The words of Davi Kopenawa Yanomami

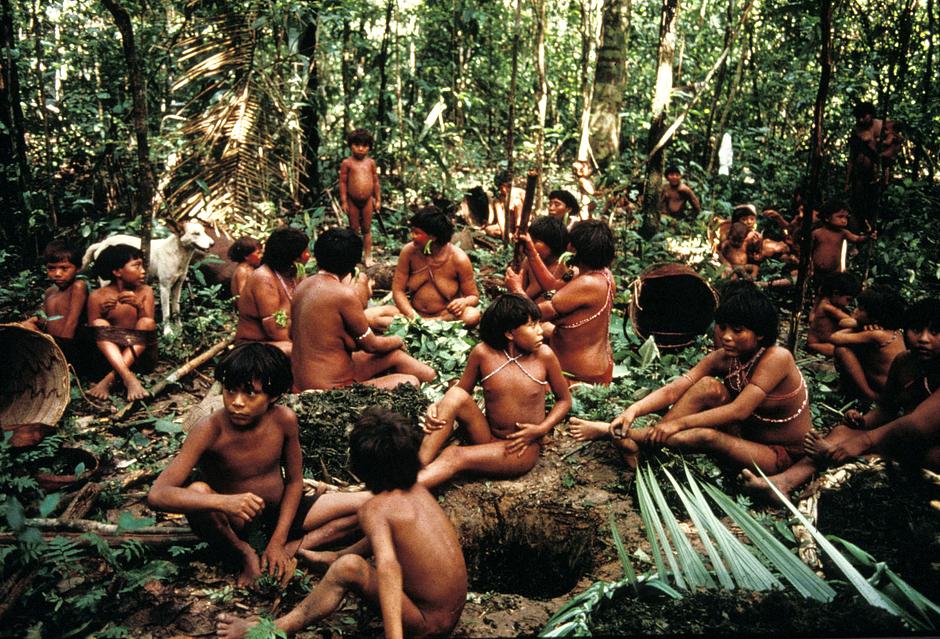

Davi Kopenawa Yanomami is a shaman from the Yanomami tribe. He is the only member of his tribe to have written a book, called The Falling Sky. The Yanomami live in the Amazon in Brazil and Venezuela, in the largest area of forest under Indigenous control anywhere on Ear

Discovering the white people

A long time ago, my grandparents, who lived on the headwaters of the

Toototobi River, sometimes visited other Yanomami established in the

lowlands along the Aracá River. It was there that they met white people for

the first time. During those visits our old ones got their first machetes. They

told me that many times, when I was a child.

But it was a lot later, when we lived at Marakana, closer to the mouth of the

Toototobi River, that the white people first visited our home. At the time our

old ones were still all alive and we were many, I remember. I was a boy, but

was beginning to become conscious of things. It was there that I started to

grow up and discovered the white people. I had never seen them, I knew

nothing about them. When I saw them I cried, I was so afraid.

The adults had already met them a few times, but I hadn’t! I thought they

were cannibal spirits that were going to devour us. I thought that they were

very ugly, whitish and hairy. They were so different they terrified me.

Besides, I couldn’t understand a single one of their entangled words. It

sounded like they spoke a ghost’s language.

The old ones used to say that they stole children, that they had already

captured some and taken them when they went up the Mapulaú River, in the

past. That’s also why I was so scared: I was sure that they were going to take

me away too. My grandparents had already told that story many times.

When those strangers would come into our house my mother would hide me

under a large basket in the back of our house. Then she’d say, ‘Don’t be

afraid! Don’t say a word!’, and I stayed there, trembling under my basket,

saying nothing. I remember it, but I must have been very small at the time or

I wouldn’t have fit under that basket! My mother would hide me because she

too was afraid that the white people would take me with them, like they had

stolen those children the first time.

Later I really began to grow up and to think straight, but I continued to ask

myself, ‘What are the white people doing here? Why do they open paths in

our forest?’ The older ones would answer, ‘No doubt they come to visit our

land in order to live here with us later!’ They understood nothing of the

white people’s language; that’s why they let them enter their lands in such a

friendly way. Had they understood their words, I think they would have

expelled them.

