Iconoclasm and stopping the parks con

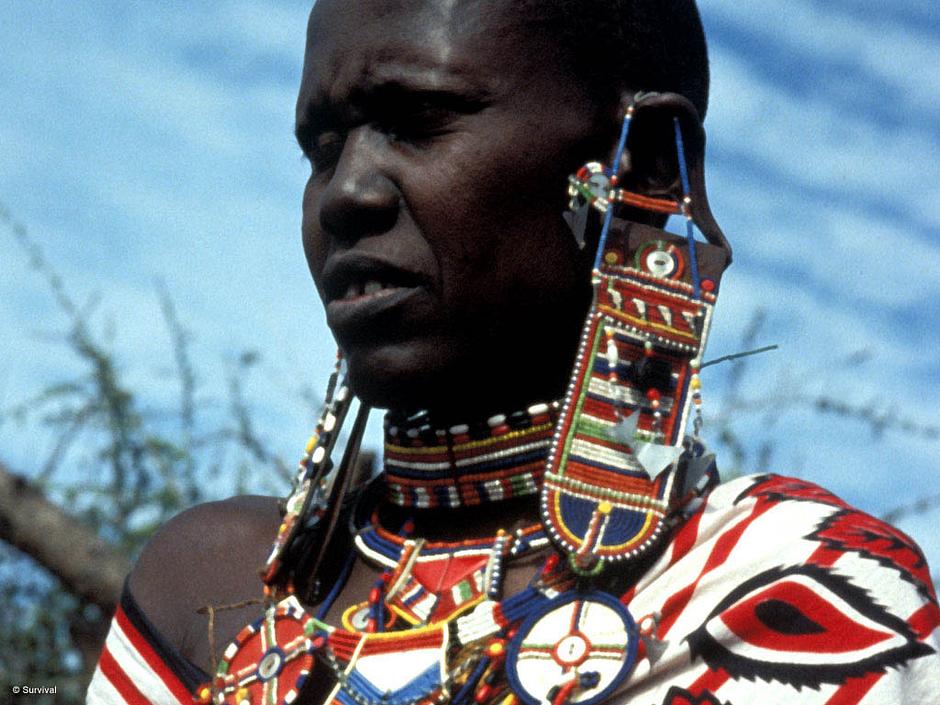

© The Newberry Library, Chicago

© The Newberry Library, ChicagoHow racist eugenics shaped the history of conservation.

By Stephen Corry, former Director

A version of this article was published as The Colonial Origins of Conservation: The Disturbing History Behind US National Parks in Truthout on August 25, 2015.

This is the second article in former Director Stephen Corry’s series on conservation. For a full list of all articles, please click here.

Iconoclasm – questioning heroes and ideals, even tearing them down – can be the most difficult thing. Many people root their attitudes and lives in narratives which they hold self-evidently true. So it’s obvious that changing conservation isn’t going to be an easy furrow to plow!

However, change it must. Its achievements don’t alter the fact that it’s rooted in two serious and related mistakes. The first is that it conserves “wildernesses,” shaped only by nature. The second is that it believes in a hierarchy, with superior, intelligent human beings at the top. Most conservationists once thought this was about “race.” Many still hold that they are uniquely endowed with the foresight and expertise to control and manage such “wildernesses” and that everyone else must leave, including those who actually own them and have lived there for generations.

These notions are archaic; they damage people and the environment. The second also flouts the law, with its perpetual land grabs. For nature’s sake as well as our own, it’s crucial to expose how these ideas grew and flourished, to understand just how mistaken they are. There’s an ongoing attempt to wipe from the map the quagmire around conservation’s wellspring, to pretend it’s all now transparent and sunlit. It isn’t.

Some conservationists, usually those lower in the pecking order, have the morality to face reality. They must prevail. With enough support, they will propel the industry from below towards a radically different approach, one which stands a far better chance of saving the environment and one which uses far smaller sums of money to do so.

