Killing conservation – the lethal cult of the empty wild

© Chensiyuan/CC BY-SA

© Chensiyuan/CC BY-SABy Stephen Corry

This is the fifth article in former Director Stephen Corry’s series on conservation. For a full list of all articles, please click here.

A version of this article was published by Alternet on January 31, 2017.

Conservation claims to be science-based but was in fact born from beliefs originating in Protestantism, particularly its Calvinist branch. It’s not generally realized that the environmental movement eventually diverged into two doctrines with opposing views about people. One of them incorporates human beings into its vision, but the other, the oldest and most powerful, doesn’t. If they really are to have a chance of contributing to a better world, those who care about the environment must press the big conservation organizations to revoke their founding dogma.

The first white men known to have entered the Yosemite Valley were soldiers from the Mariposa Battalion hunting Native Americans. The tribes were rebelling against the theft of their lands and they had to be contained and pacified to protect the invading “forty-niner” gold diggers. When “negotiations failed, force (was) used to bring the Indians to terms.”1 By the time the militia reached the valley in 1851 the tribespeople had sensibly beaten a tactical retreat, apart from one woman too old to escape. The battalion retaliated by destroying the Indians’ winter food stores.

Three months later the Mariposa War was over and a sort of peace reigned: The Native Americans had either been killed, forced onto reservations, or reduced to conquered and dispossessed remnants.2 Once it had been largely emptied of its original inhabitants, the new invaders characterized Yosemite in religious terms. Prominent Protestant preacher, Thomas Starr King, sermonized about it in 1860 proclaiming, “A passage of scripture is written on every cliff.”3 The same credo was soon promulgated by that son of a preacher, John “of the mountains” Muir (now revered as the father of American environmentalism), who characterized his ascent of Yosemite’s Cathedral Peak as “the first time (he had) been at church in California.” Seeing himself a “lonely worshipper,” Muir waxed lyrical, “In our best times everything turns into religion, all the world seems a church and the mountains altars.” The seed was sown which grew into the environmental movement we know today.

The Yosemite model of conservation is the original version, and it’s fundamentally anti-people. Its genesis lies largely in the development of beliefs named after sixteenth-century Frenchman Jean Calvin, the second prominent founder of Protestantism in northern Europe.

Calvin was born 26 years after Martin Luther, the German monk who first attacked the appallingly corrupt Catholic clergy. Luther’s theses ended up splitting Western Christianity into its two warring branches. Since then, Protestantism versus traditional Roman Catholicism has become the principal narrative ensnaring much of Western Europe’s history up to the present. Both Lutheranism and Calvinism begat myriad churches and remain among the most important pillars of Protestantism today (though both are still outnumbered globally by Roman Catholics).

To understand why conservation is viewed so differently where Calvinism never gained much sway, involves recognizing the divergence between Jean Calvin’s core beliefs and those of most Roman Catholics. Comparing two complex theologies in a sentence is a fool’s errand but, in a nutshell, Calvinism tends to emphasize the importance of the individual rather more than it does society as a whole.

This distinction becomes clear when comparing the way in which Catholic and Protestant missionaries work across the world today. There are countless exceptions but, broadly, the Catholics seek to establish a congregation and then minister to their flock, whereas the Protestants lean more towards saving individual souls. Non-Christians can be surprised that not only do many in each camp regard the other one as not Christian at all, but that extremist Protestants, even nowadays, see the Roman Catholic Pope as an agent of Satan, the chief devil himself!

Calvinism revolved around three core precepts – the Bible was literal truth, God manifested through the visible creation (“nature”), and humankind was sinful. It placed less emphasis on New Testament teachings about human love or charity, as taught for example through the “good Samaritan” or “love thy neighbor” (which isn’t, of course, to say that Calvinists aren’t loving or charitable).4 Downplaying the view that individuals might attain salvation through compassion and good works, it stressed belief above all things. In Calvinist theology, we can do little – actually, nothing at all – to ensure we’re “saved:” God’s decision about that is immutable and timeless. A few are chosen, the vast majority aren’t.

The first Europeans to settle permanently in North America were Roman Catholics. Later, colonists hailing from the northern European heartlands of Calvinist Protestantism – the British Isles, Germany and the Netherlands – famously began taking their new religion to the American colonies (as well as to southern Africa, which is relevant, as I’ll point out).

