Q&A with Davi Kopenawa

h4. In April 2014 Davi Kopenawa, a shaman and spokesman of the Yanomami tribe, visited the San Francisco Bay Area to talk about the urgent need to safeguard the world’s rainforests for future generations.

h4. Tens of thousands of people tuned in to Davi’s live ‘Ask Me Anything’ session on the website Reddit, where he answered questions from members of the public about shamanism, rainforest life, racism and the portrayal of the Yanomami people as ‘violent’ by anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon and others.

The full Q&A is available on Reddit. Read excerpts below. Davi Kopenawa: Olá Reddit! My name is Davi Kopenawa. I live in the Amazon rainforest of Brazil, in a village called Watoriki, or ‘the windy mountain.’ I am a shaman and spokesperson for the Yanomami, the largest relatively isolated tribe in South America.

I’m in San Francisco, California with the organization Survival International for a series of talks about the campaign to demarcate Yanomami territory and the importance of preserving the Amazon for all of humanity. Fiona Watson, Survival’s research director, will be translating my answers from Portuguese.

Watoriki is a very big, tall mountain. We call this mountain Watoriki because it means 'the windy mountain'. The wind is always blowing around the community, so that we breathe well - it's very clean air. We've lived there for many years. We don't want to ever leave there. We always want our round house - yano, a symbol of the earth because it's round - we always want to have our Yano there. h4. What sorts of skills did you learn as a shaman?

I asked the oldest shaman to teach me to become a shaman. So he prepared what we call 'yakoana', and he told me that it's not easy to be a shaman. He said you must not eat, you must not take a bath, you cannot eat meat, no fish, you have to remain in silence, and you have to feel hunger. The great shamans don't allow you to eat - you have to clean out all your body because in our stomachs we have rot. So you have to be in this state for weeks. You have to prepare yourself - you have to look at all the other shamans. And then all the shamans and the shamanic spirits arrive near you. And the shamanic spirits live in a very big house - a shabono - and they bring that with them to the shaman. Each spirit of the forest has a name, there are lots of different spirits - they all arrive, and then the oldest shaman will show the spirits how to work. The work of the spirits is to cure, to heal people. So they will take the illness. The shamans get them to hit the disease and get rid of the disease. So 'xawara', the bad spirit, falls onto the ground. Then the shaman takes it and throws it very far away. Then the shaman cleans out the body with special water that he has - then the person is cured. h4. Are the xapiri _[shamanic spirits]_ aware that there is a battle going on between those who are aware of plant spirit and those who are not? The people who are not aware of plant spirit take no care of the planet. Do the xapiri know of a way to help people wake up and realize the destruction of our planet is real? We cannot do this without their help.

Yes. The xapiri are in contact with lots of different places. They receive messages and news that come from very far away. A shaman in a village will be receiving this news from very far away. They will know that there is a lot of rain, or that it's becoming very hot in places where there is no rain, that the rivers are getting angry, and that there will be a lot of storms. The shamans in the community are receiving this news via the shamanic spirits from all around the world. h4. Do you find that there is a lot of prejudice or racism against indigenous people?

Yes. Prejudice is everywhere. We find it in the city, in villages, in small communities. In fact, everywhere in the world, you find prejudice. h4. What is your favorite rainforest animal?

My favorite animals are the macaw, the parrot, and the eagle. h4. What was your first experience of the developed world like?

I left my community, Tototoobi, for the first time. I went together with an employee of FUNAI (the Brazilian indigenous affairs organization) and I arrived in the municipality of Barcelos. The first time I saw that place of electric light and the houses all together, crammed like matchboxes, and lots of people walking in the street, I felt a lot of curiosity and I wanted to get to know them. I thought, "Who are these people? Where did they come from? How did they get here?" That's what I thought on my first visit to the city. h4. Did you have any negative feelings about cities like that? I.e., disbelief or pity that people lived like that? Or were you just intrigued by another way of life?

I think city life is very complicated. It's difficult to live in the city for me as an indigenous person. I think the rest is good, it's nice, but it's nice for the white people. It's your home. I can only stay about 5 or 6 days in the city, and then I have to go back to my shabono. h4. After seeing the developed world, would you rather stay in San Francisco than go back to your village?

I prefer to return to where I am from. That's my place - it's where I was born and that's the best place for me. Here in the city it's the land of the white people. h4. Are there any luxuries or technology from the city that you will really miss?

