'Mother'

The words ‘Aiya’, ‘Ngu’ and ‘Anaanak’ have the same meaning in different tribal languages: Mother. This gallery portrays the lives of tribal mothers, their babies and the lands on which they raise they children.

In the Congo Basin, a ‘pygmy’ mother carries her baby while she gathers wild plants and nuts in the forest.

For many tribal peoples, the concept of ‘Mother’ refers not just to a parent who gives life and supplies food, shelter and love, but also to their lands – the rainforests, grasslands, deserts and mountains that are their homes also provide the material and spiritual sustenance they need to survive.

These bonds are strong. When the cord is severed – through colonization, forced eviction, mining, logging or other ‘development’ reasons – the consequences can be devastating.

Survival International has campaigned for 40 years to protect the lands and rights of tribal peoples.

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

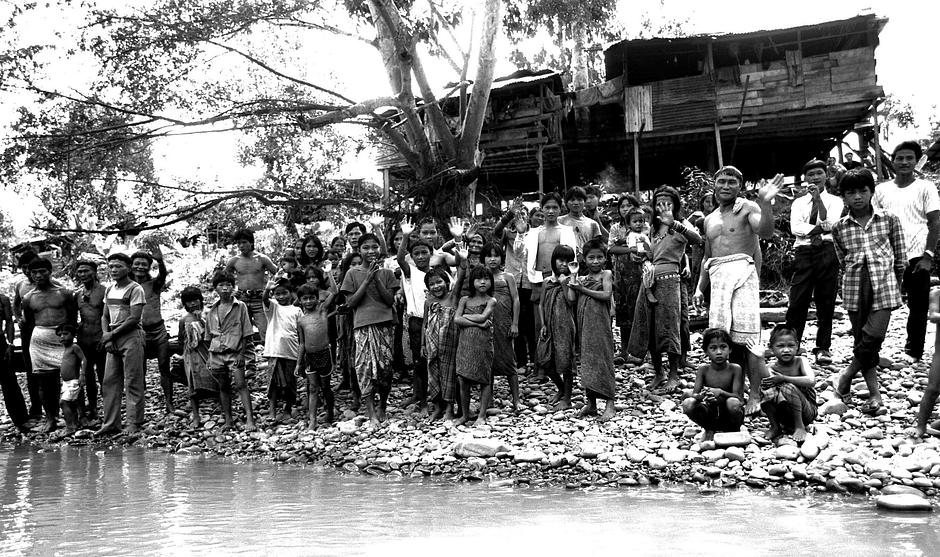

A Penan community in Sarawak, Malaysia.

Many tribal children have lived, and still live, in complex communities, where they grow up knowing a greater intimacy with a larger number of individuals, and people who look after them, than most city dwellers.

Values have evolved that place the collective over the individual – many tribal children are taught that sharing is a fundamental tenet of social life, and community decisions are made by consensus.

© Andy Rain/Nick Rain/Survival

Far above the Arctic Circle, a Nenets reindeer herding woman and child stand outside their chum (tipi) on the Yamal Peninsula, a stretch of peatland that extends from northern Siberia into the Kara Sea.

Nenets women traditionally gave birth in their chums, and made diapers from cloth filled with moss. Today, they more commonly give birth in hospitals, having been collected by helicopter.