It was their theology, eventually syncretizing and borrowing from romanticism’s enrapture with landscape, which directly informed the birth of the conservation movement. Nature was divine and humankind was evil; a few people were righteous (in this case, those who believed in conservation), most weren’t.

Although Catholics were still the largest denomination in the United States when conservation was created in the nineteenth century, prominent environmentalists invariably hailed from Protestant backgrounds. Henry D. Thoreau was a “transcendentalist”, a belief descended from Calvinism. Aldo Leopold, author of the famous “A Sand County Almanac,” was born into a family of Lutheran Protestants (his first language was German) and went to Bible classes at Yale. He believed in, “a mystical supreme power that guided the universe… more akin to the laws of nature.”5 Rachel Carson, author of the equally famous “Silent Spring,” was the daughter of a devout Presbyterian (Presbyterians are Calvinists). She wrote, “the rain and the wind were God’s,” and “the stream of life would flow (along) whatever course that God had appointed.”6 David Brower, a founder of Friends of the Earth and perhaps the most famous twentieth-century environmentalist in California, characterized himself as a “dropout Presbyterian,” and lectured on “drawing people into the religion,” even referring to his talks as “The Sermon.”

These are the “prophets” of conservation, household names among American environmentalists. Many of them might have disavowed the established religion underlying their worldview, and many could not themselves be characterized as anti-people or, least of all, held responsible for conservation’s crimes. Nonetheless it’s clear that Protestantism in general, and Calvinism in particular, shaped both secular ideological systems dominant in today’s United States, environmental protection and economic progress (as Robert H. Nelson convincingly shows).7

Recognizing the divine in nature obviously isn’t confined to Protestantism: It’s widespread, perhaps ubiquitous. Native Americans do it, though in rather different ways, as do Roman Catholics. Belief in nature’s holiness is not the problem with the United States’ approach: What’s wrong is the doctrine that “wilderness” must inevitably mean “without people.” That single idea, pitting sinful humankind at loggerheads with heavenly nature, has disastrous consequences for conservation and it derives directly from its theological origins.

It’s important to grasp how rigidly the American, people-free concept of conservation is enforced. For example, paths in the “wilderness” zones of Yosemite National Park (away from the Disneyland-like Valley itself) are only lightly marked, with dwellings and economic activities forbidden. Backpackers must preregister both their route and the strictly designated places they’re allowed to camp. They pay, and must carry their permit or risk ejection. When the rangers decide a given path has enough trekkers, they simply stop issuing tickets. Visitors are ordered to carry out everything, even used toilet paper!

Fervent advocates of this American “wilderness” worship it as a hallowed sanctuary where people are tolerated only on sufferance, when they agree to the ruling commandments, and pay for the privilege. According to the theology, such “pilgrims” undoubtedly get something big – very big – back for their bucks: As former Presbyterian, John Muir expounded, “In God’s wildness lies the hope of the world,” and he went on, “nothing truly wild is unclean.” By the 1990s, when Roger G. Kennedy, head of the National Park Service, sermonized, “We should conceive of wilderness as part of our religious life,”8 the “wild” had become an article of faith far beyond the bounds of Calvinism.

Nonetheless, the religious connection is never far from the surface. Two of environmentalism’s recent gurus are Dave Foreman and Doug Tomkins. Foreman is a founder of Earth First! and a former director of the Sierra Club. Before his revelation that, “Earth is Goddess and the proper object of human worship,” he had considered becoming a preacher. Tomkins, millionaire co-founder of North Face and the man behind protected zones in Chile and Argentina, was equally to the point, “The concept of sharing the planet with other creatures to me is a religious position… That… is the ethic that informs biodiversity conservation.”9 The famous “father of biodiversity,” E.O. Wilson, was also a devout Protestant in his youth.

Some of these folk go as far as bending language to fit their faith, with the very unlikely story that the English terms “wild” and “self-willed” once meant the same thing.10 “Wild Nature” (often capitalized, like God) is supposedly the same as “self-willed Nature.” Once upon a time, or so the conceit goes, people understood that “wilderness” followed its own, “self-willed” plan which humans were condemned to wreck – just as (or really perhaps, because) Eve corrupted Adam, leading to humankind’s well-deserved eviction from Paradise. Characterizing the world as a battleground between sinful man and divine Nature is, obviously enough, a religious proposition which has nothing to do with science.

