Wildlife conservation must support, not destroy, Indigenous Peoples

“Conservation” is destroying those who’ve nurtured their surroundings for timeless generations, writes Stephen Corry – the Indigenous Peoples who have actually fashioned those precious places that we now mistake as ‘natural’. It’s time for a new conservation ethic that recognizes them as senior partners – not as ’squatters’’ and ‘poachers’ to be evicted and criminalized.

Twenty years ago, fundraising publicity for the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) posed a very odd question: whether to send in the army or an anthropologist to stop Indigenous people destroying the Amazon rainforest.

Equally bizarre, it claimed that the media was “inundated with appeals to save native peoples” and asked, “Do they really deserve our support?” The world’s leading conservation organization went on by saying that tribes had learned many things from outsiders, including “greed and corruption.”

WWF’s answer to this apparent dilemma was thankfully not the army, but for concerned people to give it more money (its daily income is now $2 million) so it could “work with native peoples to develop conservation techniques.”

At Survival International, we were dismayed, and so were tribal organizations when we showed them the advertisement. For WWF to blame ‘duped’ tribespeople for deforestation was serious enough (giving the impression they trumped conservationists in attracting more funding was laughable), but even mentioning soldiers in the same sentence as conservationists uncomfortably echoed the latter’s dubious roots in colonialist ideology.

However WWF’s assertions are likely to have raised more eyebrows with its supporters than with many tribal people, for whom big conservation organizations have long been considered in the same bracket as development banks, road and dam builders, miners and loggers. All, they would say, are outsiders bent on stealing tribal lands.

Now the rhetoric has changed – but what about the reality?

Over the last 20 years, some conservation groups have at least cleaned up their language: their policies now make claims about working in partnership with local tribal communities, about consulting them and about how much they apparently support UN standards on Indigenous rights.

There are undoubtedly many in the conservation industry who believe all this, and who realize that tribal peoples are – as a broad principle – just as good conservationists as anyone else, if not considerably better.

Even those who disagree do at least recognize that alienating local people – whether tribal or not – eventually leads to protected areas being opposed and attacked. It’s one reason why the conservation industry makes much, at least on paper, of bringing local communities on board.

But apart from written policies, how much have things really changed in the last 20 years? Tragically for many, the answer is ‘not much’; in some places, they’re getting worse.

‘Voluntary relocation’ from tiger reserves

For example, the WWF-inspired tiger reserves in India are increasingly used to expel tribes from their forests so they can be opened up to tourism. The people are bribed with a fistful of rupees to give up the land, which has sustained their families for countless generations.

More often than not, promises are broken and they’re left with empty pockets and a few plastic sheets for shelter. Whether any financial incentives materialize or not, they are backed up with threats and intimidation.

Tribes are repeatedly told that if they don’t get out, their homes and crops will be destroyed and they’ll get nothing. When they finally cave in to this pressure, the conservationists call it ‘voluntary relocation’. Needless to say, it’s illegal.

It might surprise people to know there’s evidence that tigers thrive in the zones where tribal villages remain – the people’s small open fields encourage more tiger prey than in the enclosed forest. When they’re kicked out, their old clearings give way to roads, hotels and truckfuls of gawping tourists.

Studies show animal stress behavior increases with tourism. In other words, if you want happy tigers, then it’s much better to leave the tribal people where they’ve always been. They are surely the best eyes and ears to report any poaching activity anyway: Baiga villagers from the famous Kanha reserve respect the big cats as their ‘little brothers’.

Hunters or poachers?