This iconoclastic revolution is urgently needed and there’s no better time: 2015 is the 125th anniversary of Yosemite National Park, and 2016 completes a century for America’s National Park Service. They are highly symbolic anniversaries: Conservation dogmas were rooted in colonial conquest and were inextricably bound up in the genocide of Native Americans. Both lies, that of the wilderness and that of the inferiority of some human beings, were in full flower by 1916, though they were seeded earlier when America began to invent the parks model that is still, all too harmfully, exported around the world.

The movement really began with the 1864 Yosemite Grant Act: That spawned the belief which has become today’s crusade. As far as its gurus, like John Muir, were concerned, the Indians who had inhabited Yosemite for at least 6,000 years were a desecration and had to go. Muir deemed them lazy because their hunting techniques gave a good living without wasted effort. Such prejudice is alive and well today: An official in India said that tribal people don’t want to leave their forest because they get “fodder and income… for free” and are too lazy to work, so must be evicted.

White invaders saw the land as pristine wilderness because it didn’t conform to their European industrial image of productivity. In reality, Yosemite had long been an environment shaped by its inhabitants through controlled undergrowth burning, vital for its healthy forests with big trees and a rich biodiversity, tree planting for acorns as a food staple, and sustainable predation on its game, which ensured species balance.

In the 19th century, the newcomers didn’t hesitate to send in the army to police this wilderness and get rid of everyone else. One historian, Jeffrey Lee Rodger, is sympathetic to the cavalrymen but admits their “improvised punishments… were clearly extralegal and may have veered into arbitrary… force.”1 He might have compared such “punishments” with those still supported by conservation today, particularly in Africa and Asia, where tribal people are routinely kicked out of parks and beaten, even tortured, when they resist.

Native Americans were evicted from almost all the American parks, but a few Awahneechee were tolerated inside Yosemite for a few more decades. They had to serve tourists and act out humiliating “Indian days” for the visitors. The latter wanted the Indians they saw in the movies, so the Awahneechee had to dress and dance as if they were from the Great Plains. If they didn’t serve the park, they were out – and all did finally die or leave, with their last dwellings deliberately and ignominiously burned down in a fire drill in 1969.

© The Newberry Library, Chicago

© The Newberry Library, Chicago

As Luther Standing Bear declaimed, “Only to the white man was nature a wilderness… to us it was tame. Earth was bountiful.” The parks were and are supposed to preserve their “wilderness,” but they’ve never been very successful. In the case of Yosemite: over a thousand miles of often-crowded roads and hiking trails were constructed; trees were felled to make viewpoints; the balance of species was altered as animal and human predators were eliminated; trout were introduced to delight anglers; a luxury hotel was built; bear feeding areas were established to thrill visitors, so conditioning the animals to scavenge for human food; and hoteliers carried out a “firefall” for a century in which burning wood was pushed over Glacier Point to cascade thousands of feet into the valley (the scars remain visible nearly fifty years after it was halted).

The Indians’ own fires, their ancient practice of seasonal and controlled undergrowth burning, was stopped. One result is the devastating conflagrations which now plague California; those simply wouldn’t have happened on the Indians’ watch.

This wasn’t preservation, it was reshaping the environment to extract tourist dollars. In spite of this, and the fact that the National Park Service has presided over a loss of biodiversity and dozens of species extinctions, conservationists nevertheless think they’re better at protecting environments than the tribal peoples who live in them. That was in their DNA from conception and comes from the “scientific racism” and eugenics which were seeded five years before the Yosemite Grant, through Darwin’s seminal book, “The Origin of Species.”

Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton, later coined the word “eugenics” meaning controlling human breeding to maintain “racial purity.” For example, he decided the “inferior Negro race” was composed of “lazy, palavering savages” and, “average negroes possess too little intellect, self-reliance, and self-control to make it possible for them to sustain the burden of any respectable form of civilization.” It wasn’t just about “negroes” though, everyone had their place.

Galton rightly predicted that this “science” would become a new religion, and noted, “The feeble nations of the world are necessarily giving way before the nobler varieties of mankind.” Eugenics quickly grew into the scientific discovery to save civilization. Enthusiasts in Britain included writers H.G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw, who thought those who couldn’t “justify their existence” should be humanely gassed. John Maynard Keynes, William Beveridge, and Marie Stopes joined up, together with most of the liberal intelligentsia.