There is technology that would be useful for the Yanomami. Technology that is not contaminated is good. For examples, solar panels, which act like a battery receiving energy from the sun. That's good for the communities, that helps us look after our health. Microscopes are good, and so are things like toothpaste. Things that you use to examine your heart are good. Also communications equipment, like two-way radios. Today our children are learning to use computers to send news to the city from the community. They also write up documents on the computer. For us indigenous peoples, those types of technology are important. h4. I am an anthropology grad student and a supporter of Survival International. I have certainly read a wealth of literature regarding the Yanomami in my studies and am very excited for this AMA. I have always wondered about Survival International (and others like it as well as anthropologists in the field) and its true impact on the lives of those it seeks to assist. Do many of the communities (yours included of course) feel that they are doing adequate work? If not what do these communities feel the organization (or its members as individuals) could improve upon in order to help educate other populations around the world.

The work of Survival is good work. They work very well defending indigenous peoples, and they also protect the places where Indians live. They spread the word, they're always giving lots of news. That's the role of Survival, and it's very good. Survival International was born because of the indigenous peoples. It's their cause. It's unique. The non-Indian people who support indigenous peoples, they can support indigenous organizations in their projects. h4. Pajé Kopenawa, good afternoon. I worked for an official organ of Human Rights along the Governo da Bahia, in Salvador a long time ago, and I must say that all of us Brazilians could have some more respect about the indigenous people, not only in the Amazon, but in the whole country. I don't think the government or the media let the people to be really aware of what's really going on around the indigenous territories. In your opinion, what could be changed for FUNAI to work better for you and what could be changed in the Brazilian media to help the rest of the people to understand better your people's affair?

First the government itself has to change. That's starting from the top of the government. Change the head of state, and then FUNAI can change to make its work better for indigenous people. It's the federal government that supports FUNAI, and it has to value FUNAI's work and give it money, especially for the indigenous territories that are not demarcated and to protect territories, which are already demarcated. FUNAI has to also protect the borders of indigenous territories to stop the invaders coming in. That is what is needed from FUNAI.

I think the media don't like to talk about the problems in Brazil. In fact, they like to hide them, so that other countries don't know about them. It would be really good if the TV, radio and internet could send out the real news so that we could communicate. h4. Can you describe the hardships that your tribe and other isolated tribes have experienced in the Amazon at the hands of prospectors, poachers and loggers? With the frontier continuing to consume the Amazon, do you think the truly isolated and uncontacted tribes, such as the Arrow People in the Vale do Javari, will survive long term into the future?

We indigenous peoples, we never forget our worries because the destruction is increasing - the search for gold and other minerals, the destruction of the forest for logging, and the non-indigenous population is getting bigger. We're worried about this. So where the indigenous peoples live, like the Yanomami, in fact it's not a lot of land, it's small. The ranchers are coming there, the gold miners, rural workers, mining companies, and many other people who don't have land. Although our territory has been demarcated, it's not guaranteed. So I'm very worried about our future.

I'm also very worried about our brothers and sisters who have not been contacted. In the Yanomami area there are uncontacted people called the Yawari. And on the upper Solimoes River there are other peoples who have not been contacted. They all speak different languages and are different peoples, but nevertheless they are going to suffer a lot - that's my worry. There aren't any non-Indians to defend them. FUNAI defends them, but FUNAI has no money. They don't have plans, they don't have trustworthy people, and they don't have the support of the government to give them the money in order to defend the uncontacted people. So in the future they're going to suffer a lot. h4. Thoughts on Napoleon Chagnon?

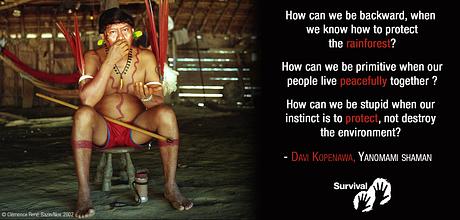

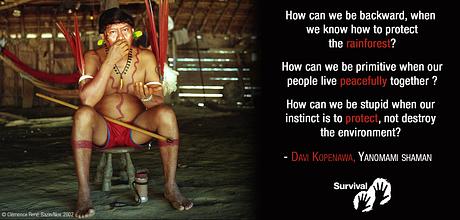

Napoleon Chagnon went to the Yanomami land to learn with us, and to know about our wisdom. Then he learned to speak our Yanomami language, and he changed his ideas, and he decided to play a trick on us. He asked communities to fight amongst themselves, he incentivized fighting, so that those who won in the fights would gain merchandise - pans, knives, etc. That's how Napoleon Chagnon worked. Then he sat down with his pen in his hand, saying that the Yanomami are violent. That is absolutely not the case. What is more violent is the United States, which has killed thousands of people - children, women - and destroyed cities, throwing atomic bombs. He has a lot of prejudice, Chagnon. He is prejudiced against my Yanomami people. Who is the most violent? Him. His people. Chagnon just said the Yanomami are violent without explaining anything. Some Yanomami, like other people, get angry. Every people on earth have their own fights. Men get jealous about women. Women get jealous about their husbands. Some women even beat their husbands. ALL human beings have this within them. h4. Hi Davi, there are some questions here about the 'developed world', but what do you think of the kind of development that is happening in the Amazon?