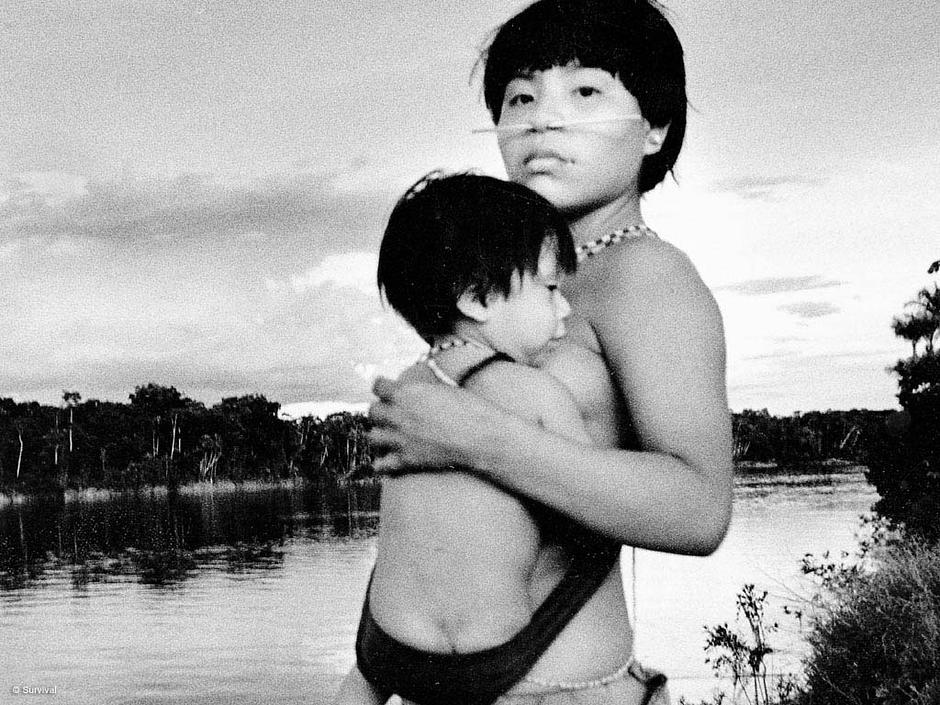

A Yanomami woman and child on the banks of an Amazonian river.

For many tribal societies, childbirth is usually regarded as an everyday event, attracting no fanfare, with little special attention given to either baby or mother, says Stephen Corry, Director of Survival International.

Yanomami women normally leave their shabono (communal houses), accompanied by their mothers or other older female relatives, in order to give birth in the rainforest. Most Yanomami women carry their child in a sling, made from cotton or strips of a fiber plant such as banana, for up to two years.

They breastfeed their children until they are several years old, a practice which is known to inhibit conception.

© Steve Cox/Survival

Just south of the Equator, between the soda waters of Tanzania’s Lake Eyasi and the ramparts of the Great Rift Valley, live the Hadza, a small tribe of hunter-gatherers: one of the last in Africa.

Until the 1950s all Hadza survived by hunting and gathering. Today, only 300 – 400 of a population of approximately 1,300 Hadza are still nomadic hunter-gatherers, gathering most of their food from the bush, while the rest live part-time in settled villages.

When the Hadza were more nomadic than they are today, childbirth sometimes occurred on the move, even in the hollowed out trunks of ancient baobab trees. The mother would then simply carry the baby and walk on to catch up with her family.

© Jean du Plessis/Wayo Africa

A Bodi boy in Ethiopia carries his goat; at a young age, they also learn poems that they sing to their favorite cows.

The first, and completely dependent, stage of life does not last long for most tribal children, says Stephen Corry. By the age of four or five, children start to join adult activities: boys hunt or tend livestock, girls look after smaller children and help at the hearth or in food gathering.

In Malaysia, Penan children help to build homes from tree saplings; beneath the blue-green surface of the Andaman Sea, Moken children learn to catch dugong and sea-cucumber with long harpoons; on the grasslands of Mongolia, Tsaatan children’s parents teach them the ancient herding skills of corralling reindeer.

© J

Young Yanomami boys learn to ‘read’ the spoor of animals, use plant sap as poisons and shin up trees by tying their feet together with liana vines.

In those days, my Mother always took me with her into the forest to look for crabs, fish with timbó, or gather wild fruits. I would also go with her to the fields when we needed to harvest cassava, bananas, or to cut firewood. Sometimes the hunters would also call me at daybreak when they left for the forest.

That was how I grew up in the forest.

Davi Kopenawa Yanomami, Brazil.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

A young Asháninka mother, wearing a traditional kushma robe, plays with her baby daughter in Acre state, Brazil.

Pregnant Asháninka women refrain from eating turtle meat for fear it will make their child slow.

Asháninka children also learn self-sufficient skills, such as hunting and fishing, at an early age.