What is certain in the minds of those who follow this dogma is that people – apart from themselves – are barely tolerated in Eden’s wilderness. Dave Foreman is far from alone in seeing humanity as “a malignancy” and in thinking that the world population must be reduced to two billion from the current seven. Of course few environmentalists dare openly venture any vision about how seventy per cent of humankind might vanish. One jocular exception is the first U.K. president of the World Wildlife Fund, the Duke of Edinburgh, who reportedly said, “In the event that I am reincarnated, I would like to return as a deadly virus, to contribute something to solving overpopulation.” (A goal which seems to be eluding him as he has, so far, no less than seventeen direct descendants.) Anne Petermann, head of Global Justice Ecology Project, put it even more graphically when she used to join Earth First! chants, “Billions are living that should be dead,” and, “Fuck the human race.”11 (She now campaigns for Indigenous peoples as well as the environment so presumably has changed her mind about part of the human race.)

Many environmentalists are unabashed about their work not serving humankind; if some of their initiatives do end up benefiting people, that’s purely incidental.12 They seek rather to promulgate Nature for its own sake, believing they are beholden to its “will” alone, and certainly not to man’s. Replace the word “nature” in their musings with “God” and their theological heritage is unambiguous.

They are not bothered if no one – apart from them – visits the protected zones they claim to speak on behalf of, the fewer the better in fact. Some have taken their views to the wildest extremes. Jonathan Spiro13 shows how American conservationists were in the forefront of both the eugenics movement and the opposition to immigration from “non-Aryan” countries (or looked at another way, largely from Catholics and Jews) in the early twentieth century. He also describes how their misanthropic agenda opposed “mixed-race” marriages and supported compulsory sterilization.14

This wasn’t just coincidence, as some present-day environmentalists are keen to claim. They like to believe that such views were universal, but they weren’t: There were always voices arguing for racial equality and compassion.15 However uncomfortable it may be to admit it nowadays, the truth is that there was a direct link between eugenics and conservation’s invention of game management – culling the weak to keep the species strong.16

Indeed, blaming overpopulation for environmental degradation remains commonplace today.17 It’s obviously not without foundation, but in reality the U.S.A. is still sparsely populated. For it to approach the same density as Great Britain, for example, would involve an eightfold increase in the number of its inhabitants. (It is also worth pointing out that America’s population could still grow by nearly that much and yet burn up no more resources than it does now – if, that is, everyone consumed no more than the average human being does in Mexico or Central America.)

Despite the lack of any real threat to the environment from “immigration,” it was still widely seen as endangering the U.S. landscape, with the Sierra Club – itself set up by a Scottish immigrant, John Muir – openly opposing it for decades before finally dropping the matter at the end of the 1990s.18 That decision provoked Earth First! founder, Dave Foreman, to quit the club’s board, and many leading environmentalists – despite being descended from immigrants themselves – still see immigration and population as the world’s biggest problem. Foreman routinely blames the Catholic Church, but feminism is also in his cross hairs, for “taking over” family planning “to let women do whatever they wanted to.”19

The real pressure on the environment, and not just nationally, comes from America’s high levels of consumption, rather than from simple population density, but the former is far too sacred a cow for most professional environmentalists to confront. It’s also true that those generously paid folk setting the agenda in the big conservation organizations, jetting from conference to consultation and back, usually have a “carbon footprint” very much bigger than most of us.

The United States is the principal driver and paymaster of environmentalism but Europe is a close second, and things there could not be more different. For Europeans familiar with their national parks, where hikers can pretty much come and go and bivouac overnight as they please,20 American restrictions might be surprising. Europeans can revere nature as much as anyone, but people’s integration into the landscape is also embraced. It’s a very big difference.

European national parks frequently encompass working farms, villages, and even whole towns. How humankind has marked its surroundings is celebrated. For example, most European mountains lie within protected areas but they are still strewn with shrines, and crowned with huge Christian crosses, visible from a distance and dwarfing those souls who attain their summits. These are often inscribed with an inspirational verse, usually invoking divinity.21

In a continent where written history covers thousands of years, where ancient peoples built massive stone buildings and roads, and which is known to have been inhabited by Homo sapiens for over forty thousand years, and by Neanderthals for ten times longer, any notion of “wilderness untrammelled by man” – to quote the problematic phrase from the 1964 United States Wilderness Act – sounds like the blind and blinding mistake it actually is.