I think the development being done by the white people is done in the way of the non-Indians. They like building highways and hydroelectric dams for energy. They want to industrialize everything. They want to build great highways to transport things - all the minerals, wood - to other countries. The non-Indians like to do this. This is very bad for the indigenous people. In a sense, some of it is good - it brings in medicine and equipment for health and health teams who work with our communities. And airstrips help the health teams come in to help us. On the other hand it's not good. There are two paths, and the path of health is more important, but the other road is a huge road: the road of illness. It will bring lots of problems. The roads bring in alcoholic drinks, and bad things from the city. h4. How do you stop yourself from getting depressed about the future (of the Amazon, of the world…)?

When I'm in the city, I get very sad because I meet a lot of people who talk about the destruction of the Amazon. I feel even sadder when I hear about large-scale mining happening all around the world in indigenous territories. Those two things make me very sad. We don't know how to resolve this because the authorities are all united together to destroy nature. There are very few people who are defending and fighting together with indigenous peoples. So on the one hand I feel sad, but on the other hand I feel firm knowing that there are other people who will fight, who will protect our forest, who will protect indigenous peoples. I also trust very much in the forces of nature and the work of the shamans. I know that those who are destroying will suffer like we are suffering afterwards. Nature gives me courage so that I'm not sad all the time. © Pablo Levinas/Survival

© Pablo Levinas/Survival

I'm telling you this, so that you'll be happy knowing this. But I need help from the people of the United States. Keep watching, and if you want, support the indigenous organizations in our projects, and this will help conserve the Amazon rainforest. That's my message to you all. Obrigado.

h4. Tens of thousands of people tuned in to Davi’s live ‘Ask Me Anything’ session on the website Reddit, where he answered questions from members of the public about shamanism, rainforest life, racism and the portrayal of the Yanomami people as ‘violent’ by anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon and others.

The full Q&A is available on Reddit. Read excerpts below. Davi Kopenawa: Olá Reddit! My name is Davi Kopenawa. I live in the Amazon rainforest of Brazil, in a village called Watoriki, or ‘the windy mountain.’ I am a shaman and spokesperson for the Yanomami, the largest relatively isolated tribe in South America.

I’m in San Francisco, California with the organization Survival International for a series of talks about the campaign to demarcate Yanomami territory and the importance of preserving the Amazon for all of humanity. Fiona Watson, Survival’s research director, will be translating my answers from Portuguese.

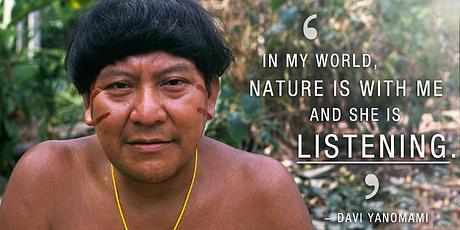

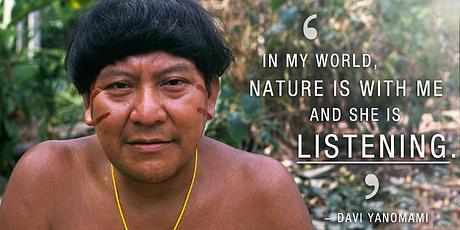

‘In my world, nature is with me and she is listening’. The words of shaman and leading Yanomami spokesman Davi Kopenawa

Watoriki is a very big, tall mountain. We call this mountain Watoriki because it means 'the windy mountain'. The wind is always blowing around the community, so that we breathe well - it's very clean air. We've lived there for many years. We don't want to ever leave there. We always want our round house - yano, a symbol of the earth because it's round - we always want to have our Yano there. h4. What sorts of skills did you learn as a shaman?

