Resettlement ravages the Canadian Innu

Innu man George Rich talks to Survival International about the decline of his peoples’ health and culture following a programme of forced resettlement.

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

How long have the Innu people lived in north east Canada?

Innu have lived in this land we call ntessinan for thousands of years, traveling back and forth to the interior and reaching the coastal shoreline in the summer.

My grandfather comes from the interior of Ntessinan (‘our land’), and lived most of his life in Nutshimits (‘the country’). When the traders and missionaries started to come in the coast, our people settled in a small village for trapping, and to trade goods to the traders.

Innu always follow the caribou migration, mainly because caribou is the main source of the Innu diet. We know where the caribou calving grounds are, and where caribou winter.

Almost every place in this land has an Innu name.

The Innu are a hunting people. How have they survived in harsh lands?

Innu have tremendous knowledge of the conditions of the land, climate, features of the landscape and where the animals are.

We have passed on to our children the knowledge of survival, which is essential for them because they must constantly depend on themselves.

Can you give examples of specific clues you look out for in the country?

Open water in a lake usually means that geese and ducks will be around in the springtime. Many sea gulls in open water mean there are fish in the area, and broken branches in the trees show that a bear den is nearby.

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

Can you describe the lands where your family is from?

I am currently living in Natuashish, on the coast of Labrador. The area is surround by boreal forest and mountain terrain; further into the interior, you find tundra – these are barren lands, where our people hunt for caribou.

I grew up in the country before the age of 15. I always lived in a tent until the new community of Davis Inlet was constructed in 1969. The Canadian government wanted to settle our people in order to educate our children like whitemen.

My parents tried to maintain our way life until we got our house in the late 1970s. Then, we were forced to go to school. I remember once when my late father took us out of school to go to the Innu fall camp. The teacher followed us home and took us back to school.

How important are your ancestral lands to the Innu on a spiritual level?

As a lot of elders have said to us, the land is a part of your life.

Without it, you are nothing; the animals, the plants, and everything that is connected to the land are symbols of Innu identity – of who you are as a human being.

What is the significance of caribou to the Innu people?

The caribou is the main source of life for the Innu; we depend on the meat as a food source, and on their hides for clothing and shelter for our tents.

Our legends and stories of the caribou show our respect and gratitude to this animal. Even today, in the 21st century, we honor it by showing it in our community logo and flag.

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

Can you tell us about the Innu people’s traditional knowledge of the natural environment? Which plants you use for medicinal purposes, for example?

There are plants and animal parts that are used for medicinal purposes when people are ill; mostly for coughs, flu, and muscle aches.

The Innu women always gather berries in the late summer and early spring and store them to use over the winter. The gall bladder of the bear is used for many things, such as to stop an infection; it is applied to wounds or cuts. Seal fat is used for colds and flu; the fat is melted into oil, and people who are ill drink it. The blackish vegetative growth around the huge rocks is pounded into a powder and boiled to drink.

My mother mentioned to me once that my late brother used to have a lot of warts on his hands. She took him to the elder and the elder told my mother to kill a mouse and bring it to him. The elder took the blood of the mouse and sprayed it on my brother’s warts. A few days later all his warts disappeared.

What changes can you see in the country today that may be caused by climate change?

In the last few years, we have noticed a sudden change in weather. It now rains in the winter months; and in early spring and late winter we can have extremely cold weather for days. This sometimes causes problems with the wildlife.

For example, a black bear emerged from his den in the middle of winter after it had been raining for a few days. The black bear was starving because there was no food for it at that time of year.

© Serge Jauvin/Survival

© Serge Jauvin/Survival

What skills do you teach your children today?

Today, adults in the community take the youth out in the country to teach them traditional skills integral to our way of life, such as hunting and canoeing, and how to take care of the animals they kill.

For example, you have to butcher a caribou in a certain way. If you cut it in a disrespectful way, you will offend the animal spirit. You also have to be very careful where you place the caribou bones and the caribou head, because the animal spirit needs to be respected. And the bone marrow of the caribou bone should be treated with the upmost respect.

A community gathering takes place once a year in the spring, which is all about teaching the Innu youth how to survive on the land.

Do you speak Innu-aimun?

My first language is Innu-aimun, I speak it 99% of the time at home. Speaking your language every day provides your identity. It is part of your heritage and of being and Innu person.

How do the Innu people perceive the relationship between man and nature?

It is mostly respect. As a young man, I was taught to respect nature, such as snow, water, fire and animals. I was told to respect these elements just as I respect other human beings.

What happened in the 1960s? How did the government persuade the Innu to live in resettlement communities?

This was another plot of the government to assimilate the Innu people and to take them away from their homelands, to control them and make them something other than they are.

They sent the missionaries to beat the ‘devil’ out of us and turn us into Christians, but that didn’t work.

When they succeeded in getting the Innu people out of their traditional lands, they flooded our lands and cut the trees in the forest.

We ended up in a corral, begging for handouts from the government.

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

How did this affect the Innu self-esteem and identity?

If you are taught that your way of life is no good, what can you do? And when you are forced to live this new way of life, what are the chances you’ve got? Unemployed and uneducated in the whiteman’s world – not only can you not compete in the whiteman’s world, you have also lost the connection to your own way of life; so now you are uneducated in both worlds – Innu and non-Innu.

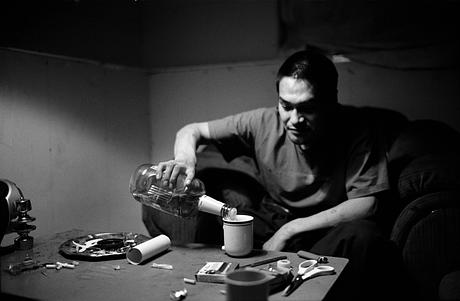

The only solution to hide the pain is turn to the bottle of destruction.

What were the results, and the ongoing problems, of assimilation?

We used to have viable and strong communities, but we are now discontent to live the traditional way of life. We created communities that don’t feel like communities at all. Everyone has their own agendas.

Some have thoughts of Innu communities living more in the whiteman’s world in the future, where money flows like a river in the pockets of the Innu people.

The Innu way of life will be a struggle to keep. Programs are in place to live the Innu way of life, but the social problems in the communities are really very serious.

Why do you think Innu communities have, tragically, some of the highest suicide rates in the world?

Thinking back on it now, I believe some white teachers and priests sexually abused the children when they taught at our school.

We found the Christian religion and schooling was confusing compared to what we were taught at home, and that led us to believe that we are worthless and have nothing to continue to live for.

The continuing assimilation of the Innu has a huge impact among our youth. Many of them have no self-respect.

We live a life that doesn’t exist. We are caught between two worlds; one that has lost its connection to the land and animals.

© Adam Hinton/Survival

© Adam Hinton/Survival

© Adam Hinton/Survival

Many false beliefs still exist about tribal peoples. What is your message for people about out-dated beliefs about tribal peoples?

It is hard to eradicate things that are damaging to tribal peoples.

Education is the answer. In every society, there exists a lack of understanding of other peoples’ cultural and religious beliefs, but one has to experience other cultures and see them on the same level as all societies.

In Innu culture, everyone from a child to elder is listened to and heard, because we believe we all have something to offer.

If you had one message for other tribal peoples of the world – from Africa to the Amazon and the Arctic – who are facing similar problems, what would it be?

Let us keep up the awareness and continue to inform the public about what is happening to the tribal peoples of the world.

The loss of ways of life and languages is the first sign of extinction of ones culture. We need to maintain tribal ways of life for the survival of all human beings.

There are a lot of caring people left. They can help to change the world.