© Mike Goldwater/Survival

Inuit infants are carried by their mothers in an amautik for the first year or two of their lives.

An amautik was traditionally made from caribou fur, with the fur facing in, so the baby lay in its comfort and warmth. Today, they are also made from duffel and other materials.

‘After feeding, the baby girl dozes. With words of welcome, she is lifted into the amautik, the pouch shaped into the hood of her mother’s parka, where she can lie curved against her mother’s back. The baby’s mother smiles, holding her daughter for her father to adore, and says, ‘Anaanangai. Ii, anaanagauvutit.’ ‘Mother? Yes, you’re my mother.’ … For she is a baby who carries the atiq, the spirit and name, of her late grandmother.’

Hugh Brody, from The Other Side of Eden: Hunters, Farmers, and the Shaping of the World.

© Ansgar Walk/Creative Commons

Gentle, compassionate and religiously tolerant, the Jumma people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts in the mountainous south-east region of Bangladesh – which include the large Chakma and Marma tribes – differ ethnically and linguistically from the Bengali majority.

A Chakma mother places her newborn child in a traditional cot called a dhulon, and sings them to sleep with lullabies known as olee daagaanaa.

Today, however, the Jumma children and their parents are almost outnumbered by settlers and brutalized by the military. In one single act of genocide, hundreds of men, women and children were burned alive in their bamboo homes, says Sophie Grig, senior campaigner at Survival International.

© David Brunetti

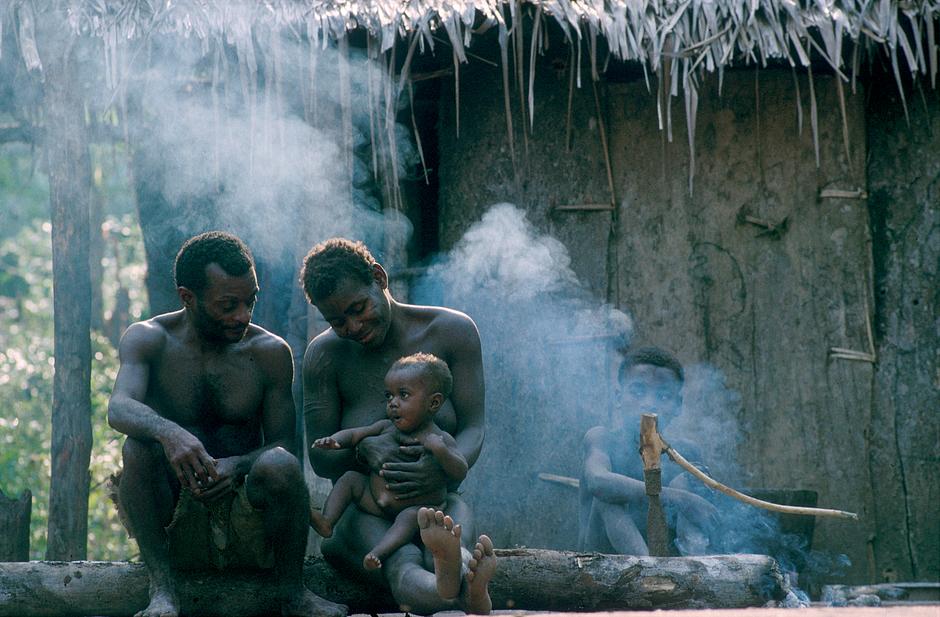

In the marsh forests and riverine valleys of the Congo Basin in Africa, an Aka ‘pygmy’ child plays with his mother.

Ba’Aka infants – like many other tribal babies – are held almost constantly throughout the day.

© Selcen Kucukustel/Atlas

Ba’Aka fathers spend approximately half the day near their babies. They even offer them a nipple to suck if the child is crying, and the mother or another woman is not available.

It is not uncommon to wake in the night and hear a father singing to his child, says Professor Barry Hewlett, an American anthropologist who lived with the Ba’Aka for years.

© Salomé/Survival

In Brazil, mothers of the Awá tribe – one of only two nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes left in the country – have always known equal status with Awá men.