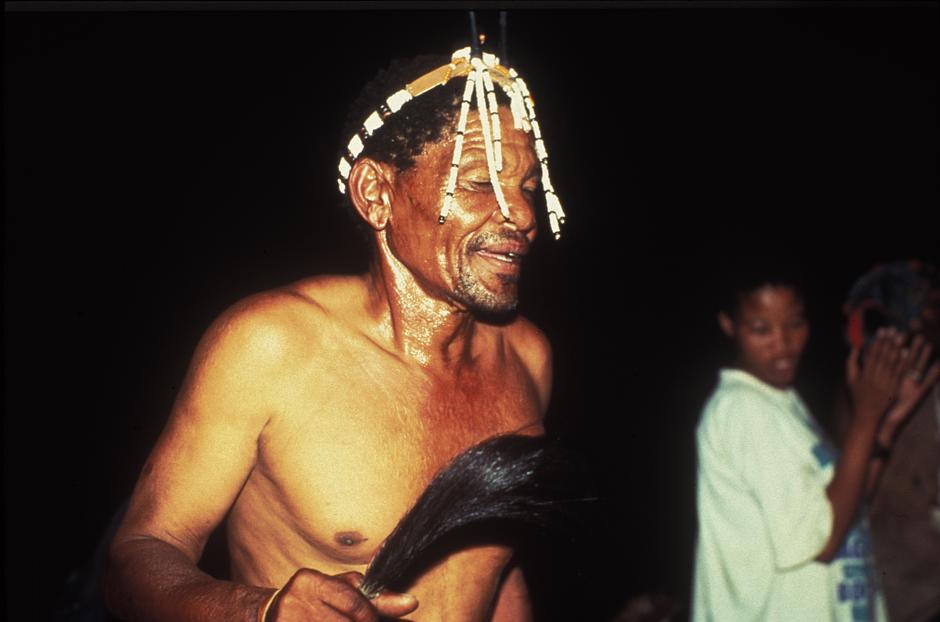

Guards in tiger reserves intimidate and beat tribespeople found on land that was once their ancestral forests. But at least they stop short of the torture to which the Baka ‘Pygmy’ people in Cameroon are subjected by anti-poaching forces.

To return to the advertisement: Conservation is sending in soldiers, just as it always has. Heavily armed, government paramilitary squads accompany ‘ecoguards’, equipped using WWF funds.

They beat those thought to have entered the protected areas – which are in fact Baka ancestral homelands. Tribespeople are assaulted even if they’re merely suspected of knowing those who have gone in. Meanwhile, their land is logged and mined – including by WWF partners.

A Baka man told us, “They beat us at the WWF base. I nearly died.” WWF seems incapable of stopping these abuses. It has known about them for years, but is scathing about those who denounce them: Survival’s “absurd” campaign to draw attention to them would, it claimed, help the “real” criminals.

Tribal victims are invariably accused of “poaching”, a term which now means any sort of hunting, including for food, with which conservationists disagree. That certainly doesn’t encompass all hunting. Many conservation organizations, including WWF, don’t oppose fee-paying big game hunting. On the contrary, they profit from it, even quietly whispering that it’s a vital ingredient in conservation.

Senior environmentalists are not averse to having a shot themselves. The former president of WWF-Spain – the previous king of Spain – was recently photographed in Botswana with his elephant kill. The resulting scandal forced him to step down, but only because the picture was leaked.

Kings can hunt elephants, which we’re told are threatened, but Bushmen can’t hunt to eat – not even a single one of the plentiful antelope they’ve lived off sustainably since time immemorial. If they’re even suspected of it, they’ll be beaten and tortured like the Baka.

This has been going on for decades, as the president of Botswana, Ian Khama, has tried to force all Bushmen out of their Central Kalahari region. In 2014, he banned hunting throughout the country – except for paid safari hunting of course. It was another illegal act in the guise of conservation.

Conservation and diamond mining

An avid environmentalist himself, and board member of Conservation International (CI) no less, General Khama claims he wants to clear the zone so that the wildlife will be undisturbed.

This is decidedly odd because the fauna has been much disturbed over the last 20 years, but not by the remaining tribespeople. Mining exploration continues apace and you will soon be able to buy a diamond mined from inside the so-called game reserve.

Due to go on sale around Valentine’s Day, these expensive love tokens now play a part in the destruction of the last hunting Bushmen in Africa.

In March, Khama is due to host the second United for Wildlife meeting – a consortium of the world’s major conservation organizations, including WWF and Conservation International (CI). A British royal will doubtless turn up and join the cry against “illegal poaching”. The assembly of conservationists, who routinely violate the law in their treatment of tribal peoples, will be hosted by a president guilty of trying to eradicate Bushmen hunters.