I asked the oldest shaman to teach me to become a shaman. So he prepared what we call 'yakoana', and he told me that it's not easy to be a shaman. He said you must not eat, you must not take a bath, you cannot eat meat, no fish, you have to remain in silence, and you have to feel hunger. The great shamans don't allow you to eat - you have to clean out all your body because in our stomachs we have rot. So you have to be in this state for weeks. You have to prepare yourself - you have to look at all the other shamans. And then all the shamans and the shamanic spirits arrive near you. And the shamanic spirits live in a very big house - a shabono - and they bring that with them to the shaman. Each spirit of the forest has a name, there are lots of different spirits - they all arrive, and then the oldest shaman will show the spirits how to work. The work of the spirits is to cure, to heal people. So they will take the illness. The shamans get them to hit the disease and get rid of the disease. So 'xawara', the bad spirit, falls onto the ground. Then the shaman takes it and throws it very far away. Then the shaman cleans out the body with special water that he has - then the person is cured. h4. Are the xapiri _[shamanic spirits]_ aware that there is a battle going on between those who are aware of plant spirit and those who are not? The people who are not aware of plant spirit take no care of the planet. Do the xapiri know of a way to help people wake up and realize the destruction of our planet is real? We cannot do this without their help.

Yes. The xapiri are in contact with lots of different places. They receive messages and news that come from very far away. A shaman in a village will be receiving this news from very far away. They will know that there is a lot of rain, or that it's becoming very hot in places where there is no rain, that the rivers are getting angry, and that there will be a lot of storms. The shamans in the community are receiving this news via the shamanic spirits from all around the world. h4. Do you find that there is a lot of prejudice or racism against indigenous people?

Yes. Prejudice is everywhere. We find it in the city, in villages, in small communities. In fact, everywhere in the world, you find prejudice. h4. What is your favorite rainforest animal?

My favorite animals are the macaw, the parrot, and the eagle. h4. What was your first experience of the developed world like?

I left my community, Tototoobi, for the first time. I went together with an employee of FUNAI (the Brazilian indigenous affairs organization) and I arrived in the municipality of Barcelos. The first time I saw that place of electric light and the houses all together, crammed like matchboxes, and lots of people walking in the street, I felt a lot of curiosity and I wanted to get to know them. I thought, "Who are these people? Where did they come from? How did they get here?" That's what I thought on my first visit to the city. h4. Did you have any negative feelings about cities like that? I.e., disbelief or pity that people lived like that? Or were you just intrigued by another way of life?

I think city life is very complicated. It's difficult to live in the city for me as an indigenous person. I think the rest is good, it's nice, but it's nice for the white people. It's your home. I can only stay about 5 or 6 days in the city, and then I have to go back to my shabono. h4. After seeing the developed world, would you rather stay in San Francisco than go back to your village?

I prefer to return to where I am from. That's my place - it's where I was born and that's the best place for me. Here in the city it's the land of the white people. h4. Are there any luxuries or technology from the city that you will really miss?

There is technology that would be useful for the Yanomami. Technology that is not contaminated is good. For examples, solar panels, which act like a battery receiving energy from the sun. That's good for the communities, that helps us look after our health. Microscopes are good, and so are things like toothpaste. Things that you use to examine your heart are good. Also communications equipment, like two-way radios. Today our children are learning to use computers to send news to the city from the community. They also write up documents on the computer. For us indigenous peoples, those types of technology are important. h4. I am an anthropology grad student and a supporter of Survival International. I have certainly read a wealth of literature regarding the Yanomami in my studies and am very excited for this AMA. I have always wondered about Survival International (and others like it as well as anthropologists in the field) and its true impact on the lives of those it seeks to assist. Do many of the communities (yours included of course) feel that they are doing adequate work? If not what do these communities feel the organization (or its members as individuals) could improve upon in order to help educate other populations around the world.

The work of Survival is good work. They work very well defending indigenous peoples, and they also protect the places where Indians live. They spread the word, they're always giving lots of news. That's the role of Survival, and it's very good. Survival International was born because of the indigenous peoples. It's their cause. It's unique. The non-Indian people who support indigenous peoples, they can support indigenous organizations in their projects. h4. Pajé Kopenawa, good afternoon. I worked for an official organ of Human Rights along the Governo da Bahia, in Salvador a long time ago, and I must say that all of us Brazilians could have some more respect about the indigenous people, not only in the Amazon, but in the whole country. I don't think the government or the media let the people to be really aware of what's really going on around the indigenous territories. In your opinion, what could be changed for FUNAI to work better for you and what could be changed in the Brazilian media to help the rest of the people to understand better your people's affair?

First the government itself has to change. That's starting from the top of the government. Change the head of state, and then FUNAI can change to make its work better for indigenous people. It's the federal government that supports FUNAI, and it has to value FUNAI's work and give it money, especially for the indigenous territories that are not demarcated and to protect territories, which are already demarcated. FUNAI has to also protect the borders of indigenous territories to stop the invaders coming in. That is what is needed from FUNAI.

