Peru's uncontacted tribes threatened by gas project

They live no more than 100 kms from Machu Picchu. Today, however, the future of uncontacted tribes who live in the heartland of the ancient Inca Empire is threatened by gas and oil extraction.

It is as the early morning light floods through the walls of Intipunku, the Gate of the Sun, that most walkers gain their first sight of Machu Picchu.

Every year, nearly 1 million tourists visit the Inca citadel. Perched high on a ridge in the eastern Andes overlooking the Urubamba valley, also known as the Sacred Valley of the Incas, Machu Picchu is Peru’s most famous archaeological site; the very heartland of the Inca empire.

Yet few visitors are aware that a mere 100 kms away from its tumbling terraces of stairwells and granite temples live some of the world’s last uncontacted tribes.

Few tourists know that today, these tribes are in danger of extinction.

© Icelight/Wikicommons

The tribes’ ancestral homes are in an area known as the Manú National Park, a region so rich in biodiversity that it was made a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1987.

The park is bordered by the Nahua-Nanti Reserve, where the Nahua, Nanti and members of the Matsigenka tribes live.

The region’s tribal peoples have long known brutal treatment at the hands of invaders seeking to exploit their homeland’s natural resources.

At the end of the 19th century, the area was opened up by the ‘rubber baron’ Carlos Fermin Fitzcarrald, when he crossed the watershed of what is now known as the Isthmus of Fitzcarrald, a land passage which separates the Urubamba and Madre de Dios river basins.

His voracious quest for rubber led to the enslavement and deaths of many Indians.

© Anon/Survival

The Urubamba River is a major tributary of the Amazon River.

During the 1980s, Shell Oil began to search for oil and gas within its valley’s virgin rainforest.

Preliminary explorations included the clearing of paths through previously inaccessible terrain, which were then used by loggers to penetrate the forest.

The loggers brought with them diseases to which the tribes had little or no immunity.

Members of the Nahua tribe, contacted for the first time, succumbed to epidemics of respiratory illnesses: half the community was wiped out in a few months.

Before the loggers arrived, we didn’t know what a cold was, said a Nahua man. The disease killed us. Half our people died. People were dying everywhere, like fish after a stream has been poisoned.

People were left to rot along stream banks, in the woods, in their houses. They were eaten by vultures.

That terrible illness!

© Glenn Shepard (www.ethnoground.blogspot.co.uk)

Shell’s explorations led to the discovery of the Camisea gas fields.

Its vast fields lie in the Lower Urubamba river valley, at the very center of the Nahua-Nanti Reserve, and include two pipelines that cut through the forest to the Pacific coast.

Gas extraction began in 2004. Now operated by a consortium of companies including US’s Hunt Oil of Texas, Spain’s Repsol and Argentina’s Pluspetrol, today Camisea is a project worth $1.6 billion.

© A. Goldstein/Survival

A group of Nahua travelled to Lima in 2003, to warn the government of the dangers of oil and gas concessions to their lands and people.

In the past, Shell worked here and almost all of us died from the diseases, they said. We know that if another company comes here, our rivers and land will be destroyed.

What will we eat when the rivers are dead and the animals have run away? We do not want companies working here.

We want clear water and a peaceful life.

© Johan Wildhagen

Despite the tragedies caused by resource exploration over the past three decades, and the stark warning from the tribes themselves, the Camisea consortium proposed new plans to expand the massive gas project even further into the protected reserve.

Though the enormous risk to uncontacted Indians’ lives has been acknowledged by the gas companies and Peru’s government, the plans have now been approved by Peru’s Culture Ministry, which is charged with protecting indigenous peoples’ rights.

Where will this stop?, said Stephen Corry, Director of Survival International. With this, the government gives the green light for further well drilling, more seismic testing, more helicopters and yet more pollution.

In short, it is again putting the tribes in mortal danger, and potentially allowing history to repeat itself.

