Maasai

Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher have been photographing African tribes for three decades. In a unique gallery collaboration with Survival, Maasai ways of life are beautifully portrayed.

For generations, the Maasai – pastoralist cattle-herders of Kenya and Tanzania – have been semi-nomadic. They have followed the seasonal rains of East Africa, moving their herds from one place to another, so giving the grass a chance to grow again. Their way of life was originally made possible by a communal land tenure system, in which everyone in one area shared access to water and pasture.

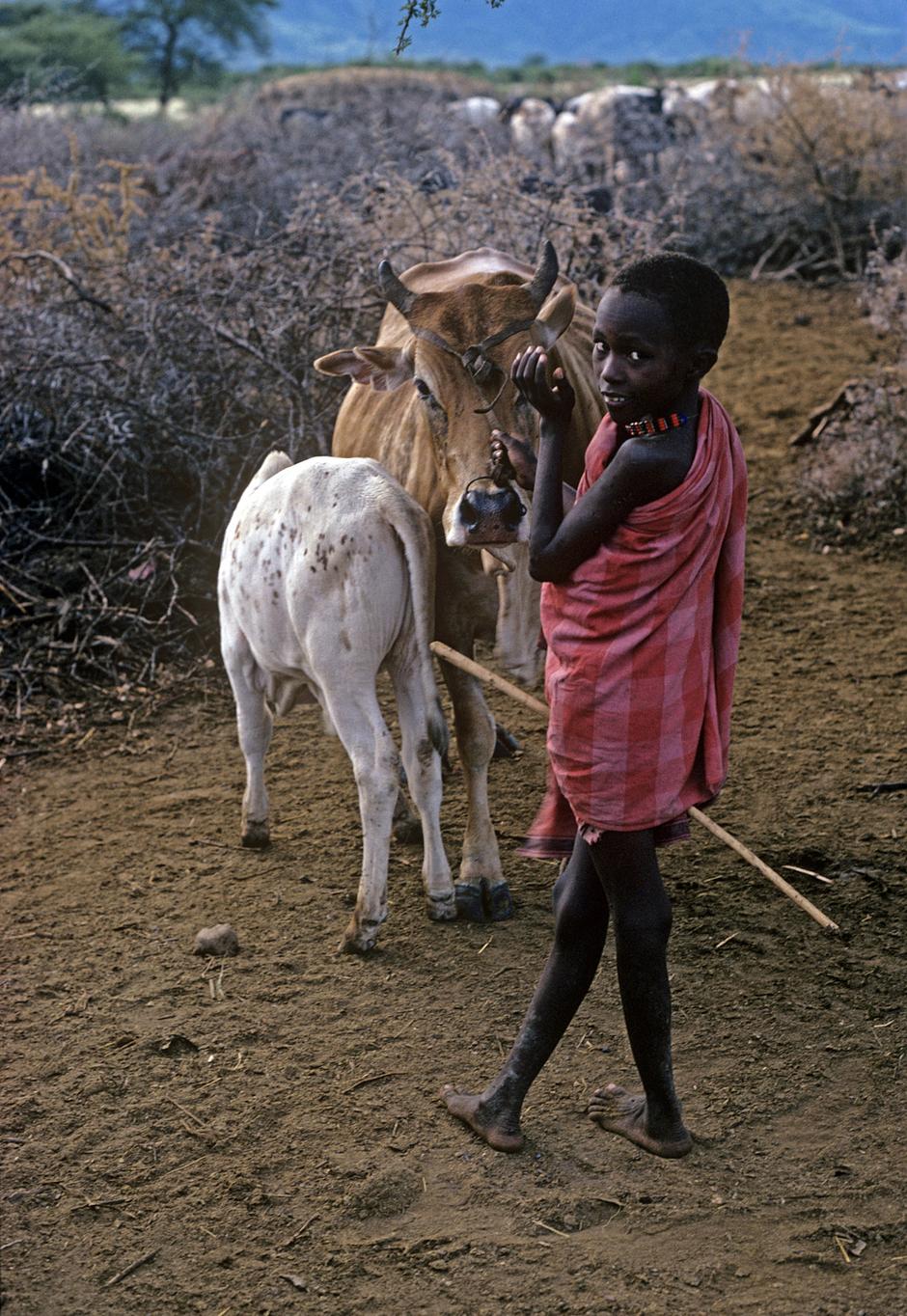

Cattle herds have always been central to their lives. The measure of a man’s wealth is gauged in terms of cattle and children; individuals, families, and clans establish close ties through the giving or exchange of cattle.