I think the media don't like to talk about the problems in Brazil. In fact, they like to hide them, so that other countries don't know about them. It would be really good if the TV, radio and internet could send out the real news so that we could communicate. h4. Can you describe the hardships that your tribe and other isolated tribes have experienced in the Amazon at the hands of prospectors, poachers and loggers? With the frontier continuing to consume the Amazon, do you think the truly isolated and uncontacted tribes, such as the Arrow People in the Vale do Javari, will survive long term into the future?

We indigenous peoples, we never forget our worries because the destruction is increasing - the search for gold and other minerals, the destruction of the forest for logging, and the non-indigenous population is getting bigger. We're worried about this. So where the indigenous peoples live, like the Yanomami, in fact it's not a lot of land, it's small. The ranchers are coming there, the gold miners, rural workers, mining companies, and many other people who don't have land. Although our territory has been demarcated, it's not guaranteed. So I'm very worried about our future.

I'm also very worried about our brothers and sisters who have not been contacted. In the Yanomami area there are uncontacted people called the Yawari. And on the upper Solimoes River there are other peoples who have not been contacted. They all speak different languages and are different peoples, but nevertheless they are going to suffer a lot - that's my worry. There aren't any non-Indians to defend them. FUNAI defends them, but FUNAI has no money. They don't have plans, they don't have trustworthy people, and they don't have the support of the government to give them the money in order to defend the uncontacted people. So in the future they're going to suffer a lot. h4. Thoughts on Napoleon Chagnon?

Napoleon Chagnon went to the Yanomami land to learn with us, and to know about our wisdom. Then he learned to speak our Yanomami language, and he changed his ideas, and he decided to play a trick on us. He asked communities to fight amongst themselves, he incentivized fighting, so that those who won in the fights would gain merchandise - pans, knives, etc. That's how Napoleon Chagnon worked. Then he sat down with his pen in his hand, saying that the Yanomami are violent. That is absolutely not the case. What is more violent is the United States, which has killed thousands of people - children, women - and destroyed cities, throwing atomic bombs. He has a lot of prejudice, Chagnon. He is prejudiced against my Yanomami people. Who is the most violent? Him. His people. Chagnon just said the Yanomami are violent without explaining anything. Some Yanomami, like other people, get angry. Every people on earth have their own fights. Men get jealous about women. Women get jealous about their husbands. Some women even beat their husbands. ALL human beings have this within them. h4. Hi Davi, there are some questions here about the 'developed world', but what do you think of the kind of development that is happening in the Amazon?

I think the development being done by the white people is done in the way of the non-Indians. They like building highways and hydroelectric dams for energy. They want to industrialize everything. They want to build great highways to transport things - all the minerals, wood - to other countries. The non-Indians like to do this. This is very bad for the indigenous people. In a sense, some of it is good - it brings in medicine and equipment for health and health teams who work with our communities. And airstrips help the health teams come in to help us. On the other hand it's not good. There are two paths, and the path of health is more important, but the other road is a huge road: the road of illness. It will bring lots of problems. The roads bring in alcoholic drinks, and bad things from the city. h4. How do you stop yourself from getting depressed about the future (of the Amazon, of the world…)?

When I'm in the city, I get very sad because I meet a lot of people who talk about the destruction of the Amazon. I feel even sadder when I hear about large-scale mining happening all around the world in indigenous territories. Those two things make me very sad. We don't know how to resolve this because the authorities are all united together to destroy nature. There are very few people who are defending and fighting together with indigenous peoples. So on the one hand I feel sad, but on the other hand I feel firm knowing that there are other people who will fight, who will protect our forest, who will protect indigenous peoples. I also trust very much in the forces of nature and the work of the shamans. I know that those who are destroying will suffer like we are suffering afterwards. Nature gives me courage so that I'm not sad all the time.

© Pablo Levinas/Survival

© Pablo Levinas/SurvivalDavi Yanomami in San Francisco.

I'm telling you this, so that you'll be happy knowing this. But I need help from the people of the United States. Keep watching, and if you want, support the indigenous organizations in our projects, and this will help conserve the Amazon rainforest. That's my message to you all. Obrigado.

Read more about the Yanomami tribe and how to support Survival's campaign for their rights:

Sign up to the mailing list

Our amazing network of supporters and activists have played a pivotal role in everything we’ve achieved over the past 50 years. Sign up now for updates and actions.