Straddling the borders of Peru, Brazil and Bolivia is the Uncontacted Frontier – home to more uncontacted tribes than anywhere else on the planet.

Where their land is intact, they are thriving.

But elsewhere, oil exploration, loggers, drug-traffickers and roads are putting their lives on the line.

Survival is calling on the three governments to uphold the law and prevent their destruction.

On the border of Peru, Brazil and Bolivia lives the highest concentration of uncontacted tribes on Earth. They know no borders, crossing between countries as part of their nomadic routes. They include the Isconahua, Matsigenka, Matsés, Mashco-Piro, Mastanahua, Murunahua (or Chitonahua), Nanti, Sapanawa and Nahua, and many more whose names are unknown.

Not much is known about them. But we do know that they have rejected contact, often as a result of horrific violence and diseases brought in by outsiders.

Some chose isolation after surviving the rubber boom, in which thousands of Indigenous people were enslaved and killed. Many fled to the deepest parts of the Amazon and have evaded long-term contact ever since.

On the very rare occasions when they are seen or encountered, they make it clear they want to be left alone.

Sometimes they react aggressively, as a way of defending their territory, or leave signs in the forest warning outsiders to stay away.

How they live

These uncontacted tribes are not backward and primitive relics of a remote past. They are our contemporaries and a vitally important part of humankind’s diversity.

Almost all are nomads, moving throughout their territories according to the seasons in small, extended family groups.

In the rainy season, when water levels are high, those who generally do not use canoes live away from the rivers deep in the rainforest.

During the dry season, however, some camp on the beaches and fish and collect turtle eggs.

Some live in communal houses and plant crops in forest clearings, while also hunting and fishing.

Others, such as the Mashco-Piro, are hunter-gatherers who can quickly build camps and abandon them. They hunt animals such as monkeys with long bows and arrows.

Outsiders are moving in

There are many outsiders who seek to force contact in the Uncontacted Frontier.

Missionaries, for example, want to evangelize tribal people as they consider them to be primitive.

Some academics are calling for uncontacted tribes to be forcibly contacted as they consider their existence to be “not viable in the long term”.

Other intruders have shot the Indigenous people, and even massacred whole villages, when engaged in illicit activities such as drug trafficking.

Very often, however, contact occurs simply because outsiders want to steal the tribes’ lands and resources. Tribal peoples are the best guardians of the environment and as a result, their lands are resource-rich. The timber from their forests is incredibly profitable. So too is the oil and gas that lies beneath their feet.

These threats have ripple effects throughout the region as the uncontacted people are forced to abandon their gardens and hunting grounds and flee.

For example, a group of Sapanawa recently made contact in Brazil after outsiders massacred the majority of their elderly. So many people were killed that they couldn’t bury them all and their corpses were eaten by vultures.

Fatal first contact

Survival opposes attempts by outsiders to contact uncontacted people. It’s always fatal and initiating contact must be their choice alone. Those who enter uncontacted tribes’ territories deny them that choice.

Whole populations are being wiped out by diseases like flu and measles to which they have no resistance. The young and elderly are often the first and most likely to die.

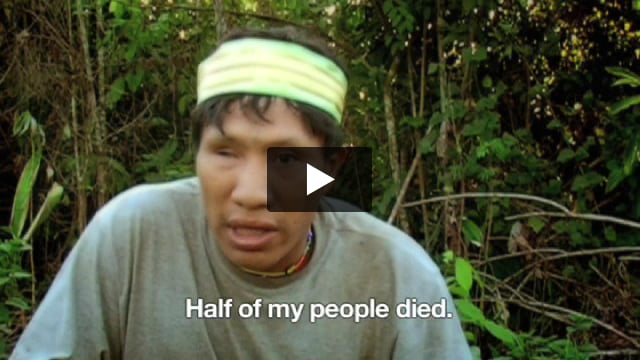

First contact with the Matis in the Javari Valley in Brazil ocurred in 1978 and rapidly killed over half of them. They stopped practising their ceremonies and, like many Indigenous people suffering from the trauma of first contact, stopped having children. By 1983 only 87 Matis survived. Today the shattered remnants of the Matis are regrouping but suffer from the impacts of introduced diseases such as malaria and hepatitis.

In the early 1980s, exploration by Shell led to contact with the isolated Nahua tribe. Within a few years around 50% of the Nahua had died. To this day, the surviving Nahua suffer from a variety of diseases such as tuberculosis and Hepatitis B, and receive little help from the government.