The Maasai diet traditionally consisted of raw meat, milk and blood from cattle, but in recent years they have also grown dependent on other foods such as maize, rice, potatoes and cabbage.

Our traditional philosophy is that the land doesn’t belong to any individual: it belongs to the dead, the living, and those not yet born, said Maasai Joseph Ole Simel.

© Beckwith & Fisher

In the 19th century, Maasailand covered most of the Great Rift Valley, from the Laikipia Plateau in northern Kenya to Lake Manyara in north-central Tanzania.

At the end of 19th century, the British constructed a rail road from the coast of Kenya to Lake Victoria, cutting Maasailand in half.

The Maasai were forced to relinquish their fertile volcanic lands and, despite their resistance to European attempts to push them from their territory, were assigned to reserves.

© Joanna Eede

A Maasai boy tends to his livestock wearing a shúkà, the Maa word for a bright-red, ochre-dyed toga that is traditionally worn wrapped around the body.

Many attempts have been made by governments to ‘develop’ the Maasai, based on the notion that they keep too many cattle for the land. Yet the Maasai are efficient livestock producers and rarely have more animals than they need or the land can carry.

We are nomadic pastoralists. If we only get rain once a year and if it rains 50 km away, we need to take our animals there. We need to take our animals to the rivers, said Joseph Ole Simel.

© Beckwith & Fisher

In the second half of the 20th century, a series of parks and reserves were created in Maasailand.

Serengeti National Park was first established in 1940, but it wasn’t until 1959 that the British administration evicted the Maasai, who now retain only the driest and least fertile areas of land.

Several world-famous wildlife reserves and national parks, including Amboseli, Masai Mara, Samburu, Ngorongoro, Manyara and the Serengeti – which takes its name from the Maa word siringit, meaning endless plains – were lands that once belonged to the Maasai.

They have now joined the millions of people – the majority of them indigenous – who have been evicted from their homes in the name of conservation.

Communities are just as badly affected whether they lose their land to conservation projects, or other ‘developments’ such as mines or dams, said Stephen Corry, Director of Survival.

© Beckwith & Fisher

The Maasai live in bomas: several houses arranged in a circular fashion.

The fence around the boma is made from acacia thorns, which prevent lions from attacking the cattle.

© Victor Englebert

A Maasai house, called an inkajijik, is made from branches, mud and dried animal dung. It is very dark inside, which keeps away the flies that swarm around goat and cow herds.

© Beckwith & Fisher

The Maasai have no chiefs, although each village has a Laibon, or spiritual leader.

They worship the god, Engai, and refer to the volcano that rises from the floor of the Great Rift Valley as Ol Doinyo Lengai – the mountain of God.

They say the cooled white lava on its flank is the beard of Engai himself.

© Beckwith & Fisher

Some Maasai today are partly integrated into national society, and take jobs in towns. These include businessmen, politicians and security guards, although many own herds which are kept for them in their home villages.

Stephen Corry said, The Maasai are fiercely proud of their herding way of life and provide a good example of how ways of life very different to the industrialised norm are enjoyed by many people who don’t want to become city-dwellers.

Maasai men and boys see no paradox at all in watching over the cattle herds armed with both spear and mobile phone.