No doubt the hypocrisy will be lost in the sanctimoniousness with which the press will accord the photo ops. The first United for Wildlife meeting, in London, was also hosted by Princes William and Harry – both had returned the previous day from hunting in Spain.

A couple of years ago, to the southwest of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve diamond mine, another Bushmen community was going to be thrown off their land because they had the temerity to remain where CI had tried to establish a new ‘wildlife corridor’.

CI apparently has good policies, including having to consult the locals, so Survival International asked how it went about consulting with the Bushmen of Ranyane during its long, expensive Botswana study. Although the village is an easy four-hour drive from the nearest big town, CI admitted there had been no attempt to consult at all.

Conservation as a feel-good commodity

If this handful of examples surprises anyone, it’s because the industry has poured enormous resources into gaining a place among the world’s most trusted brands. This long PR exercise has involved blurring and hiding (rather than honestly confronting) conservation’s colonial, indeed racist, past.

Conservation has become a commodity, raising enormous sums of money, and rewarding supporters with an equally large feel-good factor, one that is nowhere near as straightforwardly apolitical as we are led to believe. Those who suggest ‘conservation’ might not really be as holy as some claim are routinely denigrated as blasphemers and apostates.

If the movement is to have any chance of achieving its stated objectives – which I, for one, pray it will – it’s vital that it’s scrutinized, questioned and exposed: for conservation casts an ideological opposition of nature versus people that is profoundly damaging to our real relationship with our environment.

By doing so, it harms both people and ultimately the environment, too; conservation destroys those who’ve nurtured their surroundings for timeless generations – people who have actually fashioned what we now mistake as natural. It works too often in direct opposition to its own goals.

When experts and researchers point this out, and criticize the industry, its common reaction is to try and silence them. For example, when award-winning German filmmaker and journalist, Wilfried Huismann, conducted a two-year investigation into the WWF, the film he produced, The Silence of the Pandas, was initially blocked through legal injunctions. You can read his book, PandaLeaks, though you won’t find it in mainstream bookstores. WWF’s legal team is very quick off the mark.

But many critics are committed environmentalists themselves. They too want to prevent the world’s most beautiful and diverse regions from being overrun by the industrialization that has destroyed so much and reduced so many people to poverty and dependency.

The problem is that the conservation industry is not only failing to achieve this; it can be working in the opposite direction. According to Huismann, WWF is turning a blind eye to the destruction of huge areas in Southeast Asia and South America for biofuel cultivation, requiring millions of gallons of toxic pesticides and herbicides.

Tribal Peoples are the best conservationists

If the conservation conglomerates really are to start preventing the further industrialization of these vital ecosystems, they surely must first remove giant polluters like Monsanto and BP from their own boards.

Conservation has to stop the illegal eviction of tribal peoples from their ancestral homelands. It has to stop claiming tribal lands are wildernesses when they’ve been managed and shaped by tribal communities for millennia.

It has to stop accusing tribespeople of poaching when they hunt to feed their families. It has to stop the hypocrisy in which tribal people face arrest and beatings, torture and death, while fee-paying big game hunters are actively encouraged.

The WWF publicity concluded, “Enough is enough” – I agree; it’s time for change. It’s obviously too late for those peoples whom conservation has killed, but what’s still going on today is illegal, immoral and does not deserve public support. Conservation has to wake up to the fact that tribal peoples are better at looking after their environment than anyone else.

Despite the millions pouring into the conservation industry daily, the environment remains in deepening crisis. It’s time to realize that there is a better way.

First, tribal rights have to be acknowledged and respected – are they not people too? Second, they have to be treated as the best experts at defending their own land. Third, conservationists must realize it’s they, themselves, who are the junior partners here, not the tribespeople.

The real creators of the world’s national parks are not the ideologues and evangelists of the environmental movement, but the tribal peoples who fashioned their landscapes with knowledge and understanding accumulated over countless generations.