Those white people fooled them with their presents. They gave them axes,

machetes, knives, clothes. In order to make their distrust sleep they would

say, ‘We, the white people, will never leave you deprived of things, we will

give you many of our products and you will become our friends!’ But,

shortly thereafter, almost all of our relatives died in an epidemic, then in

another one. Later, a lot of other Yanomami again died when the highway

entered the forest and many more when the garimpeiros (gold prospectors)

arrived with their malaria. But this time I had already become an adult and I

thought straight; I really knew what the white people wanted when they

entered our land.

In the land of the white people

When I saw Europe, the white people’s land, I was distressed. Some cities

are beautiful, but the noise never stops. They run around in them with cars,

on the streets and even with trains underground. There’s a lot of noise and

people all over. One’s mind becomes dark and entangled, one can no longer

think straight. That’s why the thoughts of the white people are full of

dizziness and they don’t understand our words. All they say is, ‘We are very

happy to roll and fly! Let’s continue! Let’s look for oil, gold, iron!’ The

thought of those white is obstructed, that’s why they mistreat the land,

stripping it everywhere, and they dig it even under their houses. They don’t

think that one day it will end up collapsing.

We, we want the forest to be kept as it is, always. We want to live in it with

good health, and we want the xapïripë [shamanic] spirits, the game and the

fish to continue to live in it. We plant only the plants that feed us, we want

no factories, no holes in the ground, nor dirty rivers. We want the forest to

remain quiet, the sky to remain clear, the evening darkness to really fall and

for the stars to be seen.

The white people’s lands are polluted, they are covered by a smoke epidemic

that has extended very high to the sky’s bosom. This smoke is

coming towards us but has not reached us yet, because the celestial spirit

Hutukarari still repels it incessantly. Above our forest the sky is still clear,

because the white people haven’t been coming close to us for that long. But

later, when I’m dead, maybe this smoke will grow big to the point of

extending darkness over the earth and turning off the sun. The white people

never think of these things that the shamans know, that’s why they are not

afraid. Their thought is filled with forgetfulness.

Dreams of the origins

The xapiripë [shamanic] spirits have danced for the shamans since the

earliest time and continue to do so now. They look like human beings but are

as minuscule as particles of shining dust. In order to see them one has to

inhale the powder of the yãkõanahi tree many, many times.

The xapiripë dance together on great mirrors that come down from the sky.

They are never grey like the humans. They are always magnificent: their

bodies are painted with urucum [annatto paint] and lined with black

drawings, their heads are covered with white feathers of king vulture, their

beaded arm straps are full of parrot, cujubim [a type of bird] and red macaw

feathers, their waists are wrapped with toucan tails.

Thousands of them come to dance together, waving leaves of young palms,

emitting cries of joy and singing ceaselessly. Their path looks like spider’s

thread sparkling like moonlight and their feather ornaments move slowly at

the pace of their steps. It’s a joy to see how beautiful they are!

The spirits are so numerous because they are the images of the forest

animals. Everything in the forest has an utupë image: those who walk on the

ground, those who climb in the trees, those who have wings, those who live

in the water. It is those images that the shamans call and make come down to

become xapiripë spirits.

Those images are the true centre, the true interior of the forest beings.

Common people cannot see them, only the shamans. But they are not images

of the animals we know today. They are the images of these animals’

fathers, they are our ancestors’ images. In the First Time, when the forest

was still young, our ancestors were humans with the names of animals and

ended up becoming prey. It is them whom we kill with arrows and eat today.

But their images have not disappeared and it is they who dance for us as

xapiripë spirits.

White people draw their words because their thoughts are filled with

forgetfulness. We have kept the words of our ancestors within us for a long

time and we continue to pass them on to our children. The children who

know nothing about the spirits hear the chants of the shamans and then want

to see the spirits in their turn. This is how, even though they are very old, the

words of the xapiripë always become new again. It is they who increase our

thoughts. It is they who make us see and know far away things, the things of

the old ones. It is our study, which teaches us how to dream.