© Beckwith & Fisher

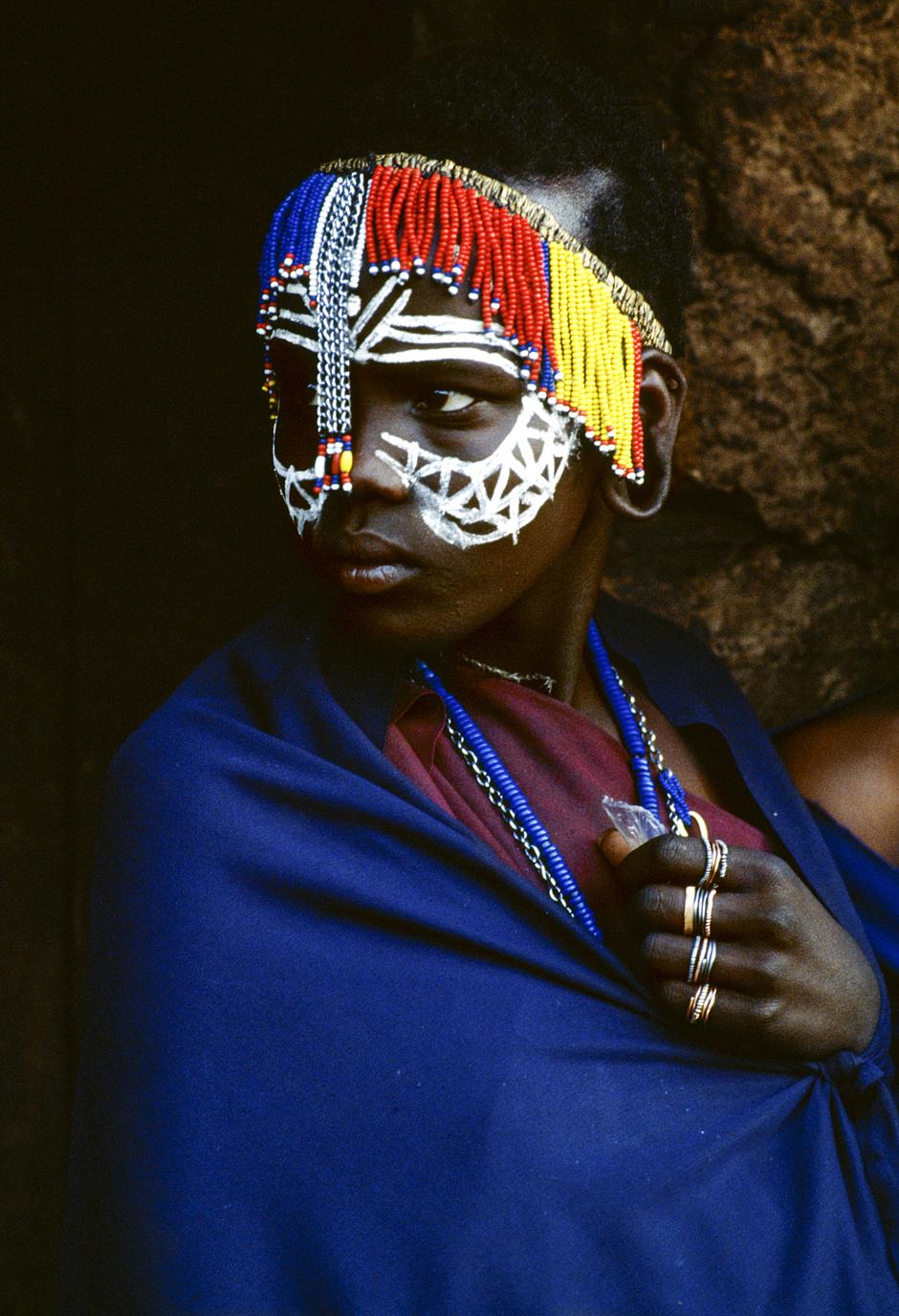

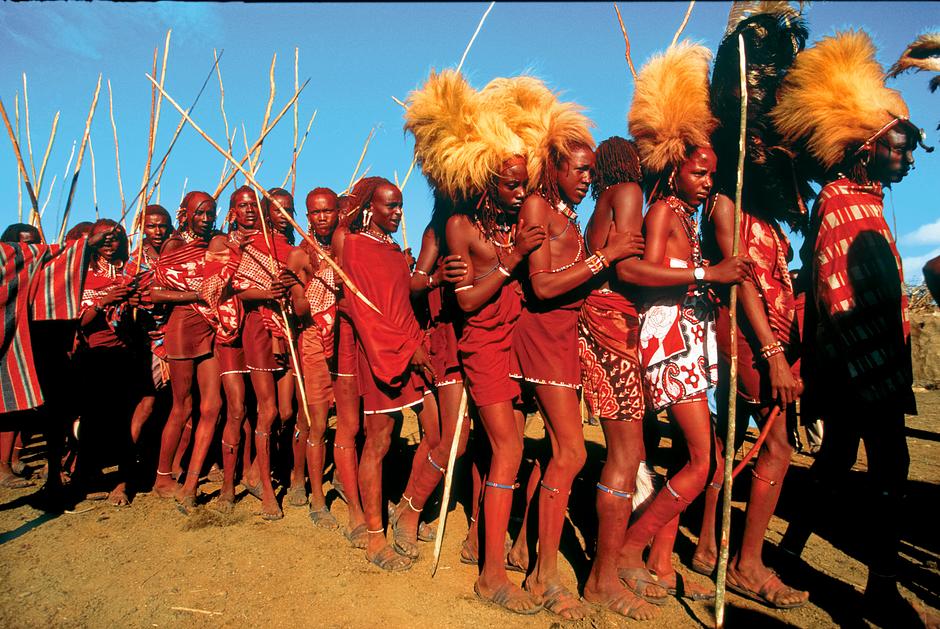

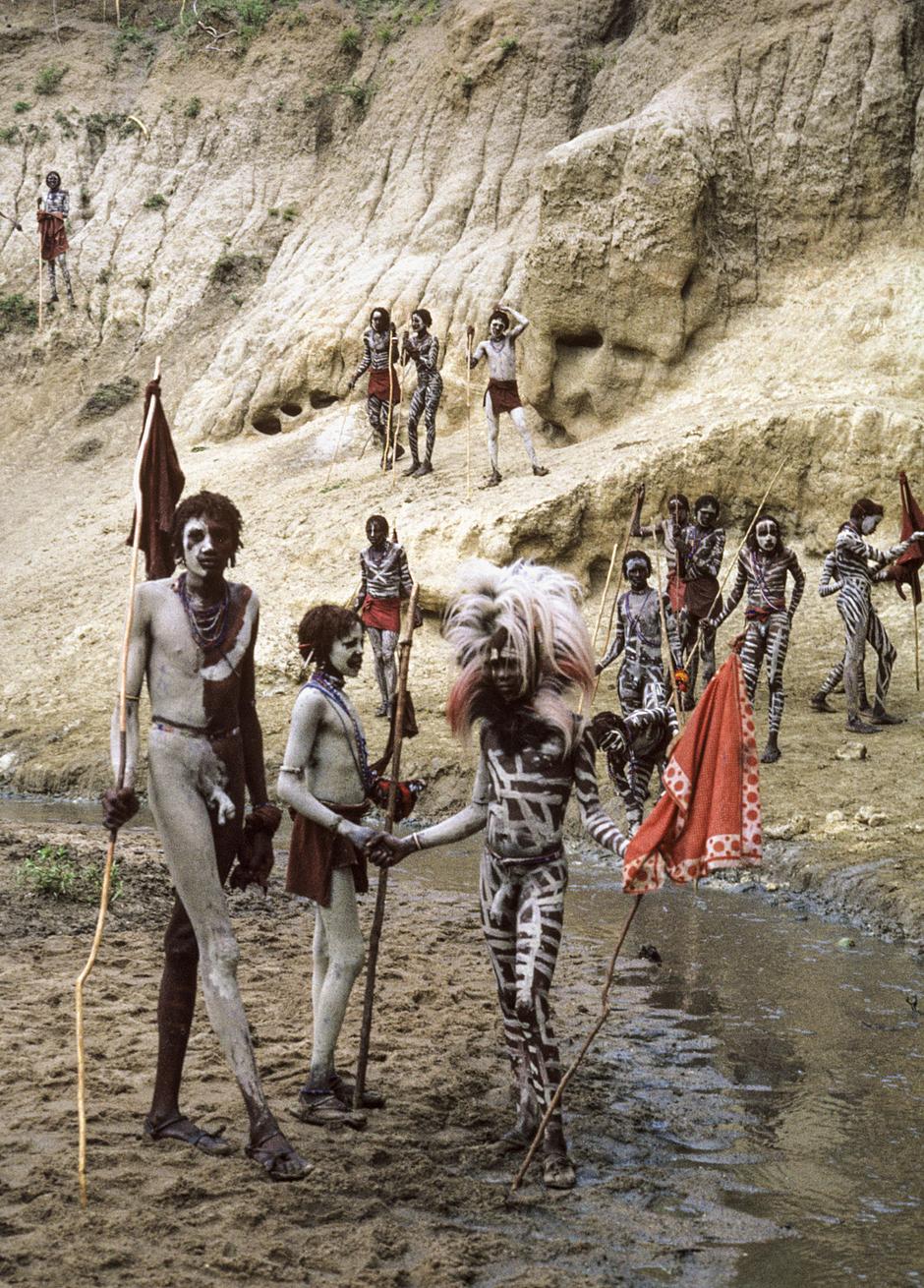

Maasai men and boys are organized into age-sets whose members pass through initiations from youth to ‘warrior’ (moran), and eventually to elders.

