Under threat from Canadian oil company

Though the Matsés have repeatedly opposed Pacific Rubiales’s work on their land, their protests have been ignored.

There are around 2,200 Matsés living on the Peru-Brazil frontier in the Amazon rainforest.

The Yaquerana river runs through the heart of their land, marking the international border that separates their home.

But to the Matsés, the streams, floodplains, and white-sand forests make up an ancestral territory that is shared by the entire tribe.

That is why we need space to grow our own food.

Browsing through the forest

Each community lives close to the riverbank, and every morning children and adults will set off to catch the day’s fish.

A wide variety of crops grow in their gardens, including staples such as plantain and manioc.

Chapo, a sweet plantain drink, is always on the boil in a Matsés home. Women cook the ripened fruit and squeeze its soft flesh through homemade palm-leaf sieves.

The delicious drink is then served warm by the fire, and most often drunk while swinging in a hammock!

Frogs for courage

One species of green tree frog known as ‘acate’ secretes a fluid that is used by both men and women for courage and energy, and to increase hunting ability.

Men collect the fluid by rubbing the frog’s skin with a stick. It is then applied onto small holes burnt into the receiver’s skin.

Dizziness and nausea soon make way to a feeling of clarity and strength that can last for several days.

Matsés men blow tobacco, or ‘nënë’ snuff up each other’s noses to give them strength and energy.

© isselee / 123RF Stock Photo

© isselee / 123RF Stock Photo © James Vybiral/Survival

© James Vybiral/Survival © James Vybiral/Survival

© James Vybiral/Survival © James Vybiral/Survival

© James Vybiral/SurvivalPlant spirits as medicine

To the Matsés, plants and animals have spirits just as humans do, and can ail or heal a human body.

A healer will identify the cause of his patient’s illness and treat it with its respective plant medicine.

A sore throat, for example, can be caused by eating howler monkey meat, and can be treated by a plant that resembles the monkey’s voice box.

Poison threats

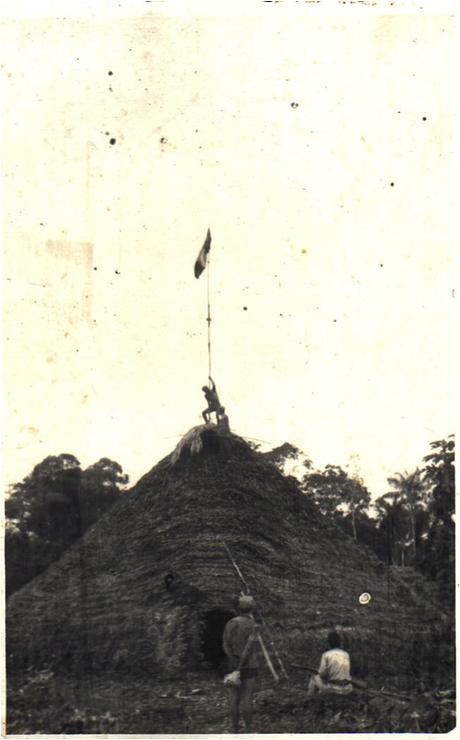

The missionaries arrived following violent clashes between local settlers attempting to build a road through the Matsés territory, and the Indians, who were defending their land.

Several of the settlers were killed after occupying one of the Matsés’ communal houses and raising the Peruvian flag, prompting the army to intervene.

The Matsés have since abandoned their communal houses for individual family homes, and many of their former ceremonies are no longer practised.

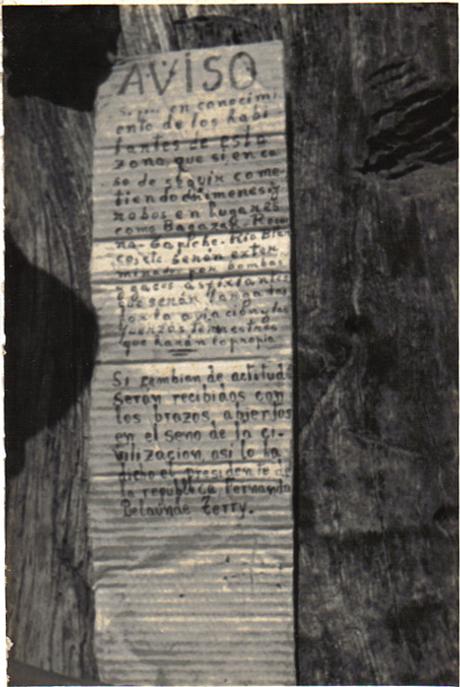

Warning to the inhabitants of this area: if you continue to steal and commit crimes…you will be killed with bombs and poison gas thrown from planes and by ground troops.

If you change your attitude, President Fernando Belaunde Terry says that you will be received with open arms into the breast of civilization.

Sign nailed onto a Matsés home by colonists.

The Matsés could not read.

© James Vybiral/Survival

© James Vybiral/SurvivalDuring the 1990s, loggers flooded into Matsés territory and the uncontacted Indians fled. Now the Matsés say the isolated people are coming back.

’When the loggers invaded our land, the uncontacted people disappeared from the forest. Now we have expelled the loggers and the Indians are returning.

The oil company will force them to flee once again….’

New threat from Canada

The explosions scare away animals, leaving little food to hunt. Drilling test wells is also likely to contaminate the rivers that Matsés use to hunt and fish.

It also allows companies to open up remote areas and set up camps. This increases the risk of contact, and causes the uncontacted Indians to flee.

The Matsés repeatedly opposed the company’s work and in 2016 and 2017, Pacific E&P withdrew from both concessions.

The Indians are now campaigning for both blocks to be cancelled and for no new contracts to be awarded to oil companies.

How we can help

In 2012, Peru promised to strengthen legal protection for the rights of its indigenous people, but it continues to permit oil exploration against the clear wishes of the Matsés.Tell the Peruvian government to protect uncontacted Matsés

Send an email to the Peruvian government

Join the mailing list

There are more than 476 million Indigenous people living in more than 90 countries around the world. To Indigenous peoples, land is life. Find out more about them and the struggles they’re facing: sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.

News from the Matsés

Victory! Canadian oil company pulls out of Matsés territory

Pacific E&P cancels its contract to explore for oil in the face of stiff opposition from the Matsés Indians

Proof of uncontacted Indians is serious blow to oil giant

Pacific Rubiales has already begun its dangerous work in an area proposed to protect uncontacted tribes

'Jaguar people's' urgent appeal to oil company's shareholders

The Matsés have urged shareholders of Pacific Rubiales to disinvest from the company to protect Peru's uncontacted tribes.

Amazon Indians unite against Canadian oil giant

Amazon Indians from Peru and Brazil have joined together to stop Canadian oil company destroying their land.