Europe’s protected areas do still show their wild side, but I can find no conservation zone on that continent which has been founded on the eviction or killing of its inhabitants. This isn’t because of different interpretations of religion or “wilderness,” it’s because the resultant outcry would immediately kill off popular support for conservation (which in Europe is still largely funded from the Protestant heartlands of Britain and Germany).

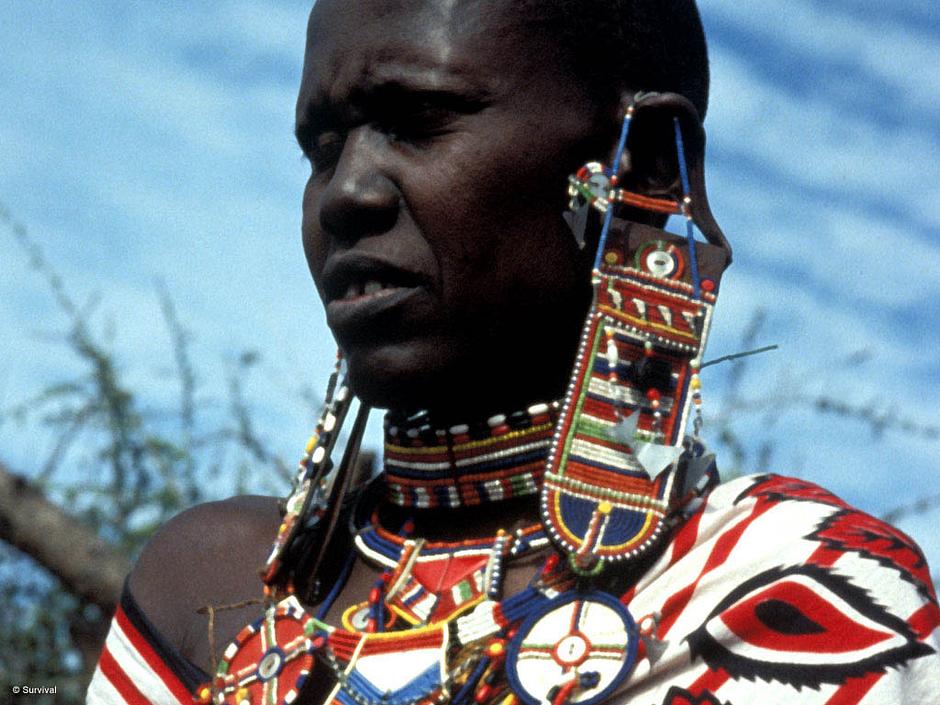

Tragically for tribal peoples however, it was the earlier, American, model which was exported to Africa and Asia. This saw practically every African protected area, as well as many in Asia, stolen from tribal and other local people. The theft is ongoing and has entailed the forced evictions of millions.22 Entire tribes have been destroyed in the process, just as they were in the nineteenth-century United States. Shamefully, there was and is no loud, popular outcry in opposition to this.

Although the model was American, the crime can be laid at the door of north Europeans: With the (apparent) exception of Virunga, Africa’s first park,23 the empires behind the imposition of the major national parks in Africa were largely British, French and German, while those who created the South African conservation zones were descended from Dutch and French Huguenot colonists. It’s easy to see African parks, and the entire “African wilderness” fantasy for that matter, as the invention of people with the same ethnic and religious – almost always Protestant – heritage as conservation’s founding fathers from the United States.

The creed of empty wilderness is a racist construct. Africa is where our species started perhaps two hundred thousand years ago and we’ve occupied North America for at least fifteen thousand years if not much longer. There is now a growing body of scientific evidence proving that tribal peoples altered their lands everywhere over thousands of years, planting, clearing, burning, encouraging herd grazing, and using all manner of other ways that conservationists couldn’t see, to manage the animals and plants that gave them life. Like everyone, they were actively adapting the ecosystem to improve their living.

However, nineteenth-century racism meant that these environmental impacts went unrecognized when the American national park model was invented. The truth is, none of these areas were “empty” in the first place, but their black- and brown-skinned inhabitants were not considered as human as hubristic white conservationists. They were supposedly lower on the evolutionary scale, or even below it entirely.

