Killing for Conservation, showed that the armed park rangers in India’s Kaziranga National Park are no deterrent to illegal hunters. People are ready to put their lives at risk for the high prices generated by the high stakes; the very stakes erected to keep them out. At the top of the chain, king-pin criminals collude with corrupt officials with impunity. The BBC reported that at one stage the park rangers were killing an average of two people every month — more than 20 people a year; in 2015 more people were shot dead by park guards than rhinos were killed by poachers. Innocent tribal people, including a severely disabled man searching for his cattle, have been killed by guards.

This does not make for easy reading. Yet evidence proves again and again that Indigenous peoples manage their environment and its wildlife better than anyone else. Since 1969, Survival International has been helping them make their case on the world stage, and I was here in India not only to challenge the idea of fortress conservation as a way to protect the environment, but also to learn more about the grave violations of human rights that are committed in the name of conservation.

Double Standards

The most controversial aspect of the tiger reserves becomes evident as soon as you visit one. While local tribes are illegally evicted and risk beatings, torture and even death if they enter the reserves, hundreds of thousands of tourists are welcomed in, and hotels and restaurants are booming.

© Brian Gratwicke

© Brian Gratwicke

Kaziranga National Park alone was visited by more than 170,000 tourists during the 2016–2017 season. As I travel the windy roads of its breath-taking forests by jeep, I’m not able to hear what the Indian boy beside me is trying to tell me. The noise of our engine alone is deafening, and I count the vehicles that we pass: 16 in just half an hour.

“Tourism and conservation may seem to be polar opposites, but they are complementary to each other. Our main focus is wildlife conservation, and eco-tourism is an intergral part of that,” the field director of the Ranthambore Tiger reserve told the Times of India.

In the Nagarhole reserve, a man from the Jenu Kuruba people tells me his view: “They evicted us on the pretext that we made noise, that we disturbed the forest, but now there are a lot of jeeps and tourism vehicles — isn’t that a disturbance for the animals?”

“The tiger is our brother”

In a documentary made in collaboration with the WCS, a renowned Indian champion of fortress conservation, claims that tribal people are “constantly living in fear of elephants, leopards and tigers.” For the Indian representatives of WCS, convincing Indigenous people to leave their lands is viewed as a generous act; not only towards nature but also a kindness to the Indigenous people themselves. But this is an outsider’s view, and those who were born with the tiger do not fear her.

The Chenchu tribe, whose forest has now been split into two tiger reserves, see the tiger as their big brother and a god. They have lived alongside the wild animals for generations and happily co-exist. A Chenchu leader explained to me in Amrabad Tiger Reserve, “Tigers are like our big brothers, they help us. We are not hunters. We are forest lovers. We take care of cheetahs, wild dogs and tigers. If a tiger eats a forest animal, they will eat one part and they will leave one part for us. When we go to gather food, the birds help us, they tell us if there are any dangerous animals around.”

They explain, in an open letter released on World Tiger Day 2018, “We see the well-being of the forest as our duty; we protect the animals and plants of this wild forest without harming them. This forest is our home.”

I heard the same message from all the tribal people I met, and it was the opposite of WCS’s description of people terrified of wildlife and desperate to leave the forest.

“When we see a tiger, we are not scared!”, a Soliga man explains to me in the BRT Hills Reserve. “For us it’s like livestock, like a cow, or a chicken. We know how to live with them, we’ve done it for millennia. Tigers, elephants… for us there’s no difference. You are the ones that see them in newspapers and are surprised. The animals are part of our lives.” It seems the tigers can’t bear to be “insulted”, another man tells me: “If we come across a tiger we are not scared: even a child knows that calling them “big dogs” is enough to make them go away!”

The last tiger census proves that tigers and tribal peoples can flourish side by side. In the BRT Hills tiger reserve, in which the Soliga people have won the right to remain, the number of tigers has increased well over the national average for the first time in a reserve. In the rest of India tiger numbers have increased by 30% in four years; in the Soliga’s forests the increase was more than double that.

These evictions are not only wrong, they are illegal.