It’s pointless holding them to account. It was a time of social and cultural upheaval with “civilization” disintegrating in the unspeakable savagery of the world wars. On the other hand, it was always a matter of choice: However widely believed, eugenics always had a handful of formidable opponents.

In America, eugenics and conservation were born twins. Wealthy big-game hunters, including Teddy Roosevelt and his friend Madison Grant, both major conservationists, were among the most enthusiastic to embrace the racist creed. Their initial priority was to conserve the herds which provided their sport, and the easiest way to do that – so they thought – was to remove the predators who were killing the game to eat (and for its leather) rather than to hang horns on the wall. The predators were principally humans, Native Americans as well as poor colonists trying to eke a living from an unfamiliar world.

Ousting the predators had the opposite of the desired effect. Elk herds in Yellowstone, for example, were to grow beyond the carrying capacity of the land. (The same is happening now, with elephants in Botswana.)2 Weak animals, once the first to fall from hunter’s arrow or wolf’s fang, started reaching reproductive age. The herd grew, but the animals sickened as hunger took its toll. Seeing their precious trophies fading through their bungling, the elite came up with ideas of “game management” still applied today. The key is to cull, keeping the herd smaller but stronger.

They then turned their attention to the human “herd,” which was expanding rapidly from European immigration. Following Galton, they categorized humankind into hierarchical “races” and feared the country being swamped by the lower types – “Mediterraneans,” “Alpines,” and Jews.

The big-game hunting boys saw themselves as a different ilk. They were the “Aryans” from northern Europe, the creators of true civilization, science, culture, religion and wealth, the heroes who improved the world rather than the shorter, darker spongers who just took. Racial mixing would, they were convinced, eventually threaten the disappearance of their race and its unique, irreplaceable talents.

The ultimate responsibility bore on their shoulders – how to save the world. Europe was already hopelessly mixed, but they could control the United States. They legislated to reduce immigration from “non-Aryan” countries, they outlawed “interracial” marriage, and imposed segregation wherever possible, and they compulsorily sterilized anyone they could get their hands on who didn’t fit their bill; no one with a mental, physical, or even social, problem was safe, particularly the poor.

The most important hunter turned conservationist, Madison Grant, was also their principal writer. He was a key supporter, often founder or leader, of a dozen or so conservation groups which still exist, though he barely appears in their official histories. Among the most prominent were: Save the Redwoods League; the New York Zoological Society (now the Wildlife Conservation Society, WCS); and the National Parks Association (now the National Parks Conservation Association).

His book, “The Passing of the Great Race,” was published in the year the National Park Service was founded. Science Magazine’s glowing review enthused over its “solid merit.” Thirty years later, it would be cited by German Nazis who couldn’t understand why they were on trial: They were, they pleaded, simply emulating the United States where scientific eugenics had long been used to shape society. Grant had sent a translation of his book to Hitler, who called it his bible.

It’s unfair to single out Madison Grant. Scratch the record anywhere in the early conservation movement and eugenics sounds loud and clear: Alexander Graham Bell, who falsely claimed to have invented the telephone, and who was one of the founders of the National Geographic Society; two charter members of the Sierra Club, David Starr Jordan (founding president of Stanford University) and Luther Burbank, were all prominent members of the movement. George Grinnell, founder of the Audubon Society (and Edward Curtis’s mentor) was Madison Grant’s close friend for nearly fifty years. The National Park Service’s first director, mining magnate Stephen Mather, was backed by Charles Goethe, of the Audobon and Kenya Wildlife Societies, regional head of the Sierra Club, and outspoken advocate of Nazi eugenic laws.3 In one article Goethe enthused, “We are moving toward the elimination of humanity’s undesirables like Sambo, the husband to Mandy the ‘washerlady’.”4 In 1965, on his 90th birthday, Goethe was dubbed the state’s “number one citizen” by California’s Governor. He fought against immigration from Mexico whose inhabitants, he pontificated, scored as low as “negroes” and Italians in IQ tests.