It was precisely because they were “barely human” that their lands could be called uninhabited and pristine, and their territories then made uninhabited by chucking them out. Tragically, just as the colonists’ narrow vision prevented them seeing the way Indigenous peoples had managed their lands, many environmentalists today still don’t.

Most Western “ecotourists” don’t know that the national parks they pay to visit in Africa and parts of Asia were forcibly emptied in order to create an artificial “wilderness.” Supporters of environmental causes are among the most public-spirited and humane folk, and many would be shocked to realize that illegal evictions and human rights abuses are still widespread in the name of conservation, and that anti-poaching schemes rely increasingly on extra-judicial – in other words, illegal – killing, mostly of poor locals.

Though many experts know it only too well, none of the big conservation organizations publicly acknowledges that the lethal “green” militarization they’ve unleashed is worse than useless at tackling the real enablers of poaching, corrupt officials. Ordinary environmental supporters don’t realize that these include members of the same government departments that are financed directly through their donations.24 It’s madness, and is bound to make things worse. There is an enormous amount of dissimulation at work in the supposed safeguarding of nature and the public is routinely being conned.

It’s certain that if they continue to alienate local people, conservationists themselves will soon be tolling conservation’s death knell. We’re constantly told poaching is on the increase, for example, but we’re never told that’s largely because of their deeply flawed strategies. If we want to protect the environment, as we surely do, we have to wake up to the fact that the term “wilderness” has been hijacked for the homelands of peoples who were booted out to fulfill the biblical tale of an empty Eden.

It’s time to banish this antediluvian homily from the environmentalist canon. It’s time to start approaching the tribal peoples and other local inhabitants who live in and near conservation zones with the respect they deserve. In most cases it’s they who created the so-called “wilderness” in the first place, and so if we see it as divinely inspiring we must welcome them as its foremost practical guardians and support them in this role.

That will involve facing squarely up to the crimes caused by conservation. Environmentalism’s success will largely depend on whether the leaders of the conservation movement and the billion-dollar industry under them care more about protecting their myth of an untouched Eden than they do about the real “natural” world, which people have nurtured and shaped over millennia.

The 1850s was a shape-shifting epoch. Whites destroyed the Yosemite Indians then ordained their land hallowed, so scripting conservation’s romantic creation myth. Darwin put paid to the ancient biblical version of creation with his bestseller, “On the Origin of Species,” at the same time ushering in a satanic new myth – today called “scientific” racism.25 In the same decade, Henry D. Thoreau gave us his crazy masterpiece of American literature in which he sensibly counselled, “It is never too late to give up our prejudices.”26 He was surely right. History is more than self-serving entertainment, it is a guide and mentor which can lead us away from endlessly repeating past cruelties, and at least point us in the direction of something better for everyone.

The empty wilderness isn’t Paradise on Earth, it’s a false idol which desecrates the graves and memories of its creators and is still killing people today. Understanding this won’t diminish environmentalism or damage nature at all: On the contrary, it’ll galvanize its real and lasting security. Our divine planet, where a form of scripture is indeed “written on every cliff,” is surely worth protecting properly, including from the deliriums of the conservation industry: After all, it’s our only real heritage.

Stephen Corry is thankful for the chance to walk and climb in national parks on several continents over half a century – and finds them divinely inspiring. He has worked with Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights, since 1972. The not-for-profit, which is successful at halting the eviction of tribal peoples from their ancestral homelands, has an office in the San Francisco Bay area. Its public campaign to change conservation can be joined at https://www.survivalinternational.org/conservation. This is one of a series27 of articles on the problem.

___________

Footnotes

1 Ralph Simpson Kuykendall, Early History of Yosemite Valley (Washington: Washington Government Printing Office, 1919), https://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/early_history_of_yosemite_valley/.

2 Overall the Californian genocide eradicated about 90% of Indians in the span of a couple of generations. See Benjamin Madley, “It’s time to acknowledge the genocide of California’s Indians,” Los Angeles Times, May 22, 2016, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-madley-california-genocide-20160522-snap-story.html.

3 Kuykendall, Early History of Yosemite Valley.

4 Martin Luther’s original 1517 “Theses” did suggest giving to the needy was better than paying the clergy; and the teaching that individuals should behave as if they were one of God’s chosen is widespread in Protestantism.