In 2006, the government passed a law that specifically protects the right of tribal peoples on their ancestral land: The Forest Right Act (FRA). Subsequently, the Wildlife Protection Act, the law that regulates the protection of Indian fauna and flora, has been amended to harmonize with this new protection in favour of Indigenous peoples. Indian law states clearly that relocations from tiger reserves can’t take place without the prior, free and informed consent of the tribal peoples who live there.

According to Indian law, in order to conduct a legal relocation, evidence must be provided to demonstrate that the community is irreversibly harming the flora and fauna, and that it’s coexistence with wild animals is impossible. Then, if the community gives its consent, they should be offered one of the two options of the resettlement package that the authorities are obliged by law to provide: either cash (10 lakhs Rs per nuclear family, around 14,500 US dollars), or relocation to a resettlement village.

Take the first option and the community is scattered because each individual family must look for a new home without receiving any type of assistance. In the second, they should have access to a house, a school, a plot of land, drinking water and other services made available by the government in the new settlement. However flawed, the law marked a “step forward” in the protection of the tribal peoples of India.

But this is not what is happening, at all.

I’ve lost count of the evicted villages or villages under threat of eviction that I visited on this trip, taking in numerous reserves across India. Evidence of irreversible damage to nature by tribal peoples has on no occasion been provided. From interviews in the villages, it seems that the authorities have a most peculiar understanding of “consent”: “[Officials] told us we would have to leave and we couldn’t stay there. That village had been our home for generations. They said they would put tigers there, which would come into our house, and elephants, which would come and knock down our homes, so that we wouldn’t be able to live there anymore.”

When threats aren’t made directly, the communities endure so many restrictions that they are forced to leave their lands, chipped down to the bone by small daily violations of their basic rights to live. Gathering fruits and dried branches from the forest is forbidden, as is reconstructing their houses if they have been destroyed by storms. But outside the forest, the situation is even worse.

Those who accept the cash compensation rarely receive the promised sum. Looking for arable land at a fair price can become a herculean struggle, especially for those that have always lived in the forest and are not savvy to transactions on the open market.

In most cases families end up living on the edges of their forest, in complete squalor, without even the comfort of their own community around them. Villages that are moved en masse to relocation sites don’t fare much better. The Baiga evicted from the Achanakmar Tiger Reserve in 2009 exist in limbo between a school perpetually under construction and strips of barren land. Remembering the lush living beauty of their forest amid the grey squalor of these half-finished settlements must weigh on the Baiga like a death sentence.

They knew too much

The Baiga have lost many things, but they still carry their memories proudly. They don’t understand, just like I don’t understand, why they are paying for others’ crimes against nature. How is it possible that an outsider on their ancestors’ land knows it better and knows what should be done with it, while its true owners rot silently by a roadside?

And the tourists. The tourists. The tourists who arrive in droves to see the spectacle of nature as observers. Fee-paying, tour-guided, ticketed and touted, camera-clicking, rubbish-dropping, jeep-squealing tourists. Welcome. Here. Playing their “important role” in protecting the environment. Those big conservation charities many donate to are partnering with industry and tourism, while the best allies of the environment are being destroyed. It’s a con. And it’s harming conservation.

The Baiga people wonder why the authorities are so intent on banishing them from their forest. Sat around the fire they whisper… maybe, as old companions of the forest, they are a nuisance, they know too much and see too much.

© Survival International, 2013

© Survival International, 2013

Their identities are erased. If they want to attend school, it is forbidden to have tribal tattoos or long hair, traditional for Baiga children. They are considered primitive practices by the authorities, but for the Baiga they are simply part of who they are. Now they have been evicted from their forest, their identity lives on in these tattoos.

Far away from the coolness of their trees, an electric light of a bulb illuminates the tattooed faces of the Baiga sat on the ground next to me, amazed that someone wants to hear their story.

“Now that the Baiga can’t have their tattoos, what will accompany them after death?”, I ask. “Nothing”, replies a toothless and lonely man. “Nothing will accompany the Baiga after death.”

These evictions are illegal. They destroy lives. And they won’t save the tiger. It’s time for us all to stand up for those who have protected the tiger and its forests for so long. We need a new model of conservation in India, one that works with, not against tribal people. For tribes, for nature, for all humanity.

__________

More than 150 million men, women and children in over 60 countries live in tribal societies. Find out more about them, the struggles they face, and how you can help – sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.