© Survival

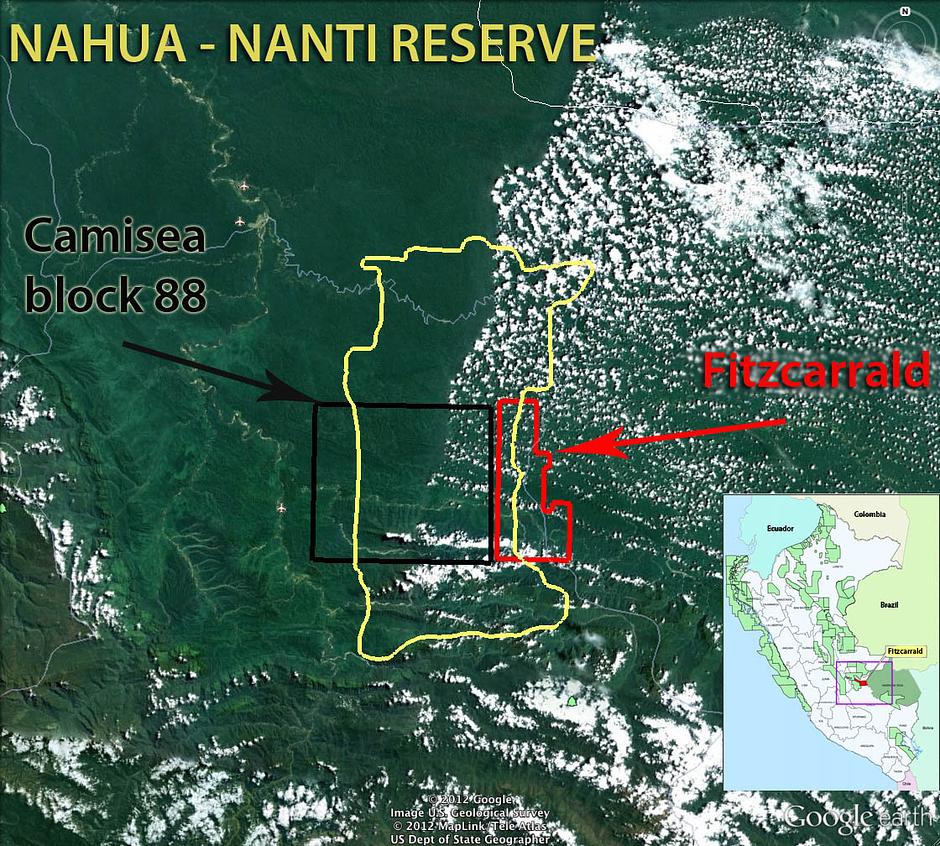

In February 2013, a leaked report revealed secret plans by the Argentine gas giant Pluspetrol to expand operations beyond its current ‘block 88’ into ‘Fitzcarrald.’

Ironically known as Fitzcarrald after the rubber baron, the new site was projected to be east of ‘block 88’. The block would lie in the Isthmus of Fitzcarrald. Its location would cut the Nahua-Nanti Reserve for isolated and uncontacted Indians in half, and put uncontacted tribes’ lives in immediate danger.

Following Survival’s campaign against Fitzcarrald, Pluspetrol released a statement in which it admitted planning what it described as superficial geological studies… for scientific interest, and promised that it would abandon its plans.

© Survival

In May 2012, an unconfirmed report alleged that a number of Matsigenka children had died from gas spill poisoning, and several adults were very ill.

Chaotic development processes have unleashed drastic social and ecological problems, ethnobotanist Glenn Shepard, who has worked with the tribes for years, told Survival recently.

Neither the Peruvian government nor the gas companies can now claim, in good faith, that they have learned from the tragic lessons of the past.

© G Shepard/ Survival

Camisea project’s employees travel to the region by helicopter; its unfamiliar noise drives away the forest game on which the Indians depend.

All the time we hear helicopters, said Jose Choro, a former Nahua leader. Our animals have left, and there are no fish.

AIDESEP, the Peruvian national indigenous organisation, says the Camisea Project is a threat to the physical, cultural, territorial and environmental integrity of indigenous peoples.

© A. Goldstein/Survival

The Nanti are hunters who also grow crops in their gardens.

During the rainforest’s dry season, when water levels are low and white beaches form in the river bends, families camp on the river banks. They take advantage of the low water levels to fish, and unearth buried turtle eggs. Fish are caught using barbasco, a natural fish poison.

Men hunt for game such as tapir, peccary, monkey and deer, walking as much as 15 miles in a day, while women gather wild fruits, palm hearts and beetle larvae.

© Unknown/Survival

Dawn on the upper Manú River, when flocks of green-winged macaws eat from the cliff-side clay licks.

Over generations, the reserve’s tribes have developed an intimate relationship with their forest home and amassed an encyclopaedic knowledge of its flora and fauna.

The Matsigenka are aware of over 300 species of medicinal plants to treat common illnesses, says Glenn Shepard , as well as those for dispelling nightmares, preventing babies from crying at night and improving the skills of hunting dogs.

© Glenn Shephard

The Manú park is also home to uncontacted tribes such as the nomadic Mashco-Piro people.

The Mashco-Piro are almost certainly descendants of the original occupants of the Upper Manu.

Decimated by Fitzcarrald’s attacks, many tribes were forced to abandon agriculture and driven into isolation.

© Jean-Paul Van Belle

Mascho-Piro temporary homes are constructed from palm fronds.

Little is known about uncontacted tribes, but for the fact that they make it clear to the outside world that they wish to be left alone.

At times they react aggressively, as a way of defending their territory, or leave signs in the forest warning outsiders to stay away.

© FENAMAD

These arrows were collected by a Matsigenka school teacher in 2005, after a group of isolated Mashco-Piro showered arrows on him to prevent him from getting any closer.

They are recognizable by their eagle-feather fletchings, wild cane shafts, and unique wrapping of a long coil of Cecropia-fiber twine the length of the arrow shaft.

© G.Shepard/Survival

International law recognizes the Peruvian Indians’ land as theirs, just as it recognizes their right to live on it as they wish.

This law is not being respected by the Peruvian government, nor the companies who are invading the Nahua-Nanti reserve.

These new plans are a clear violation of a 2003 Supreme Decree prohibiting any new development of natural resources inside the Nahua-Nanti Reserve, says Stephen Corry.

© Shinai

The Sacred Valley of the Incas winds its way northwards towards the mountains.

Most Inca cities were destroyed by the Spanish conquest, says Stephen Corry. So it is deeply ironic that while the government ploughs so much time and resources into respecting symbols of its indigenous heritage, it fails to show the same respect to its living indigenous peoples.

Simply put, uncontacted tribes’ lands must be protected or they too will be wiped out, like the Inca Empire was at the hands of the 17th century colonists.

© Cgadbois/Wikicommons

In April 2013, Survival International supporters protested outside Peruvian embassies and consulates around the world to call for an end to the expansion of the Camisea gas project.

The world listened: more than 130,000 signatures have been collected by Survival in protest against Camisea, the UN called for the ‘immediate suspension’ of the expansion, and the Peruvian government has modified the expansion plans to impact less on the Reserve and its indigenous inhabitants.

Yet seismic testing and a flood of hundreds of workers to the region has been approved, and the lives of uncontacted Indians hang in the balance.

Stephen Corry, Director of Survival International, said, Expanding the Camisea project deep into the territory of uncontacted Indians is a reckless and incredibly irresponsible thing to do.

© G Shepard/ Survival

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...