Tribal Olympians

Survival reveals some of the astonishing skills of the world’s tribal peoples, from the Awá archers of the Amazon to the Bajau divers of Borneo.

A young boy with home-made wooden goggles grasps the tail of a tawny nurse shark as it pulls him through the shallow waters of the South China Sea.

The Bajau people of Sabah, Malaysia, can free-dive up to 20 metres deep when hunting for fish, pearls and sea cucumbers on the sea-bed.

Known as ‘sea gypsies’, the Bajau spend most of their lives at sea; when they free-dive, they can hold their breath for up to three minutes.

Scientists have discovered that the Bajau are submerged for up to 60% of the time they spend in the water, which is nearly as long as a sea-otter.

© James Morgan/Survival

They move through the rainforest at night, carrying torches made from resin.

The Awá people of the Brazilian Amazon, Earth’s most threatened tribe, are expert archers.

Awá men hunt with bows up to 1.85 metres long and carry a bundle of arrows made from bamboo, palm fibre, tree resin and bird feathers. Arrow heads vary in shape and size according to the type of prey.

While waiting for howler monkeys to appear, hunters sit in the branches of trees up to 30 metres from the ground. Arrows are shot at the target from this dizzying height.

Today the Awá forest is being cut down faster than that of any other tribe in the Amazon; they will only survive if their land is protected.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

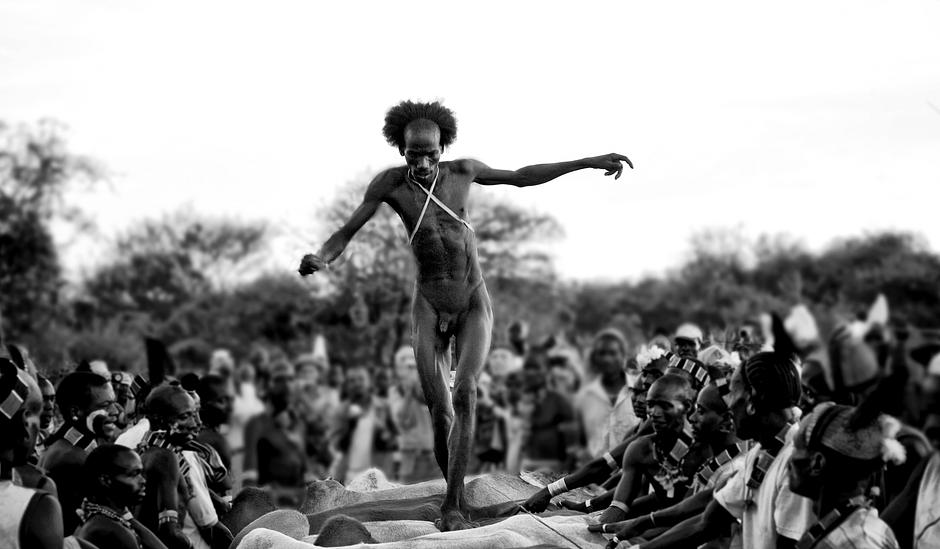

For the Hamar, a tribe from the Lower Omo Valley in Ethiopia, the ability to leap over a line of cattle qualifies a man to marry, own cattle and have children.

Before he jumps, a man’s head is partially shaved and his body smeared, for strength, with dung – as are the cattle, to ensure their slipperiness. Failure to leap across the line of bulls and cows can bring shame, but further attempts are allowed.

The lower valley of the Omo River is believed to have been a cultural crossroads for thousands of years, where a vast diversity of migrating peoples have converged.

Today, however, construction of a giant hydroelectric dam threatens to block the river, end the Omo’s natural flooding cycles and jeopardize the tribes’ sophisticated flood-retreat cultivation methods.

© Mario Gerth/Survival

The ocean is our universe, said Hook Suriyan Katale, a Moken man from the Surin Islands.

The semi-nomadic Moken, who live in the Mergui Archipelago in the Andaman Sea, are said to be able to swim before they can walk.

A scientific study conducted by Sweden’s Lund University showed that the eyesight of Moken children is 50% more powerful than that of European children.

Over hundreds of years they have developed the unique ability to focus under water, using their visual skills to dive for food on the sea floor, thus stretching the efficacy of their eyes to the limits of what is humanly possible.

© Cat Vinton/Survival

High in the canyons and deserts of Mexico’s Sierra Madre mountains, long-distance endurance running is a way of life for the Rarámuri, or Tarahumara people. The name Rarámuri is, in fact, thought to mean those who run fast.

The most popular Tarahumara running game is ŕarajípar, or kick-ball racing, in which men flip a wooden ball with their feet. Major races may last for 48 hours, covering a distance of between 150-300 kilometres over rugged, high-altitude terrain.

© Jay Dunn (www.MexicoCulturalCalendar.com/Survival)

In southern Papua, a few degrees south of the Equator, there are no roads in the coastal homeland of the semi-nomadic Asmat people.

As a result, the Asmat have long used canoes to journey along the extensive network of deep, wide rivers that run through their rainforest.

Canoeists propel and steer while standing, their skill lying in maintaining their balance as they dip and sweep long tassled blades through the tidal waters; a particularly difficult and dangerous task when cross-currents are created from rivers flowing into the Arafura Sea.

All Papuan tribal peoples have suffered greatly under the Indonesian occupation, which began in 1963, and is almost unparalleled in its brutality.

© JEANNE HERBERT

Mongolians define themselves as the people of five animals: horses, sheep, goats, camel and cattle. Horses are prized above all others – one horse is traditionally worth ten goats – and are still an integral part of daily nomadic life.

The national drink, airag, is made from fermented mares’ milk; strands of horse-hair are used as ties in nomads’ homes, or gers.

Their equestrian skills are exceptional; boys are often taught to ride as soon as they can walk, learning on silver-engraved leather saddles that are passed down the generations.

During the naadam festival, boys as young as 5 years old race bareback and shoeless across the Mongolian steppe for up to 30 kilometres.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

In the shimmering heat of the Central Australian desert, Pitjantjatjara Aborigine children flip and twist in a display of exuberant acrobatic skills.

The astonishing skills of tribal peoples are not only a measure of just how swift, high and strong we can be as humans – where our physical and mental limits lie – but an indicator of the extraordinary diversity of mankind.

As the western world becomes increasingly homogenized, sedentary and divorced from nature, we can all learn from tribal peoples. They have thrived for thousands of generations relying solely on their own resources, and their ways of life are still largely sculpted by their natural environments.

Tribal peoples can play a vital role in tomorrow’s world, says Stephen Corry, Director of Survival International. They show us who we are in relationship to others and the animals, plants and Earth which surround us. They also demonstrate, in their diving, hunting, running, riding and swimming accomplishments, what it is to be agile, adaptable and resourceful.

In short, they show us what it is to be human.

© Alastair McNaughton/www.desertimages.com.au

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...