Gifts to all humanity

South American Indians’ most valuable, but totally unrecognised, contributions to humanity

Manioc

The root crop manioc, also known as cassava, is the woody shrub native to South America.

It was developed by South American Indians and has become an extremely important world food, providing the staple for about a billion people in over 100 countries, where the root supplies as much as a third of daily calories. In Africa alone, manioc is the staple food of nearly 80% of the population.

© istockphoto.com/Floortje/Mohamed Sadath

© istockphoto.com/Floortje/Mohamed Sadath

It is broadly divisible into sweet and bitter varieties, both of which are poisonous unless properly prepared. Many Amazonian tribes eat either the bitter or sweet type, but rarely both. Most grow dozens of different varieties; the Tucano alone cultivate over fifty.

Manioc grows in poor soil, is little bothered by drought and is a perennial crop, so can be harvested when required. It is now also used worldwide as an animal feed.

Manioc has saved countless lives already and will become increasingly important as the world’s poor grows in numbers.

Latex

The rubber tree, is the primary source of natural rubber, found in the northern part of South America.

Latex is the opaque, milk-like white or yellow, sticky or rubber sap from the tree that was discovered and developed by South American Indians.

South American Indians knew how to use latex long before Christopher Columbus arrived in the ‘New World’ in 1492, waterproofing their coats with latex and developing the rubber syringe.

The French explorer Charles de la Condamine, sent to South America by the Paris Academy of Science, wrote home in 1736 about the use of latex, saying ‘The Indians make bottles of it in the shape of a pear, to the neck of which they attach a fluted piece of wood. By pressing them, the liquid they contain is made to flow out through the flutes and, by this means, they become real syringes.’ Rubber items have been found among the excavations of the Mayan City of Chichén Itza.

© NASA

© NASA

Towards the end of the 19th century, the discovery of the process of the vulcanization of latex led to the ‘rubber boom’ sweeping through the Amazon, which wiped out 90% of the Indian population in a horrific wave of enslavement, disease and appalling brutality.

Latex can be sustainably tapped without harming the tree. Today, natural rubber is used to manufacture bouncing balls, boots, balloons and latex gloves, and is more suitable than synthetic rubber for the tyres of aircraft and space shuttles.

Tribal medicines

Were it not for the specialized botanical knowledge of Indigenous and tribal peoples, particularly those who live in the rainforests, many vital medicinal compounds might still be unknown.

It is thought that plants have been vital in the development of around 50% of today’s prescription drugs.

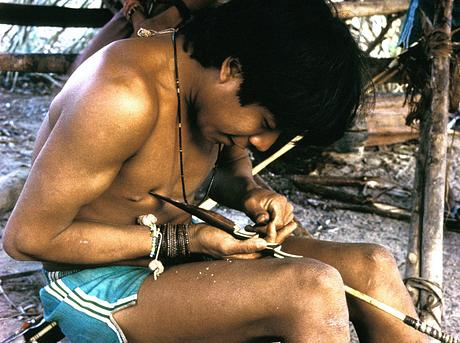

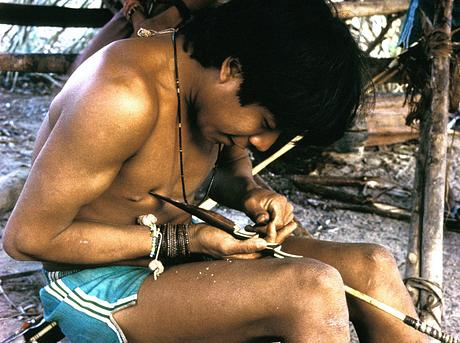

In South America, plant products used as poisons by Indians have become important in western medicine, such as ‘curare.’ Used on the tips of arrows to render prey immobile, it has been appropriated as a muscle relaxant has made possible such procedures as open-heart surgery.

Years of experimentation with their plants resulted in the Yanomami people of Brazil and Venezuela discovering that the juice of the woody cat’s claw vine relieves diarrhoea: studies in Europe have also revealed its efficacy in treating rheumatoid arthritis.

Thousands of miles away in North America, the manufactured painkiller aspirin was developed from the bark of the white willow tree, which American Indians boiled to treat headaches. The drug Taxol, an extract from the bark and needles of the Pacific yew tree, which was adopted by North American Indians for its immunity-building powers, is used to treat ovarian and breast tumours.

And in southern Africa, the Buchu plant, which has long been made into poultices for small wounds by Bushmen tribes, is known to help kidney and urinary tract diseases (as early as 1821, a London drug firm registered the plant as a remedy).