5 Curt Meine, Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1988) 506-7, https://www.religionandnature.com/ern/sample/Meine—Leopold.pdf.

6 Yaakov Garb, “The Politics of Nature in Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring,” in Minding Nature: The Philosophers of Ecology, ed. Dave Macauley (New York: The Guilford Press, 1996) 250, https://goo.gl/r2oMCt.

7 Robert H Nelson, The New Holy Wars: Economic Religion Versus Environmental Religion in Contemporary America (Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 2010).

8 Ibid., 65.

9 Doug Tompkins, interview by Paul Kingsnorth, Chile, 2011, transcript in The Dark Mountain Project, December 16, 2015, https://dark-mountain.net/blog/doug-tompkins-remembered/.

10 No one is certain about the etymological origin of “wild” in Germanic languages.

11 Nelson, The New Holy Wars, 121.

12 Frances L. Flannery, Understanding Apocalyptic Terrorism: Countering the Radical Mindset (Oxon: Routledge, 2016), https://goo.gl/rY9tvQ.

13 Jonathan Peter Spiro, Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant (Vermont: University of Vermont Press, 2009).

14 Laws against “miscegenation” weren’t fully abolished until 1967 in the United States, and compulsory sterilization was still happening in 1981, and possibly much later.

15 Perhaps most famously, the German-American anthropologist Franz Boas (1858-1942) in the United States and the writer G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936) in Britain. Interestingly, the former was of Jewish descent and the latter a convert to Roman Catholicism.

16 Stephen Corry, “Whose environment, whose law? or Why Darwin is dangerously wrong” (presentation – Keynote speaker 3, Public Interest Environmental Law Conference, University of Oregon, OR, February 28, 2014), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7RcN8PTKdNg (from 27 mins).

17 American environmentalism has been involved in the debate over immigration since its earliest days. A hundred years ago many leading conservationists opposed immigration from southern and eastern Europe, principally for reasons of eugenics: They didn’t want “non-Aryans” such as Italians, Greeks and Jews, to “swamp” the “Nordic race” which had colonized the United States. More recently the opposition has been focussed against “Latinos” from Mexico and Central and South America.

18 Brentin Mock, “How the Sierra Club Learned to Love Immigration,” Color Lines, May 8, 2013, https://www.colorlines.com/articles/how-sierra-club-learned-love-immigration.

19 Dave Foreman, “Rewilding North America” (presentation during his book-selling tour, Southern University of Oregon, OR, October 23, 2013), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w92mpvcWoW4.

20 Technically, much land in English and Welsh national parks, for example, is privately owned and the landowner’s permission should be sought before spending the night. In reality, few bother. I am not alone in having spent countless nights, unchallenged, in “wild” places inside protected zones in several European countries.

21 A favourite of mine is from Austria and is a deliberate misquote from the 12th century German saint, Hildegard von Bingen, “Where love abounds, there are the mountains, for that is God’s realm.”

22 Estimates vary from five million to several tens of millions. Charles Geisler puts the number in Africa to at least fourteen million. https://orionmagazine.org/article/conservation-refugees/.

23 Virunga was created in the Belgian Congo in 1925 and initially named after Belgium’s Roman Catholic King Albert. However, the park’s prime mover was really Carl Akeley, big-game hunter and “father of taxidermy” from the American Museum of Natural History.

24 Stephen Corry, “Wildlife Conservation Efforts Are Violating Tribal Peoples’ Rights,” Truthout, February 3, 2015, https://www.truth-out.org/op-ed/item/28888-wildlife-conservation-efforts-are-violating-tribal-peoples-rights, and Corry, “When Conservationists Militarize, Who’s The Real Poacher?” Truthout, August 9, 2015, https://www.truth-out.org/op-ed/item/32255-when-conservationists-militarize-who-s-the-real-poacher.

25 Darwin first denigrated the Indians of Tierra del Fuego in his journals in 1832 and summarized his ideas forty years later in “The Descent of Man.” The work which was first widely noticed, however, was the 1859 “On the Origin of Species”. The full-blown idea of eugenics was devised by Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton, in 1883 and had been widely taken up by the end of the nineteenth century. It still underpins racism today. See also Corry, “When Conservationists Militarize.”

26 Henry D Thoreau, Walden (New Jersey: Princeton, 1971), 8.

27 See https://www.truth-out.org/author/itemlist/user/47328.