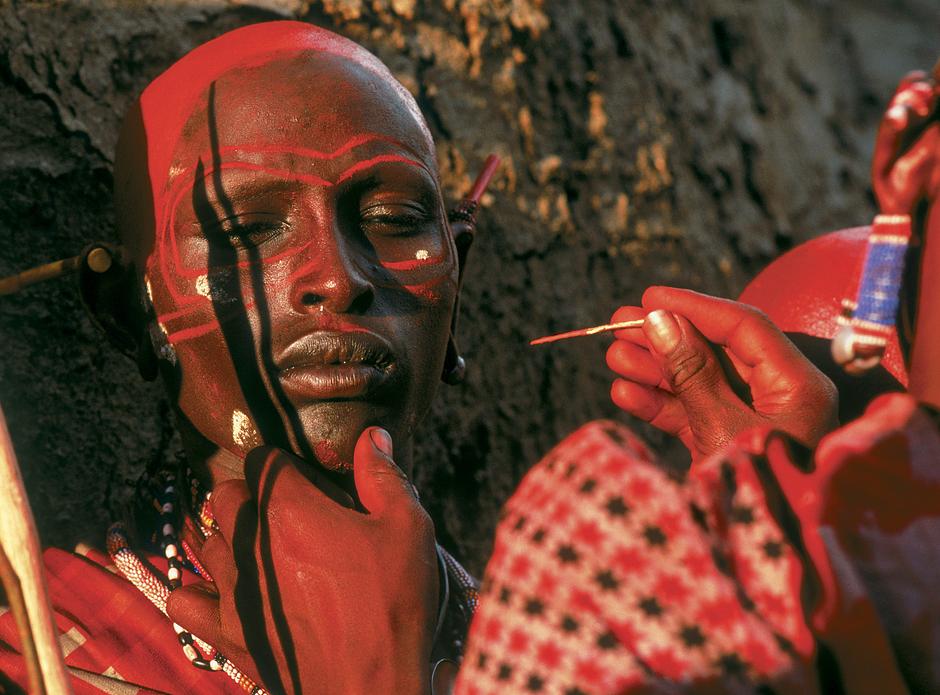

The e unoto ceremony heralds the transition of the teenage moran into manhood. A boy blows into the horn of a greater kudu antelope to summon moran to the start of several days of singing and dancing. In preparation for the climax of the e unoto ceremony, moran paint each other’s faces with ochre pigment.

Moran build their own separate villages, called manyatta, and live according to their own rules, until their age set graduates into married life.

© Beckwith & Fisher

Maasai girls attend the e-unoto ceremony.

© Beckwith & Fisher

Our people are strong, and ready to fight, to oppose this grabbing of our land.

© Beckwith & Fisher

Olduvai Gorge lies in in the Great Rift Valley, Tanzania.

In 1992 the Tanzanian government granted the Ortello Business Corporation (OBC) exclusive safari and hunting rights in an area of Maasailand called Loliondo, in northern Tanzania. OBC is reportedly linked to the United Arab Emirates royal families.

The Maasai had no say in the deal, and a concession was carved out of their land.

Without the land and cattle, there will be no Maasai, said Tepilit ole Saitoti.

Maasailand has also been turned into private farms and government projects.

© Beckwith & Fisher

In 2009, Maasai villages in Loliondo were burnt to the ground and livestock lost when they were removed from the land leased to OBC.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

In a further blow to the Maasai, the Tanzanian government announced in March 2013 a new 1,500 sq km ‘conservation’ area on Maasai lands in Loliondo.

The Maasai would be prevented from travelling to their pasture land in the proposed ‘wildlife corridor’, so destroying their cattle-herding lifestyle; some Maasai believe that it would spell the end of the Maasai as a people, and the Serengeti ecosystem.

However, in September 2013, Tanzania’s President scrapped a plan to take 1,500 square miles from them in the name of conservation.

The area will instead remain with the Maasai, who the President said have taken ‘good care of the area’ since ‘time immemorial’.

© Beckwith & Fisher

Since 1993, Survival has assisted several Maasai groups in their struggle for their lands.

In Kenya, Survival found funds for a programme of consciousness-raising against land sales, and supported the people of Iloodoariak and Mosiro, who were resisting the theft of their land through a legal fraud.

In Tanzania, Survival has backed the demand of the Maasai of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area for a proper say in its administration, and is currently supporting the Loliondo Maasai in their campaign to prevent the take-over of their lands.

© Beckwith & Fisher

Our ancestors led their people beyond their farthest horizons. Their strength and might may be seen in our legends. We must not follow the way of those races of men who have vanished from the surface of the earth.

We have our culture behind us, and our courage, pride and noble truth.

Lemeikoki Ole Ngiyaa.

© Beckwith & Fisher

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...