Eugenics grew into the establishment belief of the first half of the 20th century and didn’t falter seriously until 1945 when an American battalion stumbled into Buchenwald, just after its inmates had seized it from fleeing camp guards.

When the Nazis had built it, their second concentration camp, an oak tree growing inside its fences had consciously been conserved. It was symbolic, though not about nature: Goethe had written poetry, including some of Faust, under its branches.

© Delarbre Léon

© Delarbre Léon

The military defeat of Nazism was to unveil scientific eugenics as a true Faustian pact, absurdly false and grotesquely savage. That should have been its end. But as with much in this history, the fog of obfuscation hangs over the landscape: Eugenic affiliations are continually denied or censored.

Acclaimed figures in post-war European conservation included former Nazis like Prince Bernhard, a founder of WWF (who joined the allies before the war), and Bernhard Grzimek, the self-proclaimed “savior of the Serengeti,” co-founder of Friends of the Earth Germany, and former director of the Frankfurt Zoological Society – one of Europe’s biggest conservation funders. He made sure the Maasai and other tribes were expelled.

So did Mike Fay of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), the creator of the Nouabalé-Ndoki Park in the Congo, which kicked out Mbendjele “Pygmies,” using American taxpayers’ money. WCS trained the guards who now beat Mbendjele for suspected poaching. Fay has even, privately, suggested that vaccinating tribal children would result in them growing up into more poachers. Given the way they’re treated, it’s frankly not surprising that those who once lived on and from the land “poach” if the opportunity arises: Conservation breeds poachers.

When today’s environmental leaders press for curbs on immigration and population it can only call to mind this dark past. Did David Brower, for example, founder of both Friends of the Earth and Earth Island Institute, have to assert that having children without a license should be a crime – given that he had four of his own?

Few environmentalists protest at the theft of tribal lands or stand for Indigenous rights. For example, John Burton, of the World Land Trust, formerly of Friends of the Earth, and Fauna and Flora International, openly opposes the very idea, though other key players, some in Greenpeace for example, have signaled support for tribes.

The unexpurgated history of conservation matters because it still colors attitudes towards tribal peoples. Conservationists no longer pretend to be saving their “race,” but they certainly claim to be saving the world’s heritage, and they mostly retain a supercilious attitude towards those they are destroying.

Such attitudes must change. Conservation, nowadays particularly in Africa and Asia, seems as much about land grabbing, and profit, as anything. Its quiet partnerships with the logging and mining industries damage the environment. Tribespeople are still abused, even shot, for poaching when they’re just trying to feed their families, while “conservation” still encourages trophy hunting. The rich can hunt, the poor can’t.

In spite of the growing evidence to the contrary, many senior conservationists can’t accept that tribal peoples really are able to manage their lands. They’re wrong. It’s a great con trick and it’s time it was stopped.

Other conservationists are keen to do better. They deserve to know there’s a groundswell of public support behind them, pushing for a major change in conservation to benefit, finally, tribal peoples, nature, and us all.

Stephen Corry is the former director of Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights. The organization has a 46-year track record in stopping the theft of tribal lands. It is working to change conservation and asking people to join its “Stop the Con” campaign.

Footnotes

1 Jeffrey Lee Rogers, How the Cavalry Saved Yosemite, in Yosemite: a storied landscape.

2 As borne out by the following articles: https://www.fitzpatrick.uct.ac.za/publications/Cumming_Jones_2005.pdf and https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2013/04/2013416113911163191.html and https://commonwealth-opinion.blogs.sas.ac.uk/2013/botswanas-jumbo-dilemma-the-expanding-elephant-population-and-the-environment-by-keith-somerville/

3 In 1937 he wrote to Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer, director of “racial hygiene” in Frankfurt, saying, “I feel passionately that you are leading all mankind herein.” Verschuer was doctoral supervisor and collabator of Josef Mengele, infamous for his barbaric experiments on children in Auschwitz. He continued to excel after the war, as professor of genetics at Münster. Allen, Garland E, “Culling the Herd”, Journal of the History of Biology, 2012

4 “Patriotism and Racial Standards.” Eugenical News 21(4), 1936.