Some Awá women take several husbands, a practice known as polyandry.

Today, the Awá are the most threatened tribe on Earth; over the course of the past four decades, Awá women have witnessed the destruction of their homeland and the murder of their people at the hands of ‘karaí’ – ‘non-Indians’.

© Domenico Pugliese

Awá women breastfeed orphaned monkeys and other baby animals, such as agouti, a South American rodent, in addition to their own infants.

I spend a long time breastfeeding the baby monkeys, an Awá woman called Parakeet told a researcher from Survival International.

And when they have grown, they return to the forest to live. I hear the howler monkey that was once my pet, singing from the trees.

© Survival International

In Malaysia, the Penan have long lived in harmony with their forest and its vast trees, rare orchids and fast-flowing rivers.

The forest is our Mother, they say. It belongs to the countless numbers who are dead, those who are living and the multitudes yet to be born.

© Robin Hanbury-Tenison/Survival

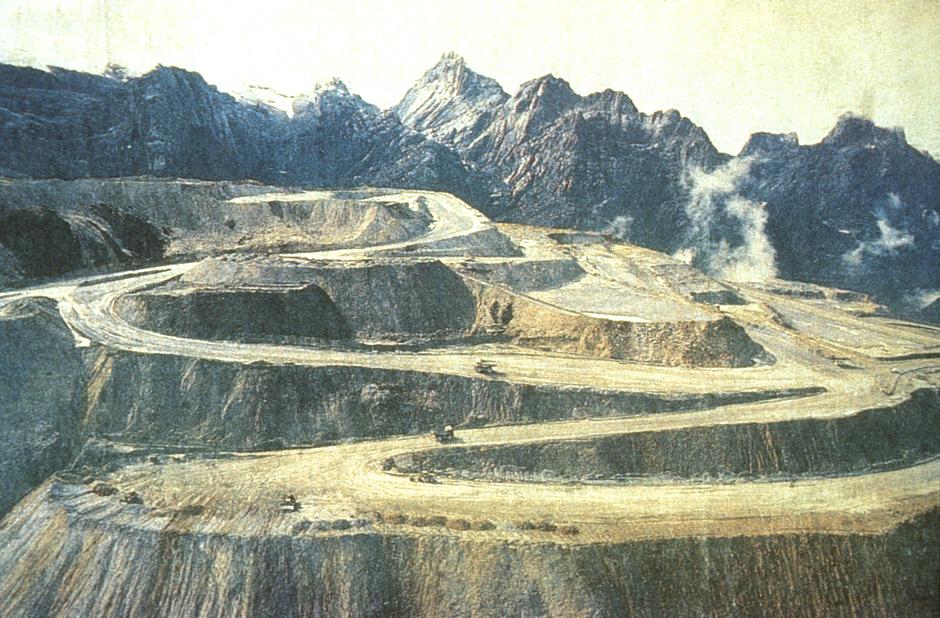

In West Papua, the largest gold and copper mine in the world, operated by the American company Freeport McMoRan, has devastated the land of the highland Amungme tribe, destroying the sacred mountain they know as ‘Mother’.

Many Amungme have been killed by Indonesian soldiers in the process of defending the mine.

The reason why the Amungme people are working really hard to protect their land is because they believe the mountain area is their mother’s head, say the tribe. So now they are gouging out our mother’s brains.

© PaVo/Survival

This Awá mother and her child belong to the most threatened tribe on Earth.

The Awá depend on the rainforest for survival, yet they are suffering from increasing invasions of their land by loggers, ranchers and settlers. Over 30% of one of the Awá’s territories has already been destroyed.

For her, as for other tribal mothers, the solution to her problems lies in the recognition of her fundamental human rights: to self-determination and to the protection of her homeland.

Only then can she and her child be free to live on their own lands, in the way that they choose – free from the threats of oppression, violence and eviction.

If you destroy the forest, you destroy us too, she told a Survival International researcher.

© Survival International

We are not here for ourselves. We are here for our children, and the children of our grandchildren.

Bushman, Botswana.

© Survival International

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...