Parks and Peoples

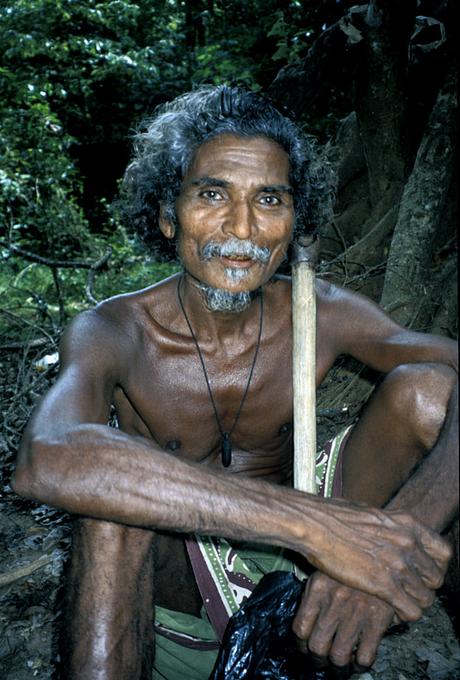

The original conservationists

80% of the world’s biologically richest places are the territories of tribal communities who have lived there for millennia. This is no coincidence. Tribal peoples have protected the diversity of species around them by developing ways to live well on the land they cherish.

The creation of conservation areas has led to hundreds of thousands of tribal peoples being evicted. They are among the world’s millions of ‘conservation refugees.’

But it does not have to be this way.

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

Many tribes see themselves as stewards of their children’s and grandchildren’s land, an approach that is naturally allied to conservation. Indigenous territories cover five-times as much of the Amazon basin as protected areas and are the most important barrier to deforestation there.

Scientific studies based on satellite data have shown that Indigenous territories are highly effective and vitally important for stopping deforestation and forest fires

Guns and guards

The world’s 100,000 parks, or protected areas, cover 13% of the land surface of the Earth and have created an estimated 130 million conservation refugees who have lost their homes and livelihoods to parks.

Many tribal peoples first learn that their land has become a park when conservation officers turn up to tell them to stop hunting, stop cultivating or to leave altogether.

Park guards – and their guns – wield great power over the local people, criminalising their behaviour.

The first national park – a model for the future?

Yellowstone National Park in the United States was the world’s first national park.

Its creation cost the lives of many of the Shoshone, Blackfoot and Crow peoples who lived there, yet this model of forced eviction for conservation has been exported worldwide, with devastating impacts.

One example is Bwindi Impenetrable Forest in Uganda where the lives of many Batwa ‘Pygmies’ have been devastated since they were barred from the area that was once home.

Ngorongoro

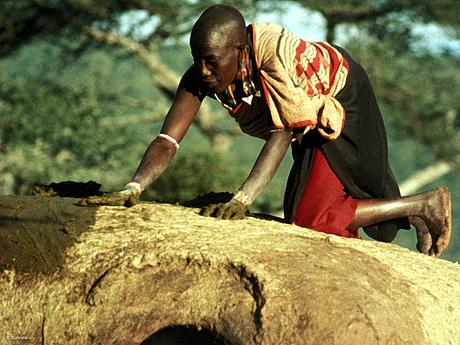

The dramatic landscape of Ngorongoro in Tanzania is one of the world’s most famous conservation areas.

Few visitors realise, however, that in the 1970s, evictions from one half – the Serengeti National Park – crowded the resident Maasai and their animals into the Ngorongoro Conservation Area.

© Adrian Arbib/Survival

© Adrian Arbib/Survival

hut. Once hard, it provides a waterproof shell and a rigid structure.

Then the Maasai were stopped from grazing their animals in the famous Ngorongoro Crater, the rich grasses and water sources of which were vital resources for the Maasai of the wider area.

The Maasai were given no warning. Paramilitary personnel simply arrived one morning and evicted the families from the Crater, dumping their belongings on a roadside.

The famous crater has now become severely degraded. UNESCO has threatened to remove its World Heritage status. In early 2010, the government responded by calling for the removal of the thousands of Maasai who use the crater. Their fate is undecided.

Sign up to the mailing list

Our amazing network of supporters and activists have played a pivotal role in everything we’ve achieved over the past 50 years. Sign up now for updates and actions.