The problems do not stop after contact. Sometimes governments try to forcibly integrate and mainstream indigenous peoples by settling and integrating them. Officials believe that the tribes need “modernizing” but the fact that these societies are not industrialized does not mean they are not already part of the modern world, with just as much right to choose the way in which they live as any other society.

The underlying objective, however, is to free up indigenous land so that the resources can be used.

Protecting the land

All uncontacted tribal peoples face catastrophe unless their land is protected. This means that all of the Uncontacted Frontier region must receive protection. Survival is doing everything it can to secure the uncontacted tribes’ land for them, and to give them the chance to determine their own futures.

Several uncontacted reserves, indigenous territories and national parks exist in this region. But this is not enough. More must be created so that all tribal territory is included inside a protected area.

And, most importantly, the borders of these areas must be properly policed. For example, the Brazilian government has recognized territories for uncontacted tribes in this region. However, cuts in funding mean that monitoring posts are understaffed and even abandoned which has enabled drug traffickers and loggers to operate on uncontacted land with impunity.

Furthermore, oil exploration and roads continue to be approved in the very hearts of these protected lands.

Sierra del Divisor: The Watershed Mountains

A newly created park in Peru has failed to protect the uncontacted people living inside.

The Sierra del Divisor region straddles both Peru and Brazil. It is known for its unique landscape and is a stronghold for rare and endangered animals.

It is also home to a number of uncontacted tribes, including the Matsés and Isconahua.

In 2015, a national park was created on the Peruvian side. But the region continues to be overrun by loggers, drug-traffickers and miners.

Despite being a national park, large areas can still be opened up to oil exploration. Any oil exploration is devastating for uncontacted peoples and forces them to run for their lives.

Tribal peoples are the best conservationists. Protecting them is therefore the best way to protect the environment, for all humanity.

When contact is made

When members of a tribe initiate contact, or contact is forced upon them by outsiders, the country’s government has an obligation to react swiftly and decisively to try and reduce the very high risk of loss of life.

Expert medical teams must travel to the area immediately and remain in situ on a long-term basis. Care must be taken not to encourage the tribal peoples to become dependent.

The boundaries of the uncontacted peoples’ territories should be policed to prevent incursions by unauthorised people. The latter must also be kept away if tribespeople have voluntarily left the borders of their own land.

Contact must not be initiated by anyone other than the tribe in question, as nearly all contacts result in loss of life.

Mashco-Piro

In 2011, outsiders began to regularly make contact with a group of Mashco-Piro. These outsiders included missionaries and tourists, who gave members of the tribe objects such as machetes, plantain and clothes.

The Peruvian government did not stop these interactions until 2015, after the Mashco-Piro killed a man in a local indigenous community.

The government now monitors the tribe to ensure that there is no more violence and to prevent the spread of disease. However, there is minimal medical presence and disaster could strike at any moment.

Help Survival

All of the Amazon Uncontacted Frontier must be protected if the tribal peoples who live there are to survive.

Their territories should never be opened up to outside projects, including oil exploration, deforestation and roads.

We’re doing everything we can to secure their land for them, and to give them the chance to determine their own futures.

Act now to support the Uncontacted Frontier

Your efforts are crucial in defending the tribes living in the Uncontacted Frontier. Take action now!

Join the mailing list

More than one hundred and fifty million men, women and children in over sixty countries live in tribal societies. Find out more about them and the struggles they’re facing: sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.

News from the Uncontacted Frontier

Peru passes law approving Amazonian “death roads”

Roads will open up the Amazon home of the highest concentration of uncontacted tribes on Earth.

Amazon Indians plead for help after “massacre”

Brazilian Indians have appealed for global assistance to prevent further killings

Genocide: goldminers “massacre” uncontacted Amazon Indians

Around 10 uncontacted tribespeople reportedly murdered in Uncontacted Frontier

Gillian Anderson and Mark Rylance launch global campaign for uncontacted tribes

Survival ambassadors star in new film for rights of world's most vulnerable peoples

Brazil: Government abandons uncontacted tribes to loggers and ranchers

Government cuts could leave uncontacted tribes and their land fatally exposed to invaders

Exclusive: Oil company pulls out of uncontacted tribes’ land under pressure from Survival

Canadian corporation pulls out of uncontacted land in the Peruvian Amazon with immediate effect, after Survival campaign